Written by Arthur Alsberg and Don Nelson

Starring Dean Jones, Patricia Harty, Nicky Katt, Larry Linville, Claudia Wells

When people speak of the possibility of alternate dimensions, they leave out the one closest to us all. We like to imagine a universe so similar to our own, nearly identical to the world in which we live if not for one difference. Maybe in one dimension, Bill Clinton was ousted from office, not just thrown up for impeachment. Maybe in another dimension, HD-DVD won the high-definition home-media war instead of Blu-ray. Or maybe, in some beautiful reality, Scott Norwood didn’t miss that field goal in the Super Bowl against the New York Giants. The possibilities are tantalizing because they are literally endless. In all the wonder and curiosity, however, most of us fail to recognize that there already exists another universe snuggled up tightly to ours, if for one unique and sometimes hard-to-perceive shift: people in this other universe do not act like regular human beings.

These are creatures who stand erect, have opposable thumbs, and the power of speech. Oh, they say they’re humans, but you and I can see through the lie if we look hard enough. They dress like us, they live in homes like us, and they work like us in regular jobs, at places like the local bank, hospital, or school. But these are not human beings; they’re not even Stepfordized. No, they are clearly aliens of humanoid lineage. The most disturbing element of these false humans is that they only exist in the minds of our fellow, real citizens. You won’t find these folks actually working in your bank or school. Instead, they exist as a fantasy in the minds of screenwriters and directors in Hollywood. As these fakers grow in prevalence, though, more real people assume that these alien figures walk among them, that their actions are normal as opposed to mightily moronic. What possesses filmmakers to create worlds so like our own, but slightly skewed? Why do they feel the need to operate within an alternate dimension whose sole difference is that its inhabitants act like idiots?

And why are we so finicky in accepting this unique world, in which many ridiculous stories and characters dwell? Each romantic comedy, each slice-of-life dramedy, each genre that isn’t clearly untethered to reality may operate in its own bubble, but each bubble comprises a small part of this alternate dimension. Sometimes, we like the bubbles. Sometimes, we love them. And sometimes, we ignore them, allowing them to sputter out of existence. What makes one bubble of stupidity less palatable than others? What makes one implausible mini-universe unsuccessful where others soar? Can it be that one is less distractingly unreal than another? When has that stopped anyone from paying to see a treacly, misshapen husk of a romantic comedy, despite failing to be either romantic or funny? Do filmmakers or the people funding them simply miscalculate what people are responding to in the present as opposed to what they responded to in the past? Perhaps.

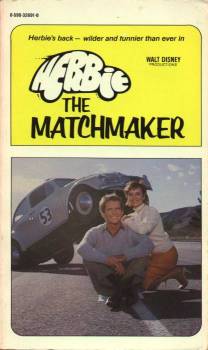

That is, I assume, the chief reason why Herbie, The Love Bug tanked as a television show. It should matter that the series, which lasted only five episodes as a midseason replacement for CBS in the spring of 1982, was concurrently boring and idiotic, a classic example, some might say, of why television cannot be better than film, why it cannot truly be art. And there is no question: Herbie, the Love Bug is, much like the films that inspired it, a bad example of its medium. You may find charm in the decidedly antiquated sensibility of the misadventures Herbie got into on the silver screen and on the boob tube, and seeing as the supposedly lovable VW Beetle inspired six movies, a TV-movie, and this TV series, he wasn’t lacking for familiarity, if not overall popularity. As bad as this show is, however, it proves only that the film and TV industry stays the same even as we perceive it to shift dramatically. The mediums of cinema and television have always been littered with trash; perhaps the ratio of quality to garbage was much more skewed in the latter direction back in the 1970s and 1980s, but to compare the two, now or then, is foolish.

Comparing the two in the case of Herbie, the Love Bug is especially foolish because the TV series, at least in four of the five episodes that aired, was clearly structured like an epic-length movie. (Because, as we all know, the next best thing to a new Herbie movie is one that’s over 3 hours long, stretched out like a miniseries.) Of course Disney re-edited the footage into a 2-hour TV movie, but they couldn’t have struggled too much about what chaff to cut from the meager wheat they had to work with. Herbie and the low-stakes adventures he got entangled in with one owner or another never felt particularly cinematic. That he and his owner should be relegated to the Siberian climes of quickly canceled television is perfectly appropriate. In the past, Mike and I have discussed these dregs of Disney cinema, dressed up as feel-good family pablum about a hapless human tied to this needy, obnoxious, nosey humanoid car. In some respects, Herbie, the Love Bug is an improvement on the loosey-goosey insanity of Herbie Goes Bananas, at least because the show doesn’t really go so far over the top that you can’t see how far it’s flown upwards. What it lacks in batshit craziness, sadly, it boasts in sheer, excessive monotony.

The high concept of the TV series is the same as that of the films: there is a car who’s nicknamed Herbie. Herbie is a Volkswagen Beetle, and has apparently been imbued with humanity. (The wisest thing the old films, this show, and the Lindsay Lohan reboot ever did was not explain how this is possible. Seriously.) The car is alive. And that’s it. This time, Herbie and his erstwhile owner, Jim Douglas (Dean Jones, who I’d dub the poor man’s Jimmy Stewart if it didn’t feel like an insult to Jimmy Stewart, poor men, and whoever a poor man would actually say is his version of Jimmy Stewart), begin to settle down in the Los Angeles area. Jim has an unsuccessful driving school—partly because the building he operates out of looks like the adobe shack where you stop to get food one day because it’s cheap, you’re hungry, and too lazy to drive to a name-brand fast-food chain or a respectable restaurant, thus ensuring that you can only blame yourself for the gastronomic aftermath; and partly because Jim is, as evidenced by how he happily encourages his students to assume they’ve pulled off amazing automotive tricks Herbie performed by not allowing them control of the vehicle, the worst driving instructor in history—and he’s got his old racing glory courtesy of his car. Then, he meets a divorced mother of three after foiling a robbery at the same bank where he hopes to receive a loan to keep the school solvent. He weasels his way into the family of this woman, Susan, even nudging out her prospective fiancé, a family-film version of a douchebag named Randy, who only leaves the scene after the fourth episode, when Jim and Susan get married. Before the wedding, the jilted ex managed to be the president of a bank who had time on his hands to concoct various schemes to take down his romantic rival, such as cross-dressing, stealing cars, and trying to slip roofies into a woman’s drink. Because this show is, to quote the man, y’know…for kids!

I’ve made things, perhaps, too convoluted when Herbie, the Love Bug doesn’t even deserve that treatment. Jim’s budding relationship with Susan doesn’t move as quickly as that of Dharma and Greg, but it’s awfully close. I binged on these episodes—well, relatively speaking; I wasn’t mainlining Arrested Development or House of Cards—but it’s safe to assume, because there are no clear markers of time, that only a few weeks have passed between the pilot and the fourth episode, let alone the final one. So Jim and Susan meet, fall in love, and get married within a month. Is this an impossibility in the real world? Of course not, and I’m sure you could find me some couple in history that not only followed this set of circumstances (OK, take out the part with the living car), but stayed together for more than a year as man and wife. Compared to this scenario, however, all those high-school sweethearts we’ve heard about stayed together until they passed away on the same deathbed, not just a handful. For Jim and Susan’s relationship, as well as the dichotomy within her family, to make a lick of sense, these two lovebirds need to have Cybill Shepherd-and-Bruce-Willis-in-Moonlighting-esque chemistry. Jones and Patricia Harty are normal enough people, mildly attractive, but they seem more bemused at each other’s presence, as if they’ve been put into separate rooms, handed the sides of their dialogue in a two-character scene, and told to act as if they’re attempting to placate a child who’s this close to having a violent, that-creepy-kid-from-Looper-level temper tantrum. These are not people with a sizzling sexual connection, nor do they have modestly pleasant banter to volley off against each other. Jones and Harty have about as much chemistry as the models in the section of the Lands’ End catalog showing off the clothing intelligent urban professionals of a certain age should snatch up so they’re not morbidly embarrassed at the next summer retreat in the Hamptons.

You may have noticed, by now, that something about the Herbiverse drives me up a wall; maybe it’s as simple as me not understanding what it is with people and cars, the strange bond that has become commonplace, almost as natural as breathing, in modern society. We detail our cars, we wax them, we name them, and we treat them like our desk at the office, decorating them with doodads that announce us as…why, as individuals! Yeah, so what if you drive a Prius? My Prius has a bumper sticker that encourages other drivers to coexist! Plus, it’s decked out with a vanity plate only I can understand, thus invalidating its very existence! And my Prius is named Tony. Yours is named Charlie? Well, your car has a stupid name. Mine is better because it is mine. The Love Bug, a film whose success in 1968 should not go unmentioned and is surprising if incredibly disturbing, was not likely what kickstarted this notion of personalizing our transportation—we do this to every inanimate object, because it’s the only way we can stay sane and relate to the those items that make up our lives. What is profoundly baffling about the way Jim Douglas interacts with Herbie, especially in the TV series, is twofold: first, no one is bothered by his relationship to the car, despite his clear inability to hide the fact that Herbie is alive even though he’s presumably had years of practice; second, Jim Douglas HAS A RELATIONSHIP WITH HIS CAR. Dean Jones has more chemistry with metal than with a flesh-and-blood woman.

And here’s the thing: Dean Jones has always had more chemistry with Herbie. The romantic relationships in the films were a secondary storyline, because the real, consensual love affair was between a man and his transport. Herbie was prone to threatening suicide when he thought he was not being valued appropriately by his human owner. Herbie, the iconic face of a Disney franchise, was essentially Cameron Diaz in Vanilla Sky. (You remember Vanilla Sky, right? The movie where Cameron Crowe traded in his winning, affable, singular auteurist streak for ambition, failed, and then backed away from any discernible personality in the future? Of course you do.) If you wanted to be an apologist for the Herbie film series—and I don’t believe that term applies to my co-host Mike, who genuinely loves these things—you could say that this is both an accurate reading and intentional. The filmmakers want the relationship to be between Jim and Herbie, or Herbie and whatever non-Jim person is saddled with him for 90 minutes. Accepting this—and I think that’s a poor excuse for the other plots, riddled with bad writing between two characters who can interact in English, not a honking horn, but whatever—does not eliminate the problem in the TV series, whose bare thread of a concept is predicated on a human/human romance. Here, unlike in the films, it’s Adam and Eve, not Adam and Herbie. What’s more, Herbie is all but pushing Jim into the marriage with his front bumper, but the dude might as well be marrying a block of wood. The relationship that needs to matter here is not the one Jim has with Herbie. That’s been built and cultivated over nearly 15 years’ worth of movies. Yet, it’s telling that the theme song tips us off to what really matters in this show to Jim: his car. The lyrics to the song—I’m linking to a full episode here, but do yourself a favor and stop watching after the opening credits—include lines like “He’s bright and he’s sassy,” and “Herbie’s my best friend,” the latter of which is caterwauled, shouted to the high heavens by Jones, whose choice to sing the theme song (or maybe he was forced, I don’t know) is the first sign of the cover-your-eyes-with-your-hands-so-you-don’t-have-to-watch embarrassment to come in the next 4 hours’ worth of show.

[vsw id=”KcbLWnNRuf0″ source=”youtube” width=”500″ height=”300″ autoplay=”no”]

Jim’s relationship with Herbie is disturbing, yes, but so is the reaction from the other “humans” on the show. (Again, they can try to fool us, but we’re too smart for you, Hollywood. We know they’re really aliens.) To my knowledge, the other characters are never let in on the idea that Herbie is a living thing, even Susan’s youngest son, Robbie. He sees Herbie during a hospital stay in the final episode, but that can be laughed off by the adults and older kids as just crazy little Robbie seeing things again! “Oh, Robbie, you little scamp, you’re always making things up!” “But Mom, this time, I’m telling the truth!” (Susan’s response, cut before the jump to the new scene, is something like, “Robbie, do you want to visit Dr. Melcher again, with those nice, upside-down electric headphones he likes to make you wear? Remember the arrangement?” Oh, what? You think I’m making that up? You think I’m letting my warped mind do the talking? PROVE ME WRONG, INTERNET.) Now, aside from the fact that it is an eternal drag for Jim to not be honest about Herbie, what’s most distracting is that no one bats an eyelash at how uniquely weird Herbie acts whether or not Jim is “driving” him.

If Jim said, “Oh, Herbie? He’s a real car. I don’t know how, I don’t know why, but he’s a living thing. He drives himself. He can communicate with me and with others, and retaliates by spitting oil at people’s ankles if he doesn’t like them. And he’s been known to try to kill himself just to make certain I know who’s the dominant one in our relationship,” people in real life would react by calling the police or doctors or simply hail down a passing mobile mental institution. But we know it’s true. Anyone watching Herbie, the Love Bug is likely familiar with the setup, probably because they’ve seen one or all of the movies in theaters. So which is more exciting: a world where all of the characters know (or learn within the first episode) that Herbie is alive, thus allowing them to join him on his exploits; or a world where only one man is aware of Herbie’s real existence, and is desperate to hide it from everyone around him because he fears…some backlash? (By the way, the reason why Jim hides Herbie’s true spiritual form from everyone else is beyond me. Hell, his mechanic friend—and boy, does Jim go through mechanic sidekicks as fast as he goes through his girlfriends, amirite, fellas—doesn’t seem to know Herbie’s actually alive based on some comments in a late episode.)

Jim’s actions further enforce that this entire show—or at least the arc spread throughout the first four episodes—is a big, honking Idiot Plot, as Roger Ebert would say. Everyone has to act like a moron because otherwise, the script fails. In the third episode, for example, Jim is caught in flagrante (or so Susan thinks) with another woman. The specificity of who the woman is—a fellow race car driver as well as the woman Jim hooked up with chastely in Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo—and why Jim appears to be kissing her on the couch of his new apartment—the woman’s drunk and Jim’s just trying to get her to rest off the booze, when Susan barges in, hoping to tour his new digs—are almost unimportant because they fly in the face of logic. Why, of course Jim will have a bachelor party at the same time that Susan is planning to visit Jim’s new apartment! And of course the party will be thrown in the middle of the afternoon, and consist of unfamiliar men, Susan’s jilted ex (who threw the party), Jim, and the female driver drinking whiskey, scotch, and other heavy liquor! What’s most frustrating is endemic in almost every modern romantic comedy: the lack of a simple, definite explanation where one exists and can be provided succinctly. Susan bursts in to see her prospective lover with some hussy, splutters in fury, and Jim can merely gasp out, “You don’t understand! I can explain! Insert rote, non-informative declarative statement here!” Why doesn’t Jim say, “I was helping my friend down to the couch because she’s very drunk and needs to rest. I did not and would never hook up with another woman. I’m in love with you, Susan, and that’s the end of it”? Aside from the last sentence sounding awfully suspicious, it’s because the screenwriters needed something to happen in this episode, desperately. So Jim just looks like a tongue-tied dolt because, y’know, conflict!

Herbie, the Love Bug is, as Mike said on the show, something of a progenitor to the TGIF lineup of the early 1990s, as well as the various shows the Disney Channel has made excessively popular over the past decade. I can acknowledge (as well as shudder over) the show’s influence, but that doesn’t mean it’s any damn good. We often, I fear, ascribe quality to something influential simply because what came afterward wouldn’t exist if not for that first thing, such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, a film that’s often deemed the best of animation because it was the first of animation. Now, you can lay down the tar, feathers, pitchforks, and torches: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is a solid film, each second better than all of this TV show combined. That said, I’ve never embraced it as much as others do, especially considering the jaw-dropping jump in quality from that to the next Disney animated feature, Pinocchio. I like Snow White. I adore Pinocchio. One started a genre; the other improved it. Starting something influential isn’t the same as expanding upon it, which is far more important.

So Herbie, the Love Bug may have inspired a whole generation of writers, even if it’s not nearly as well-known as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and for good reason. Thankfully, it’s more important to me because it represents a finish line, one I’ve been dreaming of for many weeks. Finally, I am finished with the Love Bug series. I can wash my hands of the whole business, no longer plagued with nightmares in which a mysterious white VW Beetle stalks me, forcing me to get in so I can truly understand and follow the Tao of Herbie. Herbie, the Love Bug is something in my rearview mirror, something I never have to watch again. There are films on our podcast calendar I dread watching; now, however, I can say that no such films feature Herbie. There will be other movies set in this universe of idiocy, other films populated with alien humanoids, but I will be then, as I am now, forever watchful. Hollywood can try and fool me with this fancy alternate dimension; by now, thank God, I know better.