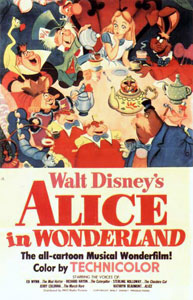

Directed by Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson, and Hamilton Luske

Written by Winston Hibler, Ted Sears, Bill Peet, Erdman Penner, Joe Rinaldi, Milt Banta, Bill Cottrell, Dick Kelsey, Joe Grant, Dick Huemer, Del Connell, Tom Oreb, and John Waltridge

Starring Kathryn Beaumont, Ed Wynn, Verna Felton

I should not pride myself in my ability to not be bored stiff by black-and-white movies, or by a supposedly stilted style of acting present in films from before the 1960s. There is a perception in the world, though, that audiences under the age of 30—I’m nearing the precipice of being on the opposite side of that line, but not yet—are, for the most part, unable to deal with older films or engage with them properly. On one hand, I bristle at the stereotype, not just because of my love for film of any age, but because I know from writing for this website, as well as from interacting with others online, that there are passionate cinephiles under 30. Of course, there are people around my age who couldn’t care less about silent films—see newly minted Oscar winner Jennifer Lawrence for proof—or the black-and-white era or subtitled films. But the same goes for people over 30, or people over 60.

There is, however, one aspect of old Hollywood that I find difficult to fully accept, and it’s specific to Walt Disney Feature Animation: sequential storytelling and filmmaking. It’s not rare for an animated film, even now, to have multiple directors; the difference between animated movies being made today versus those films Disney made in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s is that co-directors are no longer essentially working on one specific sequence of a movie, and nothing else. Of course, there’s precedent for Disney’s sequential style, as evidenced by the many package films they made in the 1940s, literally sandwiching shorts into a feature-length running time. More than most of the animated features produced while Walt Disney was still alive, Alice in Wonderland is exceptionally sequential, often to its detriment. There’s a bit of a paradox here: Lewis Carroll’s novels Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There are extremely episodic, thus a cinematic adaptation that’s equally episodic should be successful.

But something about the Disney version feels awfully flat. I wonder if the inherent issue is the source material, which seems patently unfilmable. Certainly, the issue isn’t an inability to create the strange world of Wonderland, either in animation or in live-action, as we’ll see next month with the execrable Tim Burton remake. The problem is that there’s no discernible story, at least none which seems readily transferable to the medium of film. What is the plot, or even the conflict, of Alice in Wonderland? Alice enters a dream world known as Wonderland, peopled with various strange people, animals, and inanimate objects, all of which speak to her. And then she wakes up at the very end. The end. I am, true, being reductive in describing what happens in the 1951 film, but I’m also not being inaccurate. What does impress me about the film, after revisiting it so many years since my childhood, is how instantly iconic so many of its elements are in spite of being barely present. Think, for example, of the Queen of Hearts. This red-faced harridan, whose “OFF WITH THEIR HEADS!” exhortation for her playing-card henchmen to eliminate any enemies, is immediately recognizable and realized through ink and paint. Verna Felton, whose voice we all know from movies like Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty even if we don’t know her face, is a perfect choice to bring to life this fearsome, dangerously unhinged villain. The Queen of Hearts is memorable. The Queen of Hearts is scary. The Queen of Hearts is in 15 minutes of Alice in Wonderland.

Here is a case of our memories playing tricks on us, because does it feel like she’s in so little of the film? I’d say not. Perhaps the Cheshire Cat—also in scant few minutes of the 75-minute movie—feels more like a supporting character, but if there is any truly opposing force in Alice in Wonderland, it’s the Queen of Hearts. A counterargument, I imagine, is that the antagonist throughout this story is either Alice herself, or all of the strange creatures she meets. She is, to be fair, always looking for a way home or demanding an explanation about what’s going on in this daffy universe. No one provides her with any answers, because there are no answers; Wonderland is chockablock with nonsense, the very opposite of rational thought or logic. So, sure, it stands to reason that Alice in Wonderland won’t have a typical conflict between a protagonist and antagonist. This, though, feels more like an excuse someone makes after the fact for a movie whose source material is equally alluring and foolhardy to adapt.

As Mike pointed out on our new podcast, for a book that I categorized as unfilmable, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has inspired countless retellings on TV and in film. But the language of cinema isn’t purely visual. If it was, no one would bat an eye at Alice in Wonderland, because the source material is mighty tempting to make real, to lift from the page into something tangible. Each place Alice stumbles into, from the mad tea party to Tulgey Wood to the Queen of Hearts’ palace, is crying out to be brought to life. Yet there is no connective thread between these settings aside from a vapid, vacuous, whiny lead character. (My memory of the 2010 live-action film from Walt Disney Pictures is that that film’s Alice, played by Mia Wasikowska, is less whiny, but no less empty a vessel.) Because there’s no story here, there’s really no movie here. This film is less a cohesive whole, more a scattered, impatient mess. It’s telling that Alice in Wonderland has 18 songs in its 75 minutes, with 12 more either on the cutting room floor or repurposed for other scenes or movies, such as a song that would eventually become “The Second Star to the Right.” Yes, many of these songs don’t last for more than 30 seconds, but why do they even exist? Whatever music you remember from Alice in Wonderland isn’t likely the “Caucus Song” or something so tossed-off. (Or, if you’re me, you’ll recognize the melody from its appearance in a rearrangement that can be heard in the Fantasyland section of the Disney theme parks.)

So much of Alice in Wonderland feels as if the animators behind the film were still living in the 1940s, an era mostly typified by the package film, such as Saludos Amigos or Fun and Fancy Free. These movies lived or died by the quality of each of their shorts—I might even say Fantasia deserves the same categorization—not by the expectations of a typical full-length feature. I have my issues with these package films, but story isn’t one of them. I could easily say that my expectations for this movie—one I’ve seen bits and pieces of over the years, but likely haven’t seen in full in 15 years or more—were incorrect, and that revisiting it on Blu-ray might make me warm to it more than I did this time. But I wonder if that’s just an excuse for bad filmmaking, much as people saying that some clearly offensive, bigoted thing they said is secretly satire. Are we just shielding a bad movie by looking at its flaws and seeing in them something charming?

I feel a little guilty calling this a bad movie, but by the basic standards of cinematic storytelling, it fails. There is no conflict in this film, simply a series of disconnected bits of weirdness. Famed Disney animator, and one of the Nine Old Men, Ward Kimball once said he thinks the film doesn’t hold up because each of the directors tried to top his fellow helmers in terms of memorable strangeness. Here’s the weird thing, to me: comparing this to Pinocchio or Dumbo or Fantasia, I’m not sure this feels nearly as loopy. Nothing here tops the Pink Elephant sequence in Dumbo, not by a long shot. Even if you take out the connection we have to that film’s lead character, the image of menacing magenta pachyderms is branded on the brains of anyone who watched it. Here, we have goofy playing cards, a pothead caterpillar—fine, fine, it’s hookah he’s smoking, but we all know it can signify something a bit more potent—and singing flowers. Something about this movie’s imagery feels less naturally psychedelic and more forced. Alice in Wonderland has moments of striking visuals, but is otherwise a forgettable piece of folly. That Disney has let it bloom into latent popularity decades after its release is a marketing success. Alice in Wonderland is many things, but it’s a mess more than anything else, and possibly the worst example of why sequential filmmaking can be so damn distracting.