Back in November of 2011, Sound on Sight contributors were invited to write about their “gateway” films – the movies that first lit them up to the power and magic of cinema. What became apparent to me over the course of that series of posts was how much our respective choices were shaped by who each of us is. It was never as simple as, “Well, then I took Film Appreciation 101 and saw Citizen Kane for the first time…” Nothing’s that simple. Where we were from, how we were raised, the lives we led…all of that and more in some way influenced the choices each of us made. No surprise, that: we view everything – sex, politics, the way the world works – through the prism of our own experience. Why not movies?

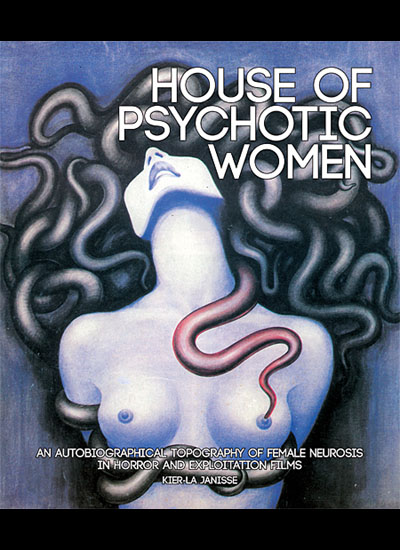

But I’ve never seen the dynamic so clearly at work – or demonstrated so emphatically – as it is in Kier-La Janisse’s House of Psychotic Women: An Autobiographical Topography of Female Neurosis in Horror and Exploitation Films, recently published by FAB Press.

It’s a mouthful of a title, yet even that doesn’t quite capture the boiling stew Janisse has cooked up. Let the book fall open at random, and, depending on the page, House of Psychotic Women (the title comes from the American release of the 1973 Spanish chiller, The Blue Eyes of the Broken Doll) is a deep investigation of women-victimizing grindhouse splatter; another page and Janisse is off on an extended discussion of psychoanalysis, or cultural gender roles, or religion’s place in society; and yet another, and it’s a disturbing memoir of a traumatic upbringing right out of Dickens.

A la the six blind men trying to describe an elephant, House… is not quite any of these; and yet is all of them. It’s neither hybrid nor blend, but a bubbling up of different ingredients surfacing from one page to the next. And the more one learns of Janisse, the more that makes sense.

Janisse, a writer and film programmer as well as the author of A Violent Professional: The Films of Luciano Rossi (FAB, 2007), is an anomaly: a fan of the kind of blood-drenched low-budget flicks which more typically draw in young males, and persistently tick off the feminists with their depictions of women as victims, manipulating victimizers, and brutal avenging angels. To throw a little more gas on the fire, she’s particularly fond of the made-on-the-cheap grindhouse fodder of the 1970s-early 1980s; think flicks like Ms. 45 (1981), Roadside Torture Chamber (1972), and Prey (1977), and imports like The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), and The Blood Spattered Bride (1972).

But it’s not visceral shocks Janisse is interested in (at least not solely). In those movies, she’s found some chord resonant with her own scarred psyche.

Born in 1972 in Winnipeg – “…an isolated city in the dead centre of Canada known for its long, harsh winters and its citizens’ tragic propensity of alcoholism and violent crime” – she suffered through abandonment by her birth parents, a philandering adoptive father and an emotionally abusive stepfather. In the time between her mother’s marriages, Janisse has memories of listening through her bedroom door to her mother being assaulted by an intruder. There’s a parade of foster homes, self-destructive acting out, relationships in which she is sometimes the abused, other times the abuser, an increasingly neurotic and eventually distant mother. She found her own real-life horrors reflected in distorted funhouse mirror fashion in the excesses of a Ms. 45, the fetishistic gore of Italian giallo, and even upscale portrayals of female neuroses/psychoses like What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), and Persona (1966).

To the dissatisfied memoirist or the impatient splatter hound, the book may seem unfocused, unsure of what it wants to be. But House… — like its author – is its own animal, following few rules, going where compulsive curiosity drives it, however tangled that route may be. What holds it all together is Janisse’s powerful pen: “Guilt ran through 1970s genre films like a parasite, eating away at the psyches of female characters, who oscillated between domestic responsibility and the desire for autonomy.” But she never writes more beautifully – or drolly – then when telling her own story:

“…given my erratic emotional and social patterns, my Christian Aunt Pam started to worry about my mental and spiritual well-being. After all, I was a sketchy juvenile delinquent with a gun living in the basement listening to Anarchy in the UK about a hundred times a day. One night…she and her weird friend Beth came down to my room…they were going to save my soul with the help of Jesus Christ. I was really tired and asked if they could save my soul some other time.”

Whether you’re in the camp that considers exploitation movies an undervalued form of subversive, underground cinema, or that it’s gory pandering of the worst kind, what’s clear in House… is the honest connection Janisse makes between her own traumas and grindhouse excesses. Hers is – with a painful, tragic obviousness – a sensibility shaped by the course of her life, related in compelling, insightful, and even, at times, touching fashion..

In the end, that may be the real value of House of Psychotic Women. It’s not about horror and exploitation films, nor is it purely about Kier-La Janisse, but an illustration of just how subjective film criticism is, how non-existent absolute concepts of “good” and “bad” films are, and how the value of what we see is determined not by what’s on the screen, but the personal lens through which we view it. As Janisse writes:

“Everything we see onscreen is a fiction that we are asked to believe, and we believe in it because we can find truth in that fiction.”