Directed by Toshiaki Toyoda

Written by Toshiaki Toyoda

Japan, 2011

How often is it said that one person’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter? Maybe that is but a cliché which has emerged out of tired movie scripts. Be that as it may, most people in the world do claim entirely opinions on the nature of guerrilla fighters, their objectives and the strategies by which they go about achieving said objectives. It all depends on whose side the individual or group is fighting on that helps influence the nomenclature. What about someone who is literally fighting for themselves, who has no allies, no assistants, who operates as a recluse yet when he or she strikes, people pay attention? Monsters Club, from Japanese director Toshiaki Toyoda, takes a look at one such curious person, at what makes them tick and what might, just might, make them change their mind about their current lot?

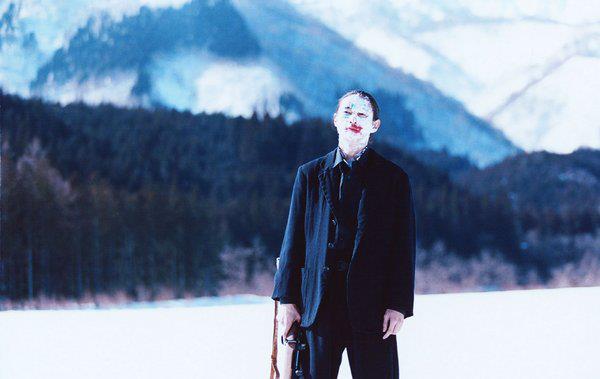

Ryoichi (Eita) is a one man bomb squad. He lives as a hermit in the snow covered Japanese countryside, as far away from civilization as he can afford. The cabin he dwells in, old, creaky, belongs to the family, of which precious few members are left following a series of unfortunate accidents and the one tragic suicide by his older brother. He cooks his own food, listens to music and, when the time and target is right, prepares bombs that are subsequently sent back into the cities at the addresses of CEOs and various other people of important stature. In one of the film’s few long, detailed inner monologues, Ryoichi reveals to the audience his fury towards modern society. As such, he has chosen to fight back at the establishment via his bombs and calling card, ‘Monster Club.’ It is unclear whether he is slowly going insane after such elongated time in the wilderness or if otherworldly beings are actually soliciting him, but at one point odd looking fellows sneak into the cabin to meet him, one is covered in white with bright red lips and the other resembles a human with its skin peeled off. Following some discomforting, silent encounters with them, they are eventually revealed to be his two deceased brothers who have come to ask him some life altering questions.

It does not take much time to understand that Monsters Club is one of those films that will either leave audiences wanting more character study, lingering shots of the Japanese country winter wonderland and provocative dialogue exchanges, or dumbfounded and annoyed at how excruciatingly slow it is, maybe even pointless. The latter group will have understandable qualms. After all, Toshiaki Toyoda’s pacing is deliberate to the point where even at a scant 75 minutes or so, the movie might actually appear long during some stretches. Pack your patience with you when seeing this movie, make no mistake about it. Yet, even though such complaints are acceptable, the fact of the matter is that the carefule pace allows for an excellently woven study of one delusional man’s mind. Not delusional in the sense that he has completely lost his marbles (the appearance of two ghosts might contradict that statement, however). Delusional in the sense that the protagonist, by operating much more as an antagonist really, has lost his way with delusions of fighting a just cause via what he accepts as just means.

The character of Ryoichi is angry, although at first it appears he is solely angry at the world for how it does not fit what he deems to be the correct and proper way to embrace individuality. The institutions, political establishments, laws and 21st century consumerist culture, instead of allowing for full freedom, have all trampled on it instead. The people and advertisements will make society believe it is benefiting from freedom whereas in reality everyone is but conforming to standards dictated by a select few. These words have been heard before, in print, online and on newscasts and documentaries and at this stage enough is enough. Ryoichi is determined to combat the ‘system’ and in the process earn his freedom.

That, however, is the surface level material the film deals with. Once his brothers return from their graves to pay him a couple of visits, things take an altogether different turn. Suddenly, they are at the same time scolding him for not going through with the ultimate statement against the system, that being suicide, and compelling him to join the members of his immediate family, most of which have already entered the after-life (save one sister who makes two brief appearances). Ryoichi reminisces about a scene at a picnic table on a beautiful day with his family, and how comforting that day felt, how everything fell right into place. Now, the theme of the picture has been slily turned on its head. If Ryoichi is really that disgusted with the world and misses his family that dearly, why not end it all right there and then?

What follows will be up to the viewers to discover. The conclusion to Monsters Club is just as satisfying as it is enigmatic. It falls in line with a lot of how the events, characters and ideas of the story are presented. Director Toyoda brings a touch of elegance, of grace to the proceedings, contradicting the nature of everything that is happening on screen yet far be it from this movie reviewer to explain how none of it works. It does work, and brilliantly at that. The camera frame is carefully manipulated throughout the entire film, with slow panning shots, judiciously chosen cuts and tone-perfect lighting. Monsters Club is infused with poetry, violent poetry perhaps, but poetry all the same. While the first half is concerned with the character’s anger, the second coolly shifts ideas, ultimately lending the story with a far more emotional impact than could have been predicted by anyone at the start.

The movie reinforces the common that no one really makes films like the Japanese. Is it because their cultural inclinations have them refuse to make films like the rest of the world or results in them simply being unable to? The answer is unimportant in the grander scheme of things. What matters most is that the Japanese speak with a completely different cinematic language, and Toshiaki Toyoda, who also wrote the script, can be included among the artists who push the boundaries. Their horrors films feel different, their action movies feels different, and who else with come up with a premise like the one that drives Monsters Club? Actually, a fair number of people could come up with it, but probably no one else would play with it as is the case here. Movies like Toyoda’s makes being a fan of international cinema incredibly rewarding.

Juggling ghost story, society commentary an family drama, the film offers plenty of food for thought all the while giving said food emotional weight. It looks fabulous, sounds fabulous, is funny, is scary (viscerally and intellectually), yet somehow all of this stems from a weird little movie. Your cordially invited to join the Monsters Club. Just mind the bombs and the flesh eating ghosts.

-Edgar Chaput