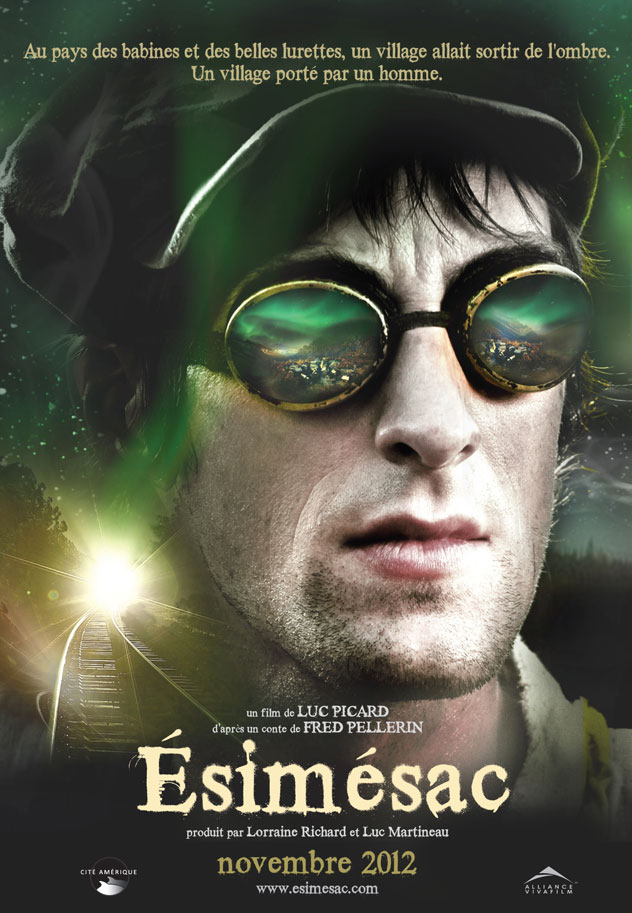

Directed by Luc Picard

Written by Fred Pellerin

Canada, 2012

The holidays will soon be upon us, which naturally means that, when switching channels on the tele at home, some will inevitably stumble on some holidays movie classics, such as Rudolph, the Red Nosed Reindeer and A Christmas Carol. Most of these are happy affairs, or, at the very least, ones that conclude happily. New holiday themed pictures arrive on a consistent basis, and while are cut from a similar cloth as the rest in that they lean on the chirpy, lighter side of things. It is always interesting when filmmakers tread a different path, shaking things up a bit. Sure, Silent Night, Deadly Night is one such example, although that movie is not exactly very good. Although it shall most likely not be categorized strictly as a holiday film given that the entire first half of the story occurs earlier in the calendar year, Ésimésac tries for a different, more solemn vibe for its story, depicting an un-habitual version of Christmas for a very unfortunate little town in Québec, Saint-Élie-de-Caxton, where resides the film’s screenwriter and famous Québec raconteur, Fred Pellerin.

Fred Pellerin has been winning the hearts and minds of Québec for some years already with his unique storytelling sensibilities. There is a lot of whimsy to his tales, meaning that they are not always the most realistic. This is important for Luc Picard’s film, Ésimésac, which is set in the province’s countryside some decades ago, presumably during WWII considering that one character, the town’s blacksmith Riopel (Gildor Roy) is producing tools of warfare while his daughter, Lurette (Maude Laurendeau) bemoans the absence of her husband, off to war. In this section of the world, the laws of physics and human physiology do not apply in the same way they do in the real world. Ésimésac (Nicola-Frank Vachon), the titular character and protagonist of the piece, is 25 years of age, but only left his mother’s womb two years ago. Another particularity is that the grandeur of an individual’s shadow determines the size of that same person’s ego. Ésimésac has none, and as such is the most selfless person in town, always working to help others. His devotion to helping the townsfolk like his little sister Marie (Sophie Nélisse) and shopkeeper Toussaint (Luc Picard) with the communal garden project is put into jeopardy when Riopel encourages him to help out with the construction of a new railroad which will presumably have a train stop at their village, thus giving a lift to its ailing, pitiful economy. Will his new job cause him to have an ego and what impact might that have on those who loved him so?

Ésimésac is a very curious film, not the least of which because it comes from the mind of Fred Pellerin, who has become something of an indie culture darling in Québec. His is not known for developing screenplays but rather short stories that speak to the human spirit and are layered in deep coats of cuteness and whimsy. Those characteristics bleed into the rest of the film from top to bottom. For that reason, one’s appreciation of the picture will greatly depend on how much magical, touchy feely material one can digest. Curiously enough, a lot of that is part of the dialogue, less so the visual makeup of the world director Picard and writer Pellerin present audiences. On that latter point alone, the film mostly feels like it is grounded in some sense of reality, save perhaps for the presence of a witch (Isabel Richer) that appears at about the midway point of the story and some other, more miner set design touches that remind the viewer this is not quite the real world, like a huge boulder which has a smoothly carved slide on one side the children use for amusement. The world building, from both an aesthetic and script standpoint, is not very difficult to follow yet provides enough imagination and off-kilter elements to create the impression that indeed something a bit different, somewhat novel is unfolding on screen, which is always a welcomed factor considering how frequently contemporary films are blamed for doing just the opposite.

The film has also been extremely well cast, and not only because of relative newcomer Nicolas-Frank Vachon’s respectable performance in the lead role, who does bring a sense of honesty and, more crucially, earnestness to Ésimésac. The real treats of the film however are Gildor Roy and little Sophie Nélisse. The latter bounces around with positivity, playing the titular character’s lovable yet never overly cute sister. When she falls ill in the latter half, sucking much of the buoyancy out of her, the viewer can genuinely feel the sadness of the event. As for Gildor Roy, he plays the ‘strongest man the village’ with aplomb and nuance. He is seemingly made out to be the villain of the piece in the early goings considering how large his shadow and thusly his ego are. His readiness to help out the train company and belittling of the town’s communal garden project are strong enough indications that he is a villain. However, as the plot progresses, there is clearly more than meets the eye to his originally simple motivations and Roy deserves a ton of credit for creating a satisfyingly multidimensional character.

Unfortunately, however many things the film gets right, it fails to earns top marks for nearly an equal amount of other ingredients. It would also appear that much of the missteps are of Pellerin’s own doing. Whether this is to be expected or not is another interesting matter altogether. After all, as previously explained, film screenwriting is not his forte. No one would claim he lacks creative flair or the capacity to weave a solid story, but what works in a collection of shorts might have difficulty translating well to the big screen given that expectations in both media differ. Sometimes, it has to do with decorative details, other times the deliberate decisions to drop story elements or mix them up purely for dramatic effect. The fact that Ésimésac is 25 years old physically and mentally yet has only been walking on this earth for two is not dealt with to its true potential. In fact, it is brought up so rarely that one wonders why that was part of the exposition at all. Then there is the matter of the communal garden and the need to bring water via a pumping system. The townsfolk go to Riopel, pleading him to build some instruments to assist them even though they have no money to pay the necessary fee. Ésimésac even goes so far as to claim that with his strength (he and Riopel are gifted with super strength), he can bring some water to the garden on his own. Strangely, this point is never touched on in any serious way again. Ésimésac just goes off to work with the train company afterwards, which inadvertently makes the townsfolk comes off as misguided as Riopel lambasted them for being when he predicted a garden was no guarantee for success. Stranger still is how Ésimésac’s relationships deteriorate the more time he spends with Riopel on the train tracks. The viewers can probably guess the corporation will not fulfill its promises, but that is neither Ésimésac nor Riopel’s fault. In fact, they earned some money to help their neighbours and families. There is even a scene in which the protagonist is shown to have a growing ego because he fires some friends for not working up to par. Guess what: they were also drinking on the job. Who wouldn’t fire them?

The film can be applauded for embracing a surprisingly moody finale. Whereas the first half is decidedly upbeat, the second delves further and further into some rather dark territory, all the way up until the final few frames. This being a family film first and foremost, it will not surprise anyone that Ésimésac ends on a positive note, yet even that is peppered with some solemnity. All in all, it is an intriguing experiment from Luc Picard and Fred Pellerin. The two have become to be loved so dearly by their fellow Quebeckers that the film will, in all likelihood, do well this holiday season, regardless of any faults that astute movie watchers will try to point out.

-Edgar Chaput