David Cronenberg’s A Dangerous Method is a fine example of deceptively simple direction, utilizing classic cinematic language in a subtle way so as to direct its audience in a way above and beyond the majority of films of its type. This is probably the director at his technically finest, breezily and classily manipulating the audience through his very planned series of shots.

The film concerns the relationship of Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) and Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen – in what is perhaps his finest role to date). A woman, Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightly – playing, oddly given the film’s standing as period piece, against type) doesn’t necessarily come between them, as much as between their philosophies. Operating around the fringes of the narrative is Otto Gross (Vincent Cassel), a brilliant nymphomaniac, charged by Freud to Jung’s care in the former’s absence.

The first scene in question involves an early, pre-affair meeting between Jung and Sabina. To this point, and for some time following, Cronenberg frequently resorts to very tightly framed 2-shots. This type of simple deep focus (a technique I’ve seen in people from Raul Ruiz to Paul Henreid, and more recently in PBS’s Sherlock), keeps both characters in focus in what appears to either be a composite shot or some kind of shifting lens. In many of these frames – an example is below – if you look to the right edge of the frame you’ll find that the focal fall off is far more dramatic than anywhere else.

SCENE 1

Cronenberg begins this sequence with a less dramatic version of these 2-shots. Sabina sits in front of Jung, her back to him. This is a scene that is all about power – who has it, and who gets it. She is frame right, he frame left. Though she initially dominates the frame by virtue of being larger and closer to the camera, it soon becomes apparent, given the positioning of the characters and his superior placement, that this is initially Jung’s frame.

The sequence continues and again, Cronenberg points us to Jung’s position of superiority. Jung’s initial close-ups are clean, meaning that it is only he in the frame. This isn’t an over-the-shoulder shot. We get none of Sabina’s body in the shot. Psychologically, and often, whoever owns the “clean single” owns the scene.

But perhaps the most telling moments are still to come. When Sabina gets her shot it is either of her back (read: Jung’s POV, his gaze controls), or it’s in 3/4 profile (read: we avoid her eyes full-on and don’t connect with her in the same way as we do Jung).

At a crucial moment, Cronenberg cuts to a ¾ profile close-up of Jung and breaks the 180 line. Notice how Jung is suddenly looking screen left and not right. The eyelines are all askew. The broken line and sudden, jarring angle indicate two things, seemingly at odds with one-another: 1) Jung is about to be bested, where the broken line indicates his loss of control, and 2) Jung is about to find a solution/cure, though it will ultimately lead to his destruction.

The scene is capped by the ultimate shift of power. Cutting back to the 2-shot that began the scene, Cronenberg clearly shows preference by dollying in on Sabina and ending the scene in her closeup, with Jung nowhere to be found. The switch is complete and the foreshadow evident: the patient is leading the doctor.

SCENE 2

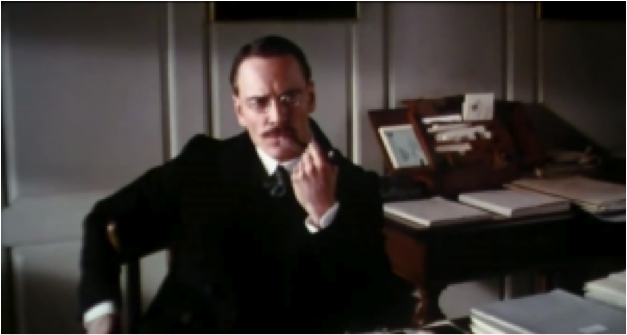

The second scene in question is Otto Gross’ visit to Jung. The two men meet in the latter’s office. What is not yet apparent is that though Jung is charged with curing Otto, it is actually Otto who will more influence Jung. Jung is seated opposite Otto and a first 180 line is established with Jung looking frame right and Otto frame left. Though Jung is framed more centrally, the balance of power is equal.

Otto stands and walks to the back of the room, towards the camera and landing in a close-up. He now dominates the frame, engulfing Jung, who is small in the background. This is the first shift in power, as Otto begins to gain control of the scene.

Otto swiftly walks past Jung and pauses at the bookshelf to Jung’s right, causing a new 180 line to be established. Jung now looks at a harsher angle to the lens and frame left. The more off-angle a character’s eyeline to the camera, the less we identify with them. Note how, in the third shot below, Jung looks far to the side. It’s important, of course, to also note that Jung is still seated to Otto’s standing (dominant position).

Otto again walks around Jung, now establishing a third 180 line. Jung still looks frame left, though he’s turned around and looks a bit closer to the lens. This is Otto bringing him back, and working his way to return to the evenness of the opening shots.

The sequence ends with Otto completing his circle. He has walked a circle around Jung. Confused him in the same way that he will throw Jung’s sexual life into disarray. But at the end, with yet another 180 line – see Jung looking frame right below – the two men are literally at the same level now, as though Jung has talked him down…or as though Otto has or will change Jung’s views.

SCENE 3

The final scene that I want to look at is the simplest in terms of shot selection. The camera appears to be on the water and dollying towards a figure at the dock in the distance, who we soon understand to be Sabina.

A reverse – very Knife in Water – shot places the back of Sabina’s head looming in the foreground, with the boat that is approaching her, the one containing Jung, deep in the background and in relative focus.

Cronenberg cuts back to Sabina from the first dolly, now framing her face in medium-shot, and eventually close-up.

This is followed by a temporal ellipsis where the camera finds them in a high overhead shot, in each other’s arms in the bed of the boat. The camera silently cranes down towards them, framing them more tightly as it approaches.

This sequence is significant again for some delicate shifts in power. The first shot is a point-of-view (POV) – Jung’s. As in the first scene analyzed, this would seem to indicate his gaze, and thus his power. However, the cut to the odd, off-balance framing in shot 2 suggests otherwise. Though this shot still finds us behind Sabina, she clearly looms over him, dwarfing not only Jung, but also the boat that his wife bought for him (the framing is reminiscent not only of Knife in Water, but also of Dustin Hoffman and Anne Bancroft’s early face-offs in The Graduate).

The cut back to shot 1 finds that the POV has been exaggerated: it ends in a close-up that would be impossible for Jung to actually achieve by simply looking at her as his boat moves forward. The close-up in shot 1/3 therefore eliminates the possibility of the male gaze from shot 1 and further allows Sabina to dominate the scene. By closing it as he does, in an equal, balanced frame, Cronenberg tells us that both have achieved their desire, though one (Sabina) manipulated the situation to end as such more than the other (Jung).