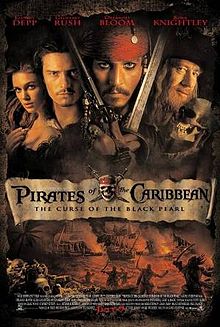

Directed by Gore Verbinski

Written by Ted Elliott, Terry Rossio, Stuart Beattie, and Jay Wolpert

Starring Johnny Depp, Orlando Bloom, Keira Knightley, Geoffrey Rush

Captain Jack Sparrow is the worst thing that ever happened to Johnny Depp’s career. The prevailing wisdom is that the constantly soused pirate is what vaulted Depp to superstardom, and though it’s accurate, I don’t think this financial leap represented a positive for his qualitative growth as an actor. Some people have found a balance between being legitimate actors and movie stars. George Clooney, Brad Pitt, and Matt Damon come to mind. (Sadly, not every one of the 21st-century Ocean’s Eleven qualify as stars. Sorry, Eddie Jemison.) This trio are easily among the most recognizable faces in film, this generation’s respective answers to Cary Grant, Robert Redford, and Henry Fonda. Their appearance in a movie doesn’t assure its financial success—honestly, Clooney’s continued stardom is almost entirely separate from the work he does. Each man, though, can turn on the charm when required. What they’ve learned, possibly from the director of the Ocean’s trilogy, Steven Soderbergh, is how to make a movie for themselves and then make a movie for the studios. For every Solaris, there’s a Michael Clayton. For every The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, there’s a The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, and so on.

Johnny Depp is a curious case, too, one whose career has exploded over the last 10 years, thanks in no small part to his work in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl. Depp was always present in modern cinema, having set innumerable hearts atwitter in 1990 as the title character of Edward Scissorhands, coupled with his work on 21 Jump Street. He’d established himself, by the early 2000s, as a quirky heartthrob, one who chose to rely more on idiosyncrasies than his natural good looks even when working with Tim Burton as the lead of Ed Wood and Sleepy Hollow. You get the sense from watching him in Chocolat that he’s uncomfortable just coasting on his appearance, that he needs something strange out of a role, something to latch onto that might make stock characters more palatable. (I remember, for example, that in the commentary for The Curse of the Black Pearl, one of the writers points out he was only willing to spout a crucial but exposition-heavy monologue if the word “miscreant” was employed.) However, his work with the Walt Disney Company, starting with Pirates and extending to one of the most unfortunate and unfathomable box-office successes in recent memory, Alice in Wonderland, has begun to smack of selling out.

Before I get too deep into this, let me state the obvious: Johnny Depp is wonderful in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl. His performance was rightly nominated for a slew of awards in 2003, including the Best Actor Oscar (an award he should’ve won over the actual winner, Sean Penn, as well as fellow nominees Bill Murray, Jude Law, and Ben Kingsley). As displayed in the original film, Captain Jack Sparrow is a wholly surprising and delightful creation, a shrewd amalgam of pop-culture figures as disparate as Keith Richards and Pepe Le Pew. Even after a decade, I still find myself laughing at Captain Jack’s antics and his entire being, a lively and playful commentary on the Hollywood vision of 17th-century pirates. Through the script and Depp’s work, Captain Jack manages to be self-aware, self-conscious, grandiose, and multidimensional…in the first movie. I feel the urge to add that qualifier—“in the first movie”—to most of what I write about this film. As enormously fun and entertaining as The Curse of the Black Pearl is, the three films that followed it from 2006 to 2011 are among the most messy, bloated sequels in Western cinema.

The lesson that Johnny Depp took from the clear and massive success of The Curse of the Black Pearl isn’t really the same one director Gore Verbinski, producer Jerry Bruckheimer, screenwriters Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, and Disney itself took. This, however, doesn’t mean that their takeaways weren’t equally detrimental. Depp decided people liked Captain Jack Sparrow so much that he might as well play a variation on the character in everything he did going forward—except in rare cases like The Rum Diary, where he assumed playing a younger Hunter S. Thompson type would work as well for the cult of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. What the filmmakers and Disney took from the first film’s success wasn’t just the obvious and correct assumption that audiences loved Captain Jack Sparrow and the world he inhabited so much that they’d be willing to see a follow-up or two. No, what they decided was to double down on mythology (here, I give a tip of the hat to previous guest/friend of the show Rowan Kaiser of The AV Club for pushing me to this point on Twitter), making it so the characters everyone embraced wholeheartedly were cogs in a vast, unending, confusing, yet mindless machine.

But before that, let’s look at Depp’s career trajectory, which has arced to a depressing high since his starmaking moment in 2003, so deflating merely because we may never be able to bring him back down to Earth. Back then, it was well documented that Disney executives like Michael Eisner thought Depp’s oddball cavorting would ruin one of their summer tentpoles. (It’s also well documented that Eisner thought Finding Nemo would be Pixar’s first relative failure, or at least financial and critical proof that they weren’t perfect. Say what you like about the legacy Eisner created and left behind, but in 2003, his predictive powers were on the fritz.) Who knows, then, why Captain Jack Sparrow feels so appropriate, so apt, as a character who’s instantly, immediately iconic, alongside Indiana Jones and James Bond as one of the great adventurers in cinema. The other characters in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl are, to varying degrees, bemused by Captain Jack’s antics, but straitlaced on the whole. (Proof that even the original film’s script was rewritten on set is visible in the funny scene where the one-dimensionally honest Will Turner hears about Captain Jack’s prior ordeals and, mimicking the louche libertine, asks aloud if that explains why he acts so strangely now.) Still, Captain Jack’s weirdness isn’t alienating here. Frankly, he’s analogous to the Genie in Aladdin: the proceedings are enlivened by their presence, and darkened by their absence, strongly emphasizing how much these movies rely on their MVPs.

And the script for The Curse of the Black Pearl—also credited to Stuart Beattie and Jay Wolpert, who worked on the film before Elliott and Rossio came onboard with Bruckheimer—provides Captain Jack enough humanity—his feverish obsession with the Pearl that sets him on a deathly rivalry with the mutineer Barbossa—so he never feels totally detached from the action. Captain Jack is this series’ Han Solo. As such, you can see why audiences flocked to him and wanted more from him. However, Depp mistook this as an invitation to play Captain Jack Sparrow again and again, with or without pirate makeup and costume. Depp’s continued collaboration with Burton plays a large part; they collaborated on three films prior to Pirates of the Caribbean, and five more over the last 7 years. What was so enjoyable about his quirk as Captain Jack Sparrow in 2003 has become rote now. We were blown away by his work in the first Pirates because we weren’t expecting it. Now, we expect his oddity, and Depp rarely delivers more than that; thus, his performances offer diminishing returns.

After the widespread success of The Curse of the Black Pearl, Depp could do whatever he wanted, or at least he had more leeway. As his stardom’s expanded, I think it’s safe to assume he’s punching whatever meal ticket he wants. Moreover, if we assume that his films afterwards are representative of personal choices against the backdrop of bigger budgets, then what Johnny Depp wanted was to make movies his kids could watch. Oh, sure, some of his films—Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, better than most people give it credit for, comes to mind—aren’t family-friendly. You could even make an argument that the Pirates franchise has such truly grim imagery that it’s both totally antithetical to what a “Disney movie” is and should’ve garnered the films harsher ratings than PG-13. But they are Disney movies, based on a theme-park attraction; they can only go so far. Movies like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Alice in Wonderland are different, sure, in that they aren’t the blandest possible family-film product. They, like the second and third Pirates films, are garish, trading familiarity for grotesquerie. Where Eddie Murphy turned away from his adult audience and trademark visceral, profane comedy, pandering to kids and churned out painfully namby-pamby pablum, Depp chose to tailor his off-kilter attitude for a wider, primarily younger audience. This benefits no one, except for the stars and those who help line their pockets with cash.

Captain Jack Sparrow, in the original film, is lightning in a bottle. I don’t blame Depp, Verbinski, Bruckheimer, and company for trying to recapture the perfect combination of humor and pathos represented by a pirate whose addled personality is his greatest asset, a fast operator who’s the smartest one in the room precisely because no one assumes he’s got any brains left after drinking so much damn rum. While these basic character traits are repeated in the sequels, the writers and Depp do so to a point where Captain Jack is essentially a superhero. (I don’t mind the cliffhanger-esque ending of the second film, despite the massive, almost laughable debt it owes to The Empire Strikes Back, but it does end with Captain Jack gleefully diving into a sea monster to his all-but-certain-but-of-course-not-he’s-the-hero death.) It’s the same thing that happened to Bruce Willis and John McClane throughout the Die Hard series: an everyman whose quick thinking and ability with a weapon is spun out into the baffling, unrealistic power to live through any and all attacks from even the worst possible evildoers. Depp, in particular, has been chasing this mix of script and character ever since, and can’t harness it by himself or with the help of others.

Turning Captain Jack Sparrow into a mythic figure, as opposed to a person who attempts to force others to buy into his self-created mythology, is the core of the problem plaguing the other Pirates movies. Yes, the plot of Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl is enormously convoluted, as it is with most modern action/adventure movies. What makes the film work so well after 10 years, even with the specter of the sequels looming over it, are the characters. These are, perhaps, not all uncommonly intelligent people—the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern-like pirates played by Lee Arenberg and Mackenzie Crook try to be menacing, but are merely delightful and daffy thanks to their constant yet never cartoonish ineptitude. But the decisions they make don’t often strain personal plausibility. As the series progresses, however, the decisions Jack and Will and Elizabeth and others make feel less like natural actions. The script requires them to maybe fall in love or get jealous or double- and triple-cross each other so the story can move forward. They act as they’re told, not as they choose. Any swashbuckling epic is, I admit, allowed to not be entirely grounded in realism, but even the best films of the genre aren’t overly fantastical in how characters act and react.

After the first film, what the filmmakers assumed everyone wanted was more. More of everything. (Precisely because the other sequels are disastrous, Gabe, Mike, and I spent as much time on the podcast qualifying our praise as I have here as we did on praising the first film. Mike, of course, says he may well think the third is the best in the series, to which I can only say…that’s Mike for you.) Everyone loved Captain Jack Sparrow, so let’s have more of him, and why not throw in some half-baked, unbelievable romantic subplot with Keira Knightley while we’re at it! Everyone loves action, so let’s have more sequences of explosions and gunfights and such! The swordfight between Will Turner and Jack in the first film is one of its highlights, so let’s top it! And so on.

Before I fault the series for its excesses, I should play devil’s advocate for a second and acknowledge that such is the operating theory in Hollywood for all sequels. Few continuations honor the previous film’s story and characters, and adequately expand the world of that story and the characters who populate it. Films like Toy Story 2 or The Empire Strikes Back are called out frequently and correctly as great examples, as are the latter two Batman films directed by Christopher Nolan. The reason why these stand out is because the people creating them were telling good stories, not just excuses to make a ton of money. (As ever, I point out that I am not so naïve to assume that financial elements don’t go into the thinking for almost every sequel, among them the films I name-checked. But these weren’t created solely for the money.) Also, with such sequels, it’s not a case of “Well, after the first film, there needed to be a follow-up.” The Toy Story franchise is comprised of three different films, none of which really required there be a new film afterwards. Nevertheless, each film is different, telling a unique story that adds more dimension to Woody, Buzz, and friends.

In the Pirates of the Caribbean series, on the other hand, the problem is that each film doesn’t tell a different story. We either get a sluggish reprise of what we’ve already seen, or, in the case of the second and third films, an unnecessarily sprawling would-be epic tome spread out over two films. We have, I hope, reached the tipping point of filmmakers deciding that the best way for them to make a trilogy is, instead of following the examples I cited, to tell one story over two movies. (Since movies like The Dark Knight and Toy Story 3 made a hell of a lot of money for their studios, you’d think more studio executives would fall in step behind Christopher Nolan and John Lasseter, not Verbinski and the Wachowskis.) What I find most perplexing about this mostly commercial but somewhat creative decision is that it has categorically failed in multiple franchises. Financially, you could look at Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest and point out that it was an enormously successful film, the highest-grossing film in the series, barely beating out On Stranger Tides thanks to a massive worldwide take. And The Matrix Reloaded, another famous second entry in a fake trilogy, is the highest-grossing film in that franchise. What about the third films, though?

Well, fun fact: they didn’t do so hot, relatively speaking. If you look at the numbers, you could easily say Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End did quite well, thank you very much. The first film grossed $305 million domestically and the third grossed $309 million. Close, but At World’s End wins, right? Until you notice that Dead Man’s Chest made $423 million. If we looked at the number of tickets sold—which, frankly, is how box office results should be tallied because that’s more quantifiable—we’d see that At World’s End sold 44 million tickets. Not too shabby, but disappointing next to the 50 million Curse of the Black Pearl sold and the 64 million Dead Man’s Chest sold. For the Matrix series, the statistics are similarly telling: 33 million for The Matrix, 46 million for Reloaded, and 23 million for Revolutions. Perhaps two examples do not a thesis make, but if we take these snapshots of cinema as legitimate evidence, it’s obvious that filming a second and third film back-to-back isn’t the wisest business decision. It doesn’t work.

Or, at least, it doesn’t work when you force people to make films that don’t have a good reason to exist. Not every sequel is bad. But those that are shot back-to-back typically are a step below the first film in the series; they occurred because someone at a studio felt the impatient urge to capitalize on the opportunity as fast as possible. The second films in the cited series did quite well, only because everyone loved the debut entries so much. Goodwill poured over into bigger numbers. Word of mouth did not. No matter how good The Curse of the Black Pearl is, there is a sequel-shaped cloud that hovers over the film. The filmmakers made every bad decision people behind a sequel to a beloved first film could make. Mythology is the opposite of what people wanted or demanded, but it’s what they got, coal in the summer-movie season stocking. There are, a fan of the follow-ups would say, enough hints to the mythology in the first film that are broadened throughout the series. Davy Jones’ locker is mentioned, and one of the running gags is all about parlay as written in the so-called Pirates’ Code. So where’s the harm in bringing those ideas to completion?

Chiefly, they aren’t ideas, and what Elliott, Rossio, and Verbinski do with these loose concepts is inflate them with so much hot air that they explode all over us poor, unsuspecting onlookers. I enjoyed the second Pirates, but not because I finally got to see what it’s like to be on Davy Jones’ crew of damned pirates. No, what I enjoyed (and we’ll see if I still do in a month) were the jaw-droppingly impressive effects and some of the derring-do, totally divorced from the overlong, top-heavy plot machinations. That swordfight Mike cited on the podcast, the one where Jack, Will, and others have a massive fencing match on a large spinning wheel, is emblematic of the film’s excess, but I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t fun. The wheel fight doesn’t top the battle Jack and Will have 30 minutes into The Curse of the Black Pearl, but the former is also not a pale shadow of the latter. The hard emphasis the writers and director place on the faux-angsty romance between Will and Elizabeth, though, and a tortured father-son relationship between Bootstrap Bill and Will, serves only to pad the running time and to bore the audience/appeal to young women. (This, in spite of the clear fact that Depp and Orlando Bloom, by their existence, appealed to large swaths of women.) During these scenes, I’m Milhouse on the school bus, whining and wailing, asking when we’ll get to the Johnny Depp-sized fireworks factory.

In effect, the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise slowly turned audience members into Milhouse. All we wanted was a return to form, a return to what made the first film work so well in the face of such impressive opposition. Captain Jack Sparrow is a force of nature in the second and third films, though the conclusion of Dead Man’s Chest takes the Han Solo comparison I mentioned too far. What people wanted from the sequels was something they could never get again: surprise. It’s a fool’s errand for the filmmakers to try and harness that charming and daring attitude once more, but because the money was dangling in front of them, they couldn’t resist. Let’s be honest: people (I include myself here) should’ve known a sequel wouldn’t offer the same freshness Captain Jack Sparrow represented. We knew what to expect, and we got that, not something new. The filmmakers and Johnny Depp, for a short time, found gold in the form of Captain Jack Sparrow and Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl, a gloriously fun, whip-smart, and thrilling adventure that capably stands next to other iconic summer blockbusters. They kept panning for treasure, and won’t stop until they find it again. I fear none of us will be able to convince them to stop trying. Considering how great this first film in the series is, it’s heartbreaking to see how Disney and Johnny Depp can’t let go of a dream that will never come true, thus ruining our memories of why we ever liked Captain Jack Sparrow or Depp in the first place.