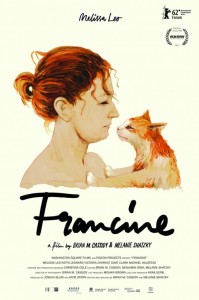

Directed by Brian M. Cassidy and Melanie Shatzky

Written by Melanie Shatzky and Brian M. Cassidy

U.S.A./Canada, 2012

Everybody is wired a little bit differently, which is what makes each person a fully fledged individual. Of course, such idiosyncrasies do not always result in the most respectable or even relatable humans beings. While individuality is a wonderful product of the human experience, there are plenty of examples which clearly demonstrate that whatever aforementioned wiring is not helping someone integrate smoothly into society. Such people might be mentally unstable, perhaps criminals or they simply not have the capacity (nor the will) to associate with others. Two young filmmakers, Brian M. Cassidy and Melanie Shatzky have collaborated on a new project along with one of independent film’s most recognizable names, Melissa Leo, on one peculiar project that observes the behaviour of one such unorthodox person.

Melissa Leo stars as the titular Francine, who, at the start of the picture, is being released from prison. The reason for her incarceration is never revealed to the audience, nor does that element of information appear to be very important for the time being. The fact of that matter is that she is a social outcast of sorts, considering that she was required to pay for some sort of sin with time in prison. However, her demeanour in the minutes, hours and days that follow indicate that something else is at play. She is particularly quiet around other people, preferring not to speak to them at all whenever possible. She lands a job as a clerk at a pet store, although her social ineptitude translates poorly to customer service, hence she is fired shortly thereafter. Her subsequent jobs are all related in some ways to animals, with each successive segment making it abundantly clear that Francine is frighteningly uncomfortable around her own kind, yet feels at ease with dogs, cats, mice, horses, etc. However, her devotion to animals changes nothing about the fact that her social awkwardness may lead her into trouble again in the future.

Watching Francine, it seems interesting to note that it is the product of a directing duo. The reason is simple: the Brian Cassidy’s and Melanie Shatzky’s film is a terrifically meandering piece of cinema. There is a thread which carries the movie from the first minute to the last, even though it is only really detectable in the final few frame when the protagonist begins to behave in ways that help inform the audience why she was in prison at the start, but for the most part the movie has an extremely loose feel to it. The narrative is as free-flowing as can be, as the directors promote the exploration of Francine as an individual with her own set of very noticeable quirks via an episodic experience. Each segment helps give dimension to Francine, although anybody who does not award the film their full attention will certainly be left wondering about halfway through why exactly the film is supposed to be about given that is nearly feels as if nothing of significance is happening. That is partially true in that nothing of note is occurring in the traditional movie sense where big events are written in scripts to shape the story and propel it forward. Events do occur in Francine, although they are small, intimate and solidify the movie’s status as a character study in the purest sense, only short of being a documentary if only because it stars Melissa Leo, who as far as we know is not an ex-con nor does she eat dog food (although…).

How does this relate to the point of interest that the movie was directed by two people instead of the more traditional one? It is an idea that struck this reviewer’s mind when coming to terms with the fact Francine’s strategy in developing its central figure in any dramatically satisfying way was to have the faux-documentary camera follow Francine around with such little intrusion as possible that there are moments when a viewer could be forgiven for understanding that what Francine is doing at her job, or what she is paying attention to is more important than the character herself or anything resembling a plot. Her second job takes her to a stable, where she feeds, washes and brushes brilliant stallions, and while this portion of the film continues to cement Francine as a social pariah madly in love with beasts, there are times when the specific character study takes a rest and the directors choose to focus on the brushing of a horse. Another moment occurs when Francine, after having walked through a furniture story, discovers a small death-metal concert happening just a short walking distance away. Francine’s adventure suddenly halts for a few minutes as Cassidy and Shatzky prefer to hold the camera on the band, Francine and the precious few other audience members, some of who are almost a little too pumped up by the music. It seems like the sort of film that would best suite a single director’s vision considering how loosely structured it is. One wonders how the decision making process evolved and how the duo went about capturing Francine simply living her life.

The most impressive result of the incredibly loose narrative is that not only does the viewer get to learn about Francine, but also some interesting bits of information on animal treatments, especially later in the film when the character works at a veterinary. Francine practically pulls off double duty as a piece of fiction and a documentary, something not a whole lot of films can claim to be. It seems doubtful anybody walking into this movie would anticipate learning how to perform euthanasia on a sick dog…and see it happen.

Melissa Leo herself is quite strong in the lead role. She also has to be, if for no other reason than the fact that she is literally in every scene of the movie. Leo has proven many times in the past to be a ferocious talent, capable of creating multilayered characters with rich performances. Her work in Francine is extremely quiet and might represent some of her most subdued material yet. By playing someone who dislikes talking to people, it is not as though she gets to say very much. The devil, as they say, is in the details, and Leo’s appreciation for detail shines through, as her many subtle mannerisms go a long way in creating this sad, pitiful character whose heart is mostly likely in the right place although cannot seem to break through the figurative cocoon she shields herself with from other people.

Francine is a small, small picture, yet one with a distinct vision for which two confident filmmakers came together to bring this little project to life. It is a film filled with small moments, a film which depends on the small moments even in order to resonate as much as it does.

-Edgar Chaput