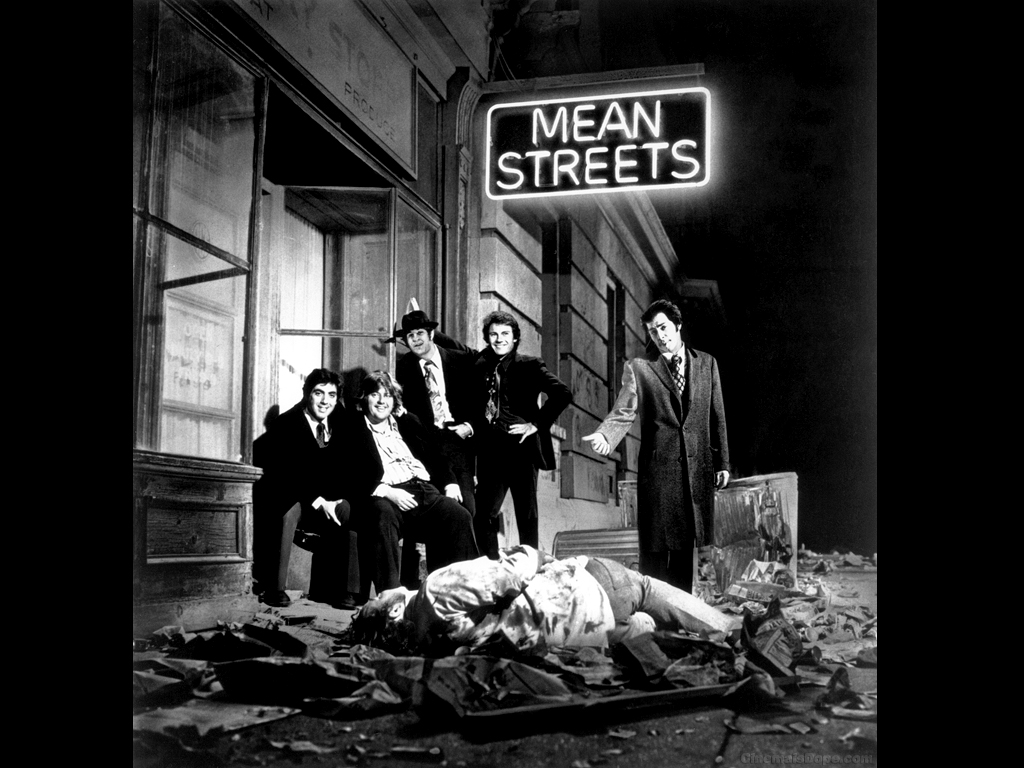

We love crime movies. We may go on and on about Scorsese’s ability to incorporate Italian neo-realism techniques into Mean Streets (1973), the place of John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950) in the canon of postwar noir, The Godfather (1972) as a socio-cultural commentary on the distortion of the ideals of the American dream blah blah blah, yadda yadda yadda…but that ain’t it.

We love crime movies because we love watching a guy who doesn’t have to behave, who doesn’t have to – nor care to – put a choker on his id and can let his darkest, most visceral impulses run wild. Some smart-mouth gopher tells hood Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci), “Go fuck yourself,” in Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990), and does Tommy roll with it? Does he spit back, “Fuck me? Nah, fuck you!” Does he go home and tell his mother?

Nope.

He pulls a .45 cannon out from under his jacket and empties it into the kid. C’mon, be honest: some jackass cuts you off on the highway, somebody runs over your foot in the supermarket with their cart and doesn’t even say, “Sorry,” somebody steals your yogurt out of the office fridge, are you going to look me in the eye and say that somewhere way down in some deep, dark, highly societally-repressed part of you – the barbaric part buried under millennia of that increasingly complex and organizing thing we call civilization – wouldn’t want to pop the guy?

Heist flicks gain a special affection. When we’re talking about The Big Job, The Big Heist, The Big Caper, The Big Score, we’re not talking about hoods, strong-arms, goons, stick-up men, smash-and-grabbers, kick-in-the-door-and-yell-“Grab-some-sky” types; we’re talking about artists.

The thief – the good thief, the expert thief – actually looks to avoid violence. He’s relying on brains and skill rather than muscle and guns, and there’s something about that to respect, even for the law-abiding, comfortably repressed good citizen. You have to admire the imagination of the job, the timing, the expertise.

And of course, there’s the lure of the money, too. It’s the rare person sitting in the seats who isn’t tantalized by the money; a big bucket of it scored in one, fell swoop. A suitcase full of green opens up on the screen, a case full of gleaming bullion, a satchel upends and glittering diamonds spill out onto a tabletop like stars in a black velvet sky…don’t you – at least sometimes – turn to your movie mate, and share a grin that says, “Imagine.”

Smarts, skill, nobody gets hurt (if you’re lucky), and walking out saddled with a dream’s worth of loot. That’s why we like a good heist flick.

The devoted cineastes know the classics: the noirs like The Asphalt Jungle, or expatriate Jules Dassin’s French-made Rififi (1955), its half-hour heist sequence daringly shot in total silence; the Anglophiles might talk about the charming black comic capers that were part of the great parade of Ealing comedies in the 1950s, flicks like The Ladykillers (1955), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), and Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949); the more cosmopolitan types will fondly remember the hysterical Italian-made Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958), and Dassin’s frothy Turkish caper, Topkapi (1964), as light as his Rififi was dark.

If you prefer your thievery with a more contemporary taste, you’ve got a rich buffet to choose from as well. Like your heist flicks light and easy going down? Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Eleven (2001), Twelve (2004), and Thirteen (2007) mix Topkapi-like fun with a heavy swirl of The Big Con a la The Sting (1973) for more laughs than thrills. Like your capers dark and hard? You can’t do better than modern day crime flick master Michael Mann and Thief (1981) and/or Heat (1995). Unless you want to go for Ben Affleck’s The Town (2010).

But, as with any genre, there are the lesser-knowns, the cult flicks, the unjustly forgotten. Not to remember them and, by the grace of Netflix, not to give them a look…that would be a crime:

****

1: Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974). Written and directed by Michael Cimino.

1: Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974). Written and directed by Michael Cimino.

The descriptives one usually associates with heist flicks are “suspenseful,” “gripping,” “nerve-wracking,” and the like. What you usually don’t here are, “affecting,” “touching,” “moving,” but those are the words that come to mind watching Michael Cimino’s directorial debut, a heist flick unique in structure, feel, and look.

Clint Eastwood plays a con on the run from the gang that mistakenly thinks he double-crossed them on a previous job who hooks up with amoral drifter Jeff Bridges. Both rootless, drifting somewhere between something and nothing, the laconic Eastwood and hyper Bridges (in an Oscar-nominated Support Actor performance) become friends. They later partner up with two members of Eastwood’s old gang – thuggish George Kennedy and frog-eyed Geoffrey Lewis – to redo an earlier depository robbery which involves blasting through the vault door with a 20 mm cannon.

Unlike most heist flicks, the robbery is not the heart of the story. T&L’s first act, played in an easy pace against the rolling hills of Montana, has more in common with such odd couple flicks as Midnight Cowboy (1969) and Scarecrow (1973) than with hard-edged crime thrillers, and that, paradoxically, is what invests you in the caper. This is the rare crime flick where you care. The memorable moments from T&L are not from the job, but the small moments that bring Cimino’s characters to life-sized life: the crappy jobs they take to raise their stake money, Lewis and Kennedy crammed in the small cab of an ice cream scooter, Kennedy’s paunchy con gasping through a punch-up with Eastwood as his asthma kicks in.

All of that makes the movie’s melancholy epilogue all that more moving. Thunderbolt & Lightfoot ends not with giddy triumph (Soderbergh’s Oceans flicks) or even ironic defeat (The Asphalt Jungle), but with a true sense of loss, and gives Eastwood one of his finest moments.

Best moment: Lewis and Kennedy pull over to a kid on a suburban street with their ice cream scooter. When the kid mouths off about how a competing ice cream wagon has product, Kennedy snarls, “Hey, Kid: go fuck a duck!”

As lean and taut as Thunderbolt & Lightfoot is amiably ambling, Varrick is one of the oft-underappreciated Siegel’s best. Walter Matthua is Charley Varrick, a one-time stunt flyer turned crop duster who indulges in the occasional small-time bank robbery with his wife and two accomplices to get by. But their latest caper goes wrong, and Varrick’s wife and one of his gang are killed. Worse, the innocuous bank they knock over turns out to be a Mafia drop. While Matthau’s remaining partner (Andy Robinson) thinks of this as a lottery win, Matthau realizes they are in deep doo-doo: “I’d rather have ten FBIs after me.”

The clever caper here is not the straightforward bank robbery, but Matthau’s trying to figure out a way to navigate between the belligerent Robinson, the cops, and sadistic Mafia hit man Joe Don Baker to find an out.

It’s a movie of small, clever moves (you may have to go back and re-watch the movie to figure out how Varrick throws each of the players at each other and arranges his own eventual disappearance), precisely etched performances, a gallery of indelible characters, and the kind of hardboiled dialogue that Matthau and company deliver done to a turn (“How much money we talking about?” asks one of Matthau’s contacts when he asks about fencing off his loot. “A lot?” “A whole lot,” says Matthau. “Hot?” “Burning up.”).

Favorite moment: Mob money exec John Vernon meets with his underling, banker Woodrow Parfrey, by a pasture to talk about the suspicious shadow cast over them by their Mafia bosses. It’s a great pas de deux of acting, shot almost entirely in a single take. At one point in the conversation, Vernon looks out at the pasture, and says to Parfrey, “Check out the brown one. Man, what a set of jugs.”

3: The Thomas Crown Affair (1968). Directed by Norman Jewison. Written by Alan Trustman.

3: The Thomas Crown Affair (1968). Directed by Norman Jewison. Written by Alan Trustman.

Crown is probably better-remembered for the 1999 remake with Pierce Brosnan and Rene Russo than for the original with Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway, and that’s a shame, because as much fun as the remake is – and it is – it doesn’t have the soulfulness of the original.

Self-made millionaire Tommy Crown (McQueen at his coolest) doesn’t have a second act for his life. A success at everything but his marriage, he’s faced with no worlds left to conquer, the only challenge left to him, so he tells a girlfriend, being “Who am I going to be tomorrow?”

His answer is to plan a bank robbery which leaves him pitted against equally sharp and clever and self-made insurance investigator Dunaway. Their duel of wits escalates/evolves into erotic feint-and-parry and from there into a love affair, but one always dogged by the question of how each will play the final hand.

The remake is a lighter piece about one of those too-clever-for-real-life heists and a happy, neatly-wrapped ending. But the original came out at a time when Hollywood happy endings not only seemed phony, but offensively so when it seemed there were no real-life happy endings to be had. The most delicious moment in the movie is its teasingly ambiguous ending which leaves the questions, Did McQueen’s Crown ever really love Dunaway? Or was it just another challenge to stave off suffocating ennui? Or maybe was it a little bit of both?

With a great look from Haskell Wexler, one of the all-time cinematographic greats, and sharply cut by future director Hal Ashby (the chess scene between McQueen and Dunaway is classic), and a haunting score by Michel Legrand, the original tends to leave the remake looking like petty theft.

4: The War Wagon (1967). Directed by Burt Kennedy. Written by Clair Huffaker from his novel.

4: The War Wagon (1967). Directed by Burt Kennedy. Written by Clair Huffaker from his novel.

“It’s a Western!”

“No, it’s a heist flick!”

“No, it’s a Western!”

“It’s two, two, two movies in one!”

And so it is.

By the mid-1960s, John Wayne was well-ensconced as, well, John Wayne. He’d become that rarities of rarities among actors: a brand name. All the public had to know was John Wayne, cowboy hat and a horse, and they knew what they were going to get. Thankfully, on a regular basis, a director and a script would come along that seemed to know how to get the most out of such a popular commodity. The War Wagon was one of them.

Wayne plays an ex-con who unfairly did time after nasty ol’ Bruce Cabot framed him then stole Wayne’s rather nice ranch and the profitable gold mine therein. Wayne’s revenge plan involves knocking over one of the regular shipments of gold out of the ranch made on the horse-drawn armored car known as the War Wagon. He teams up with womanizing hired gun Kirk Douglas for whom Wayne is a sore spot (“You caused me a lot of embarrassment. You’re the only man I shot that I didn’t kill.”), drunken demolition man Robert Walker, Indian tribal liaison Howard Keel, and bellicose inside man Keenan Wynn.

There’s nothing novel in a motley group coming together for a big score, but Huffaker’s script is heavily and delightfully laced with a droll wit that keeps the movie a fun watch throughout.

Example: two of Cabot’s men draw on Wayne and Douglas which – as one might expect – leaves the two overreachers dead in the dusty street. Douglas, with the kind of smirk only Douglas could pull off, says, “Mine hit the ground first.” To which Wayne drawls back as only the Duke could, “Mine was taller.”

5: Gambit (1966). Directed by Ronald Neame. Written by Jack Davies, Alvin Sergeant, Sidney Carroll.

5: Gambit (1966). Directed by Ronald Neame. Written by Jack Davies, Alvin Sergeant, Sidney Carroll.

Jules Dassin’s Topkapi kicked off a wave of similarly buoyant, light-hearted caper flicks set amid exotic settings, movies like How to Steal a Million (1966), Hot Millions (1966), After the Fox (1966), and Duffy (1968), to name a few. For my money, the best of the lot is Gambit, starring a still-a-star-on-the-rise Michael Caine with an equally ascendant Shirley MacLaine.

Caine is – as we come to find out – a wannabe master thief who has concocted with his partner (John Abbot) an elaborate charade to gain them entry to the private art collection of jillionaire Herbert Lom. The object of Caine’s maneuverings: an invaluable ancient Chinese statue which Lom also values for its resemblance to his deceased wife…who bears a striking resemblance to the bubbly Hong Kong dancer Caine’s persuades into baiting Lom’s interest.

This one is just about fun, with a great cast with both Caine and MacLaine showing why they became stars, Lom as a heavy with a heart, and Neame and his writers laying out some bait of their own with an early-film tease showing how the caper is supposed to work which only barely matches the climactic heist.

Stay to the very end and the last, final twist, and ask yourself: is Caine turning good? Or does he know?

6: Heist (2001). Written and directed by David Mamet.

6: Heist (2001). Written and directed by David Mamet.

You can’t just watch a Mamet movie; you have to listen to it as well. Mamet plays with words in a WTF fashion the way a juggler keeps a chainsaw, an apple, and a bowling ball in the air at once: remarkably. Example: says one of the movie’s bad guys: “Everybody needs money. That’s why they call it money.”

Gene Hackman is a master thief arm-twisted into a big caper by double-dealing Danny DeVito. Hackman only agrees once he figures out how to put this heist through a few pretzel twists to both protect his ass and insure that this time around he comes out ahead.

As he proved with House of Games (1987) and The Spanish Prisoner (1997), Mamet knows how to put together a twisty-turny plot so convoluted it makes The Sting look as complicated as The Cat in the Hat, and it helps that he’s got a deep-bench of a cast who know how to dish up those aural ballets of Mametesque dialogue: Hackman, DeVito, Delroy Lindo, Sam Rockwell, Mamet favorites Ricky Jay and Rebecca Pidgeon (Mrs. Mamet).

My favorite moment: after a climactic shootout, Hackman, gun in hand, stands over the wounded DeVito who has given him so much trouble. DeVito, looking to buy himself a few more seconds on this earth, gasps out, “Don’t you want to hear my last words?” Says Hackman just before he pulls the trigger, “I just did.”

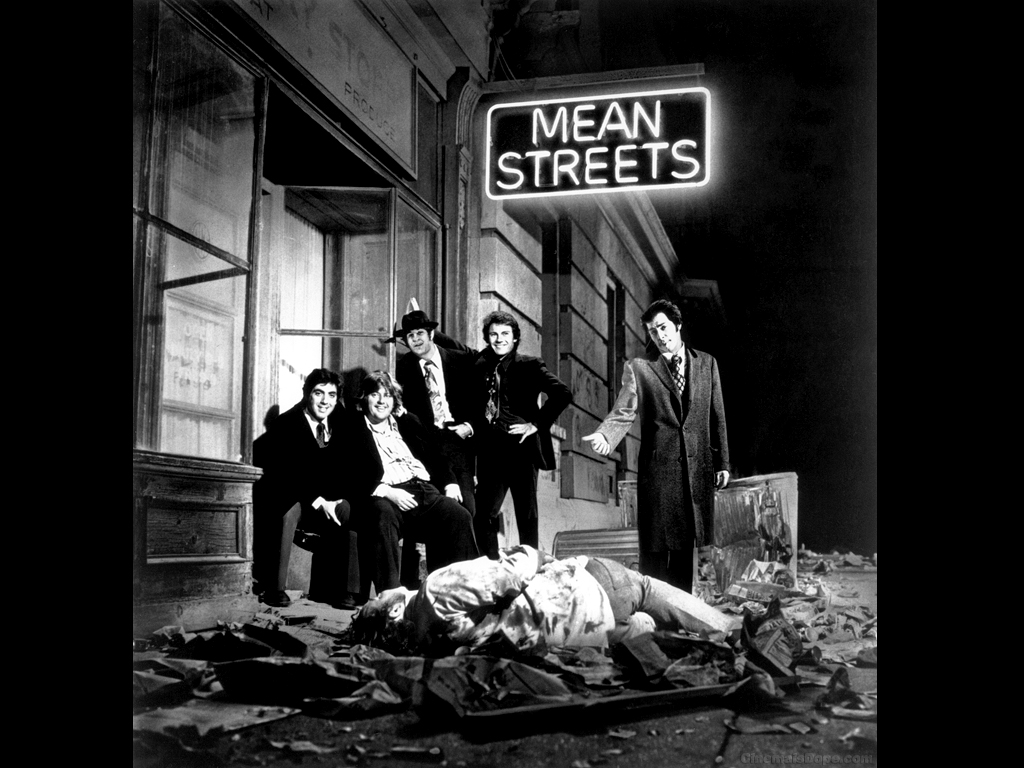

7: The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984). Directed by Stuart Rosenberg. Written by Vincent Patrick from his novel.

7: The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984). Directed by Stuart Rosenberg. Written by Vincent Patrick from his novel.

At the time, there were those who wrote Pope off as a Mean Streets wannabe, and it’s not hard to see where they were coming from. Mickey Rourke plays the Harvey Keitel part, a guy with an honorable if self-destructive commitment to look out for his impulsive, hot-headed cousin (Eric Roberts pushing a little too hard to be Robert DeNiro), each hustling to fulfill a dream: maitre d’ Rourke wants ( like Keitel in Streets) a restaurant of his own one day, and Roberts, well, he just wants to be the guy that can plunk down the money to sit ringside at a Sinatra concert.

But when Roberts’ finagling of checks at the restaurant where they both work lands them out on the street, Roberts comes up with a caper to put them both where they want to be. They enlist an aging locksmith/ex-con (the great character actor Kenneth McMillan) to crack a safe supposedly holding a boatload of bucks. But along with the money, they find the safe is holding a stash of tapes made by a crooked cop of brutal local Mob boss, Bed Bug Eddie. With a psycho like The Bed Bug, simply giving the money back isn’t going to be enough to get the trio out from under.

If Pope suffered, at the time, from comparison to Scorsese’s then recent classic, time has been good to the movie. Free of Scorsese’s shadow, it’s a fun bit of New York grit, flavorful, giving us a Mickey Rourke who was still a star-in-the-making at the time (and making us wonder what the hell happened), backed by an ensemble of top-notch character actors besides McMillan including M. Emmet Walsh, Jack Kehoe, Philip Bosco, Tony Musante, and, utterly chilling as the animalistic Bed Bug Eddie, Burt Young.

Be forewarned: The Happening isn’t for everybody. Frankly, I’m not sure who it is for. But it’s still worth a watch as a heist flick trying to go someplace heist flicks don’t usually go.

Faye Dunaway, Robert Walker, and Michael Parks are a bunch of 60s-style flower kids drifting from one eventful time-killer to another who fall in with too-cool-for-school George Maharis and then fumble their way into kidnapping Mafiosi Anthony Quinn. The problem is, nobody wants to pay Quinn’s ransom: not his wife, not his Mob colleagues, not even his mother. To them, Quinn’s not coming back is actually the more attractive option. Quinn takes command of his own kidnapping to get revenge on those who cut him loose.

But The Happening is after more than just a triple-reverse take on a kidnapping tale. It strains – and it does often seem like a strain – to be after something more. Trying to plug into the late 1960s sense of disillusionment and disappointment, the movie flounders its way toward some sort of climactic existential finale without quite pulling it off.

Look, what was hip in 1967 seems corny now (actually, the movie’s interpretation of 1967 hip was a bit corny then), and what at first seems a fun premise goes off the rails in its grab for substance, but it’s worth watching – once – to see something truly (if not totally successfully) different in the genre. And in a genre with a rather limited menu – you either get away with it or you don’t – different is a noble aspiration.

– Bill Mesce