Throughout January, SOS writers will be biting the bullet and finally sitting down with a film they feel like bad film buffs for not having seen already.

Directed by Jean-Luc Godard

François Truffaut (story)

Jean-Luc Godard (screenplay)

1960, France

Because of a long-standing allergy to Jean-Luc Godard which erupted after watching Alphaville in some European cinema class (cognate to a generalised mistrust of French ‘classics’ like La règle du jeu, watching which in that same class made me want to chew off the back of the theatre seat out of boredom), I developed a phobia of cinematic ‘waves’, classics, icons (even though I delight in Audrey Hepburn, I only recently summoned the stomach to watch Breakfast at Tiffany’s after taking a hefty dose of anti-‘iconic’ medication) and so steer clear of ‘cult’ works of most kinds. But I reserve the pedestal of loathing for Jean-Luc Godard, of whose oeuvre I generally conceive as that of an over-hyped, misogynist-yet-drooling (let’s film beautiful women as prostitutes! – how original) pretentious hypocrite (oh, La Chinoise, wouldn’t it be great if communism took over the world, please pass the Champagne). So the redeeming trope of French cinema for me has been the “deranged female” paradigm – you know, the crazy beautiful self-destructive type à la Betty in 37.2 le matin, Michèle in Les amants du Pont-Neuf, Angélique in À la folie…pas du tout, and almost any Isabelle Huppert character.

and so steer clear of ‘cult’ works of most kinds. But I reserve the pedestal of loathing for Jean-Luc Godard, of whose oeuvre I generally conceive as that of an over-hyped, misogynist-yet-drooling (let’s film beautiful women as prostitutes! – how original) pretentious hypocrite (oh, La Chinoise, wouldn’t it be great if communism took over the world, please pass the Champagne). So the redeeming trope of French cinema for me has been the “deranged female” paradigm – you know, the crazy beautiful self-destructive type à la Betty in 37.2 le matin, Michèle in Les amants du Pont-Neuf, Angélique in À la folie…pas du tout, and almost any Isabelle Huppert character.

And this is how I never saw À bout de souffle, which, had I paid more attention in class, I would have heard is probably Godard’s most enjoyable, least dogmatic film. Because I did actually find it enjoyable, cheeky, and refreshingly non-didactic.

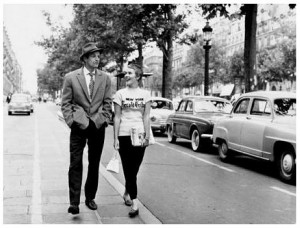

My first memories of Jean-Paul Belmondo, by the way a huge star in Eastern Europe in the 1980s, were of Belmondo the aging-but-still-invincible boxer-pilot-action hero in L’as des as and Le professionnel. Enter Michel Poiccard, the main character in À bout de souffle, whose occupation is a self-professed, all-round asshole. Michel steals cars, pilfers money from his many expendable female auxiliaries, shamelessly lies to them and generally treats them as junk (oh là là, female hitchhikers!, oh non, wait, they are ugly), shoots a policeman point-blank to avoid arrest, and haplessly tries to recover some dosh supposedly owed him by a string of criminal associates, none of which, however, seem to take him seriously. So Michel, the smallest of small-time crooks, spends most of the film trying to scrape together enough dough to buy a newspaper, a sandwich, or to take his love interest Patricia to dinner, etc.

My first memories of Jean-Paul Belmondo, by the way a huge star in Eastern Europe in the 1980s, were of Belmondo the aging-but-still-invincible boxer-pilot-action hero in L’as des as and Le professionnel. Enter Michel Poiccard, the main character in À bout de souffle, whose occupation is a self-professed, all-round asshole. Michel steals cars, pilfers money from his many expendable female auxiliaries, shamelessly lies to them and generally treats them as junk (oh là là, female hitchhikers!, oh non, wait, they are ugly), shoots a policeman point-blank to avoid arrest, and haplessly tries to recover some dosh supposedly owed him by a string of criminal associates, none of which, however, seem to take him seriously. So Michel, the smallest of small-time crooks, spends most of the film trying to scrape together enough dough to buy a newspaper, a sandwich, or to take his love interest Patricia to dinner, etc.

Michel is shamelessly irreverent for the obvious reasons – it’s 1960 and we need to stick up a middle finger at the stodgy bourgeoisie, the establishment, Hollywood, clueless moviegoers, you name it. If you, like me, started out your acquaintance with Belmondo in mediocre fare like L’as des as, you would probably be as dumbfounded as I was by the fact the Jean-Paul Belmondo can act, well, is actually enchanting as the arrogant braggart of a loser that he portrays in À bout de souffle.

The American in question, Jean Seberg’s Patricia, has gained at least as iconic a status as Belmondo’s infantile, neurotic lowlife. At first glance Patricia seems the antithesis of Parisian norms of feminine chic – short hair, trousers, a superficially tomboyish demeanour, but of course tomboyish or independent she is not, and her delicate beauty and impeccable fashion sense are likely part of the enthrallment she exerts on Michel. What she does have is a devil-may-care nonchalance and a lack of anything approaching grown-up preoccupations to match Michel’s. The coquettish, self-involved American may or may not be as slutty as him, but then again it’s the 1960s and everyone sleeps around by zeitgeist default rather than with post sexual-revolution deliberateness. In this respect, the frivolity of the lengthy hotel room sequence between Michel and Patricia is one of the most strikingly modern scenes of the film – presumably unscripted, it must have been a shocker for its naturalistic, intimist, true-to-life depiction of nonsensical bedroom chitchat and for the ambiguity of the relationship between the pair.

Michel’s irreverence is duly matched by the author’s misprise of French institutions – Godard does not miss a chance to deride the moronic police inspectors, the  cackle of pretentions pseudo-intellectuals interviewing a celebrity writer who generously proffers inane opinions of love. More ethically ambiguous from today’s standpoint is the misogynistic drift of Michel’s character. Although in love with Patricia and addicted to her, he has no trouble dispensing the occasional condescending insult at her, while women in general are lousy drivers, never have money, etc. Whether these are Godard’s attitudes as well is uncertain, but the anti-hero’s downfall is precipitated by his faithless beloved. In an abrupt, nihilistic final sequence, the asshole-hero dies an unceremonious, offhand death, the girl is shocked but not especially moved (the anti-misogynist in me feels vindicated alright), while the contempt for any kind of conventional redemptive closure is unnerving yet apt. This same conspicuous flaunting of audience expectations may be what has shoved Godard’s later ideology-dripping oeuvre into an obscure, moralising, nearly-unwatchable, avant-garde ghetto but back when he didn’t try so hard, it worked.

cackle of pretentions pseudo-intellectuals interviewing a celebrity writer who generously proffers inane opinions of love. More ethically ambiguous from today’s standpoint is the misogynistic drift of Michel’s character. Although in love with Patricia and addicted to her, he has no trouble dispensing the occasional condescending insult at her, while women in general are lousy drivers, never have money, etc. Whether these are Godard’s attitudes as well is uncertain, but the anti-hero’s downfall is precipitated by his faithless beloved. In an abrupt, nihilistic final sequence, the asshole-hero dies an unceremonious, offhand death, the girl is shocked but not especially moved (the anti-misogynist in me feels vindicated alright), while the contempt for any kind of conventional redemptive closure is unnerving yet apt. This same conspicuous flaunting of audience expectations may be what has shoved Godard’s later ideology-dripping oeuvre into an obscure, moralising, nearly-unwatchable, avant-garde ghetto but back when he didn’t try so hard, it worked.

Zornitsa Staneva