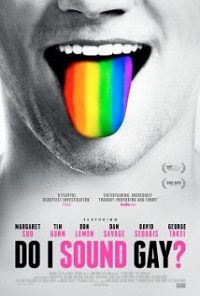

Directed by David Thorpe

USA, 2014

The director (and star) of the new documentary Do I Sound Gay? isn’t comfortable with his voice anymore. Not only does David Thorpe want to jettison his “braying ninny” speech patterns, he wants to deconstruct the ‘gay voice’ and figure out where the hell it comes from. His endlessly-entertaining search takes him to speech therapists, linguists, and veterans of the Gay Rights Movement. This hilarious peek into the gay psyche proves that identity and voice are inseparable, regardless of your sexual orientation.

Thorpe is the perfect guide for such a circuitous journey. He engages with his wit and sarcasm, yet remains completely serious about his inquiry. Coming on the heels of a bad break-up with his lover, 40-something Thorpe is adrift and vulnerable. “I feel out of synch with my voice,” he confesses. In fact, he finds a gay man’s voice to be irritating; a constant reminder that his sexuality both isolates and exposes him, regardless of whether he would wish it.

The question that emerges during Thorpe’s investigation revolves around the nature of identity itself. More specifically, does self-identity determine how we speak, or does speech shape our identity? The answer, admittedly, is far beyond the scope of this modest 77-minute documentary, but it’s a thoroughly entertaining starting point. Psychology, sociology, and snark make for an irresistible combination.

Thorpe enlists the expertise of speech therapists and linguists in his quest to sound more masculine. He works diligently at vocal exercises designed to truncate his singsong mannerisms and be more directive in his communications. When instructed to pronounce the phrase, “How are you?” not as a question, but as a declarative statement, Thorpe is admittedly puzzled. “It sounds like I’m telling them how to feel,” he rightly observes. Interspersed with his training montages are illuminating interviews and delightful film footage of gay luminaries through the ages. It’s a blast to see early television like Liberace and Paul Lynde recognized as the trailblazers that they were.

Also telling are the shifting representations of homosexuals in the movies. From the effete aristocrats of the ‘30s to the mustache-twirling villains of the ‘40s, portrayals of gay men have informed the public’s perceptions, both for good and for ill. Disney, in particular, has featured an alarming number of gay villains in their cartoons over the years, spanning from The Jungle Book to The Lion King. Considering the target demographic for these films were impressionable young children, it’s no surprise that Thorpe and his contemporaries were forever shaped by the negative connotations attached to the distinctive gay voice.

Also telling are the shifting representations of homosexuals in the movies. From the effete aristocrats of the ‘30s to the mustache-twirling villains of the ‘40s, portrayals of gay men have informed the public’s perceptions, both for good and for ill. Disney, in particular, has featured an alarming number of gay villains in their cartoons over the years, spanning from The Jungle Book to The Lion King. Considering the target demographic for these films were impressionable young children, it’s no surprise that Thorpe and his contemporaries were forever shaped by the negative connotations attached to the distinctive gay voice.

Outspoken gay activists such as Dan Savage, David Sedaris, and George Takai all deliver the articulate, hilarious commentary we’ve come to expect from them. Sedaris, in particular, stands out with his warmth and sincerity. Like many gay men, he recalls having a pronounced lisp as a child. His mortified family immediately dispatched him to a speech therapy class; a less-than subtle attempt at re-programming. “Everyone in speech class was gay,” Sedaris muses. “It was like ‘Future Homosexuals of America!”

Numerous experts discuss theories and research surrounding the “micro-variations” in the speech patterns of gay men. Particularly interesting is the concept of ‘covering,’ in which people deliberately alter their voice for a given social setting. This is fascinating not only on a scientific scale, but a cultural one, as well. When you watch the shocking cellphone video of a student being savagely beaten for acting too flamboyantly, it becomes clear why Thorpe and so many kids like him learned to cover all signs of their sexual orientation. At a time when the Supreme Court is making landmark rulings in favor of gay marriage, it’s clear that many people are still confused about their willingness to open the closet door.

There is also confusion within the gay community itself. “Gay men like hyper-masculinity,” admits one interview subject. The result is often the rejection of a voice that sounds too effeminate. Dan Savage brilliantly observes that, “For many gay men, their voice is the last vestige of internalized homophobia.” And yet, many of the men in Thorpe’s film admit to intentionally amplifying their speech and flamboyance to ridiculous levels. Thorpe, in fact, talked like a “normal” heterosexual man until coming out as a college freshman, at which time he deliberately exaggerated the same stereotypically gay mannerisms he once covered from his High School classmates.

There is also confusion within the gay community itself. “Gay men like hyper-masculinity,” admits one interview subject. The result is often the rejection of a voice that sounds too effeminate. Dan Savage brilliantly observes that, “For many gay men, their voice is the last vestige of internalized homophobia.” And yet, many of the men in Thorpe’s film admit to intentionally amplifying their speech and flamboyance to ridiculous levels. Thorpe, in fact, talked like a “normal” heterosexual man until coming out as a college freshman, at which time he deliberately exaggerated the same stereotypically gay mannerisms he once covered from his High School classmates.

Ultimately, Do I Sound Gay? is a modest documentary that still manages to raise some thought-provoking questions. Each answer seems rooted in a complex mixture of genes and environment. Nature may indeed make you gay, but society may refuse to nurture those instincts. Voice becomes an important proclamation of self-acceptance, both to the outside world and to the empowered speaker. Thorpe’s cursory research might not win him any academic honors, but it speaks volumes about the human condition. Do I Sound Gay? is not only an entertaining film, it also provides valuable encouragement for those struggling to find their own voice.