Critic Richard Combs, in a 1994 Film Comment piece on Siegel, wrote that whatever the milieu, Siegel’s strongest movies – The Big Steal (1949),  Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954), Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Lineup (1957), Hell Is for Heroes, The Killers (1964), Madigan (1968), Coogan’s Bluff (1968), The Beguiled, Dirty Harry, Charley Varrick, Escape from Alcatraz (1979) – all shared the traits of “…strong characters, tightly contained situations, and a narrative style that is…both direct and oblique, objective and frenzied, casually realistic and coolly abstract.”

Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954), Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Lineup (1957), Hell Is for Heroes, The Killers (1964), Madigan (1968), Coogan’s Bluff (1968), The Beguiled, Dirty Harry, Charley Varrick, Escape from Alcatraz (1979) – all shared the traits of “…strong characters, tightly contained situations, and a narrative style that is…both direct and oblique, objective and frenzied, casually realistic and coolly abstract.”

The plots in Siegel’s best films are remarkably simple: The Big Steal is one, long chase; Hell Is for Heroes is a basic Us vs. Them punch/counterpunch combat story; in The Beguiled, wounded Union soldier Clint Eastwood tries to sweet-talk the mistress of an all-girls school from surrendering him to Confederate troops; Dirty Harry stalks a serial killer; a handful of cons plot an Escape from Alcatraz in what is, essentially, a prison breakout procedural. The A-B-C simplicity of Siegel’s plots grants him ample running room for complexity of character, inter-character relationships, and, that most subtle – and hard-to-define – aspect of cinema, tone. Siegel carries all this off with a clean, unobtrusive, yet flavorful visual style, and with both a logistical and dramatic economy which would be one of the most oft-cited earmarks of his work, making him, at his commercial peak from the late 1960s through the 1970s, something of a master of the mid-range thriller.

Even during this flush period he still had his missteps: the surprisingly bland espionage thriller Telefon (1977, which Siegel took over from original director Peter Hyams), the problem-plagued Rough Cut (1980, Siegel was one of the movie’s four directors), and still another troubled production, the aptly titled Jinxed (1982). Still, in his better, more personally imprinted work, he typically outclassed those working on a more lavish scale.

Even during this flush period he still had his missteps: the surprisingly bland espionage thriller Telefon (1977, which Siegel took over from original director Peter Hyams), the problem-plagued Rough Cut (1980, Siegel was one of the movie’s four directors), and still another troubled production, the aptly titled Jinxed (1982). Still, in his better, more personally imprinted work, he typically outclassed those working on a more lavish scale.

Siegel’s characteristic economy traces back to the very start of his career in the 1940s at Warner Bros. where he wound up unofficial head of the studio’s Montage Department. He benefited from moviemaking advice and counsel from directors like Anatole Litvak (City for Conquest , 1940; Sorry, Wrong Number, 1948) – for whose features Siegel cut trailers – and especially from conferring with his opposite number at MGM, montage master Slavko Vorkapich. Under such guiding hands, Siegel served a form of directorial apprenticeship assembling sometimes complex scripts for his montage sequences, and came to believe early on in the unlimited possibilities of a succinct form of visually-driven storytelling. He left Warners after earning his feature director’s stripes on the Victorian-era thriller The Verdict and the drama Night Unto Night (1949), then spent better than a decade gypsying around the B-movie circuit and occasionally foraying into television.

As early as The Big Steal – only his third feature – Siegel showed a visual assurance, logistical expertise, a storytelling precision, and a penchant for the unpredictable twist in the seemingly

predictable which he would carry forward throughout his career. The story (screenplay by Drayson Gerald Adams and Daniel Mainwaring, adapted from Richard Wormser’s story, “The Road to Carmichael’s”) concerns a GI on the run (Robert Mitchum) trying to clear himself of a false robbery charge who hooks up with an at-first dubious Jane Greer on an extended chase along the back roads of Mexico, a setting neatly conforming to the movie’s modest budget without betraying it. Faced with a familiar story he feared might become a standard-issue B-thriller, Siegel opted to infuse the movie with a genre-contrary sense of humor, turning Steal into one of the few (possibly only) comic noirs. In the process, the central characters are flipped from their usual genre stances: Mitchum’s hero thinks of himself as a self-assured, smart cookie, but he’s actually rather dim, the clever thinking getting him through one tight spot after another coming from Greer — a character who, in many noirs, would typically have been relegated to tag-along romantic interest. The Mexican police colonel (played by one-time matinee idol Ramon Navarro), rather than fulfilling the then prevalent below-the-border stereotype of slow-witted, comic and corrupt Mexican cop is, instead, shrewd, observant, intelligent, and scrupulously honest. The Military Policeman (William Bendix) so doggedly hunting Mitchum turns out – in a final twist – to be the unknown true culprit Mitchum has been frantically searching for.

Siegel would thereafter be regularly attracted to characters who refuted expectations (a gangland kingpin played by tweedy Vaughn Taylor in a wheelchair in The Lineup; Mob banker Woodrow Parfrey worried about how a recent robbery threatens his community standing), heroes who were not always likable (a brutalizing Clint Eastwood in Dirty Harry; Steve McQueen’s killing machine of a GI in Hell Is for Heroes; the inquisitive hitmen of The Killers) or even particularly heroic (Walter Matthau’s fast-thinking, double-dealing bank robber in Charley Varrick). Siegel put a peace sign belt buckle on Andy Robinson’s serial killer in Dirty Harry confessing he didn’t quite understand the significance of doing so himself, but liked the idea of this cold-blooded killer’s blindness to the truth about himself.

Siegel would thereafter be regularly attracted to characters who refuted expectations (a gangland kingpin played by tweedy Vaughn Taylor in a wheelchair in The Lineup; Mob banker Woodrow Parfrey worried about how a recent robbery threatens his community standing), heroes who were not always likable (a brutalizing Clint Eastwood in Dirty Harry; Steve McQueen’s killing machine of a GI in Hell Is for Heroes; the inquisitive hitmen of The Killers) or even particularly heroic (Walter Matthau’s fast-thinking, double-dealing bank robber in Charley Varrick). Siegel put a peace sign belt buckle on Andy Robinson’s serial killer in Dirty Harry confessing he didn’t quite understand the significance of doing so himself, but liked the idea of this cold-blooded killer’s blindness to the truth about himself.

Though some of Siegel’s Bs suffered from expected constraints – tight budgets, second-rate casting, inferior scripts – he regularly showed, as he did with Steal, that with the right script and able (if B-list) talent, he could turn out exemplary work: Riot in Cell Block 11, with its prisoners and warders both depicted as victims of a flawed penal system, remains discomforting and relevant today; Invasion of the Body Snatchers, shot on a skimpy $250,000, stands as one of the all-time science fiction classics.

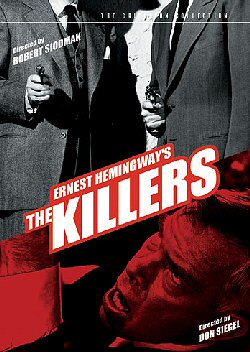

Toward the end of the 1950s, with feature jobs harder to come by in an economically suffering Hollywood, Siegel turned more often to TV of which – with its even more threadbare budgets and fleeting shooting schedules – he thought little, declaring it “…equal to the worst ‘B’ pictures that one can make.” He thought even less of his own work for the medium, saying his only inspiration for taking TV jobs were the paychecks. Dismissive as Siegel was, the vitality of his TV work still managed to stand apart from an endemic blandness in the medium. If for nothing else, Siegel’s work in TV is worth remembering for one particular project, a TV movie which, despite the strangling limitations of TV production and Siegel’s own self-deprecation, was, even at the time, taken as an extraordinary piece of filmmaking: The Killers.

Adapted by Gene L. Coon from a slip of an Ernest Hemingway short story and intended as the medium’s first made-for-TV movie, elements of The Killers haven’t aged well. The movie can’t shed a TV “look” burdened, as it is, with the stale quality of the studio back lot and back-projection traveling scenes. Too, what seemed provocative in 1964 – the awkwardly choreographed slow-motion assassination which opens the movie – seems positively tepid next to the more graphic and elaborately orchestrated violence of the big-screen movies which shortly followed i.e. Point Blank (1967), Bonnie and Clyde (1967), The Dirty Dozen (1967), The Wild Bunch (1969). Still, thematically, the movie remains a powerful extrapolation of noir existentialism and nihilism: there are no heroes, only Bad Guys; there is an enveloping sense of inevitable, all-encompassing tragedy; and the movie ends with the destruction/self-destruction of every principal character.

Lee Marvin and a fey Clu Gulager play two hitmen hired by an unknown party to kill trade school instructor John Cassavetes. Marvin is intrigued by the acquiescence with which Cassavetes had given himself over to his executioners. “There’s only one guy who’s not afraid to die,” Marvin calculates, “that’s a guy who’s already dead.” Marvin and Gulager learn Cassavetes was a washed-up auto racer who’d been the getaway driver in an armored car robbery. As much as for the money, Cassavetes’ reason for taking on the job was his interest in coquettish Angie Dickinson, the moll of gang leader Ronald Reagan (in his last movie role). Now further enticed by the still-missing robbery loot, Marvin and Gulager discover Dickinson had played both Cassavetes and Reagan to her own advantage; a betrayal which left Cassavetes emotionally gutted and ready for death. In a pitch-perfect noir finale, a mortally wounded Marvin faces off with Dickinson who is, once again, trying to bargain and tease her way clear. The dying Marvin looks at her over the sights of his raised pistol, rebuffs her with, “Lady, I haven’t got the time,” and pulls the trigger. He picks up the money-stuffed valise, staggers outside as the sound of police sirens near, finally collapses from his wounds, the money spilling free into the street.

Lee Marvin and a fey Clu Gulager play two hitmen hired by an unknown party to kill trade school instructor John Cassavetes. Marvin is intrigued by the acquiescence with which Cassavetes had given himself over to his executioners. “There’s only one guy who’s not afraid to die,” Marvin calculates, “that’s a guy who’s already dead.” Marvin and Gulager learn Cassavetes was a washed-up auto racer who’d been the getaway driver in an armored car robbery. As much as for the money, Cassavetes’ reason for taking on the job was his interest in coquettish Angie Dickinson, the moll of gang leader Ronald Reagan (in his last movie role). Now further enticed by the still-missing robbery loot, Marvin and Gulager discover Dickinson had played both Cassavetes and Reagan to her own advantage; a betrayal which left Cassavetes emotionally gutted and ready for death. In a pitch-perfect noir finale, a mortally wounded Marvin faces off with Dickinson who is, once again, trying to bargain and tease her way clear. The dying Marvin looks at her over the sights of his raised pistol, rebuffs her with, “Lady, I haven’t got the time,” and pulls the trigger. He picks up the money-stuffed valise, staggers outside as the sound of police sirens near, finally collapses from his wounds, the money spilling free into the street.

Put off by the movie’s dark themes as much as by its (for the time) brutal violence, network sponsors rejected The Killers, and Universal – which had produced the movie – put it into theatrical release. The Killers represents the beginning of a fruitful relationship between Siegel and Universal, and was the first in a series of big screen crime thrillers (Madigan, Coogan’s Bluff, and – on loan-out to Warner Bros. – Dirty Harry, his first major hit) which finally upraised Siegel from the B-list.

The richness of Siegel’s later work stems from the same skilled craftsman’s precision exercised in his early films. His casts, both in early and later years, are generally small (The Big Steal rests on the shoulders of four main characters; Dirty Harry is primarily carried by six roles; Escape from Alcatraz by about the same), but the movies nevertheless feel character-rich. Siegel favored stories which – despite having a main “anchor” character – played closer to ensemble pieces, his supporting players working with clearly defined, individualized roles giving his stories a sense of being fully populated.

Similarly, his movies “feel” bigger in scope than they really are: on The Verdict, Siegel concealed the physical limits of his Victorian street set by having the studio fog machines produce enough mist  to conceal the 1946 skyline just beyond; in Dirty Harry, he conveyed the air of a citywide dragnet looking for a rooftop sniper with only a roving shot from a patrolling helicopter taking in a handful of police-uniformed extras scattered about city roofs. Riot in Cell Block 11, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Beguiled, Charley Varrick, and especially Escape from Alcatraz are all stories which, like The Big Steal, organically demand very little in terms of locations and production design. Most of The Big Steal takes place on back roads; the bulk of Escape from Alcatraz plays out on a handful of locations all within the Alcatraz prison; The Beguiled remains mostly within the walls of an all-girls school; Charley Varrick is an urbane robbery thriller uniquely set against the sparse milieu of rural New Mexico.

to conceal the 1946 skyline just beyond; in Dirty Harry, he conveyed the air of a citywide dragnet looking for a rooftop sniper with only a roving shot from a patrolling helicopter taking in a handful of police-uniformed extras scattered about city roofs. Riot in Cell Block 11, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Beguiled, Charley Varrick, and especially Escape from Alcatraz are all stories which, like The Big Steal, organically demand very little in terms of locations and production design. Most of The Big Steal takes place on back roads; the bulk of Escape from Alcatraz plays out on a handful of locations all within the Alcatraz prison; The Beguiled remains mostly within the walls of an all-girls school; Charley Varrick is an urbane robbery thriller uniquely set against the sparse milieu of rural New Mexico.

His imparting of dramatic information is equally spot-on, often minimalistic, and it is sometimes surprising – in light of how full-bodied his stories feel – to discover how brief the running times are on his most memorable movies: Invasion of the Body Snatchers clocks in at a brisk80 minutes; The Lineup at86; Hell Is for Heroes, 90; Madigan, 101; Coogan’s Bluff, 100; Dirty Harry, 102. Yet there is nothing in the storytelling which feels underwritten or anemic.

Siegel obviously approved of Steve McQueen’s cutting down a script monologue in Hell Is for Heroes to a single, exasperated, right-on-the-money line – “How the hell do I know?” – following an ill-fated McQueen-led attack on an enemy pillbox. Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry gains a sudden pathos with one line referring to his late wife as he explains how she was killed in an automobile accident: “There was no reason for it, really.” In the same movie, after a D.A. informs Eastwood serial killer Andy Robinson is to be released from custody on a technicality, and then skeptically asks Eastwood why he is so sure Robinson will kill again, Eastwood sends a chill through the audience replying simply, “Because he likes it.” In Charley Varrick, we find out the connection between bank robber Walter Matthau and his dead female getaway driver when – showing little outward emotion – he gives her corpse a farewell kiss, then removes her wedding ring and slips it on a finger next to his own.

Siegel obviously approved of Steve McQueen’s cutting down a script monologue in Hell Is for Heroes to a single, exasperated, right-on-the-money line – “How the hell do I know?” – following an ill-fated McQueen-led attack on an enemy pillbox. Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry gains a sudden pathos with one line referring to his late wife as he explains how she was killed in an automobile accident: “There was no reason for it, really.” In the same movie, after a D.A. informs Eastwood serial killer Andy Robinson is to be released from custody on a technicality, and then skeptically asks Eastwood why he is so sure Robinson will kill again, Eastwood sends a chill through the audience replying simply, “Because he likes it.” In Charley Varrick, we find out the connection between bank robber Walter Matthau and his dead female getaway driver when – showing little outward emotion – he gives her corpse a farewell kiss, then removes her wedding ring and slips it on a finger next to his own.

The acme of Siegel’s terseness is Escape from Alcatraz. According to Siegel, during development of the piece, Paramount executives were put off by the lack of character exposition in the script (by Richard Tuggle from S. Campbell Bruce’s novel). They suggested the audience needed to know the full back-story on Clint Eastwood’s character, an explanation of why he’d turned professional criminal. Siegel’s response was the more the character was explained, the “…less real he becomes. The trick is to suggest…” So, in Escape, when a fellow convict asks Eastwood what kind of childhood he had, the reply is a curt, “Short.” In another scene from Escape, convict Paul Benjamin – a “lifer” – is called to the visitor’s gallery. He sits across the glass from a young woman (Candace Bowen) he does not recognize. She picks up the phone, says the single word, “Daddy…,” and Benjamin hangs up the phone and walks away.

Siegel was not as ostentatiously visual a director as some of his 1950s confreres, like, say, Robert Aldrich, but he had a feel for just the right  non-distracting visual accent. Shooting Invasion of the Body Snatchers on location in the small town of Sierra Madre grounded his fantastic story in a recognizably real-world milieu; he gained a similar edge shooting Riot in Cell Block 11 in Folsom Prison using actual guards and prisoners as extras; his use of the still under construction Los Angeles freeway system for the finale of The Lineup is a textbook example of making an action sequence more visually engrossing without simply piling on the careening and crashing of cars; and he similarly enhanced the climactic foot chase of Dirty Harry by running his protagonists through a quarry; also in The Lineup, he has Eli Wallach’s increasingly desperate hood trying to enlist sympathy from the wheelchair-bound senior gangster known only as The Man (Vaughn Taylor), the latter shot in extreme close-up as an emotionless, silent monolith in a meeting on a roller rink mezzanine; there’s the lapse into a dreamy slow motion shot of a Confederate cavalry patrol passing by in The Beguiled as Clint Eastwood’s hiding wounded Union soldier secures the silence of a schoolgirl with a seductive kiss.

non-distracting visual accent. Shooting Invasion of the Body Snatchers on location in the small town of Sierra Madre grounded his fantastic story in a recognizably real-world milieu; he gained a similar edge shooting Riot in Cell Block 11 in Folsom Prison using actual guards and prisoners as extras; his use of the still under construction Los Angeles freeway system for the finale of The Lineup is a textbook example of making an action sequence more visually engrossing without simply piling on the careening and crashing of cars; and he similarly enhanced the climactic foot chase of Dirty Harry by running his protagonists through a quarry; also in The Lineup, he has Eli Wallach’s increasingly desperate hood trying to enlist sympathy from the wheelchair-bound senior gangster known only as The Man (Vaughn Taylor), the latter shot in extreme close-up as an emotionless, silent monolith in a meeting on a roller rink mezzanine; there’s the lapse into a dreamy slow motion shot of a Confederate cavalry patrol passing by in The Beguiled as Clint Eastwood’s hiding wounded Union soldier secures the silence of a schoolgirl with a seductive kiss.

Siegel may have been at his stylistic best in Dirty Harry, getting impressive visual mileage – along with cinematographer Bruce Surtees – from San Francisco’s unique jigsaw topography, giving the hunt for a rooftop sniper the sense of a high-rise three-dimensional chess game. There’s a brutal nighttime face-off with the killer below the massive cement cross in Mt. Davidson Park; the mournful, wordless exhumation of the raped and brutalized body of a teenaged girl in pre-dawn hues at Golden Gate Park; Eastwood’s torturing of killer Andy Robinson under the glaring field lights of an empty Kezar Stadium, the sequence climaxing with a helicopter shot soaring further and further back into the night until the stadium lights become a dim, diffused glow lost in the San Francisco fog; the final foot chase through a cacophonous quarry plant ending in abruptly contrasting quietude by a nearby stagnant pond.

Like John Sturges (The Magnificent Seven, 1960; The Great Escape, 1963), Siegel’s movies are often thought of as more action-heavy than they actually are. Siegel himself once – wrongly – described Dirty Harry as “wall-to-wall” action although there’s only 10-15 minutes of action spread out through the movie’s 102 minute running time. He despised excess and gratuitous violence, and violent acts in his movies tend to be limited to abrupt, short-lived bursts. Siegel’s application of action is as sparing and precise as his application of exposition and character revelations. The architecture of his best movies is typically one of long – even languid – stretches jarred by sudden, brief, emotionally intense spasms of action. Siegel uses those long lulls to let his movies breathe; to cultivate a sense of place, and to allow his characters to show their other dimensions, to fill his movies with a full-bodied life rather than meaningless kinesis.

Madigan, for example, opens with an under-the-credit sequence taking the viewer through a cop’s tour of duty on nighttime Manhattan; Charley Varrick also begins with a montage sequence, this one a more pastoral portrait of a small New Mexico town stirring to life on a quiet, sunny morning. In Dirty Harry, Eastwood, tracked by Bruce Surtees’ camera, slowly walks the roof of a high rise which was the source of a fatal sniper shot, San Francisco laid out below him, its jumbled buildings spilling out toward the bay – the future game board for the cop/sniper contest to come.

Despite his reputation for taut suspense, there are often throwaway scenes and bits of business in a Siegel movie which do little – or nothing – to advance the main plot, but do fill in Siegel’s canvas by deepening his central characters, and/or bringing supporting characters and the background atmosphere to life: a pasture-side conversation between Mob banker John Vernon and his tweedy minion Woodrow Parfrey in Charley Varrick as they exchange woes brought on by the robbery of the Mafia money drop they administer (Vernon looking out at the pasture: “I never thought I’d want to trade places with a cow”); Paul Benjamin’s heartache at meeting with the daughter he’s never known in Escape from Alcatraz; a foiled suicide attempt in Dirty Harry.

Even within his action sequences, Siegel would step back and pause, refusing to let rampant action swallow the emotion of the moment. Best example: Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry Callahan is disturbed from his lunch counter hot dogs by a bank robbery. There follows a short, explosive exchange of shots with the robbers lasting about 25 seconds. One of the robbers lies wounded and is about to receive the movie’s signature, “Did I fire six shots or only five?” speech from Eastwood. But, between the last shot fired and the beginning of Eastwood’s speech, Siegel gives Eastwood a slow 33-second walk across the debris-littered street.

If Siegel knew how to ease off an action sequence to let his characters breathe, conversely, he knew how to ever-so-slightly jack up the tension in what could be a simple, perfunctory scene. In Charley Varrick, Matthau’s bank robber meets with shady gun shop owner Tom Tully to get a line on someone who can supply him with a false passport. As Matthau turns to leave and Tully asks if there’s anything else he can help with, Matthau turns back to ask about the possibility of fencing money. Lalo Shifrin’s quiet but urgent score slips in underneath, and the dialogue lapses into a cagey argot. Tully asks how much money is at stake: “A lot? Or a whole lot?” “A whole lot,” Matthau replies, and the stakes of the exchange suddenly multiply.

Siegel’s thrillers – particularly his best 1960s/1970s works – are as deserving of attention as more grandiose and artistically ambitious works of the time like The Godfather (1972), Mean Streets  (1973), The Wild Bunch, The French Connection (1971), Bonnie and Clyde, etc. While younger, more self-consciously “arty” directors like Coppola, Friedkin, and others self-destructed almost as soon as they had risen to prominence, Siegel – in his 50s and 60s – with a balanced blend of efficient craftsmanship, professionalism, and creative insight, was turning out his best work. He confessed to little overt artistic ambition, claiming to be surprised at the fuss stirred up by a movie he’d intended as simple entertainment (i.e. Dirty Harry). Yet, in his unassuming way, he managed to produce a number of philosophically provocative classics, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Hell Is for Heroes, and The Killers among them.

(1973), The Wild Bunch, The French Connection (1971), Bonnie and Clyde, etc. While younger, more self-consciously “arty” directors like Coppola, Friedkin, and others self-destructed almost as soon as they had risen to prominence, Siegel – in his 50s and 60s – with a balanced blend of efficient craftsmanship, professionalism, and creative insight, was turning out his best work. He confessed to little overt artistic ambition, claiming to be surprised at the fuss stirred up by a movie he’d intended as simple entertainment (i.e. Dirty Harry). Yet, in his unassuming way, he managed to produce a number of philosophically provocative classics, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Hell Is for Heroes, and The Killers among them.

Siegel did not overturn or invert classic forms, he broke little new ground. Rather, he worked within the traditional frameworks of war story, crime thriller, and so on, tweaking their recipes just enough to make them feel new and novel. In the process, he turned out a string of classic thrillers through the master craftsman’s process of telling a story as well as it could be told.

– Bill Mesce