Directed by Andrew Stanton

Co-directed by Lee Unkrich

Written by Andrew Stanton, Bob Peterson, and David Reynolds

USA, 2003 and 2012

Pixar is in the middle of its growing pains as a studio. The public still loves them, but a good chunk of the media wants them to return to their glory days; any deviation from perfection makes us, apparently, more suspicious of the studio’s imperviousness. Though their last two new releases, Cars 2 and Brave, made an impressive amount of money at the box office, neither was as critically beloved as the four films preceding them—Ratatouille, WALL-E, Up, and Toy Story 3. There’s no question it was a letdown to most audiences and critics that their latest films weren’t as moving or thrilling as others, but is it really fair to blame Pixar? Is it fitting to attack a studio for not being flawless every time they take a swing? No, the fault, as the writer once said, is not in our stars, but in ourselves. Qualitatively, we were spoiled by the Emeryville, California-based animation company. It’s not wrong of us to be disappointed when an actor, director, or studio doesn’t manage to equal genius each time they release a project. But it’s perhaps not rational of us to lash out when Pixar takes chances that don’t always work as well as we’d like them to. (Yes, even Cars 2 represented taking a chance.)

2012, especially, has been rough for Pixar. Brave was a consistently entertaining tale of a mother and daughter who have to mend their relationship quickly or lose it forever. But it didn’t pack the same potent punch as the studio’s best; for some, Brave being good simply wasn’t enough. Coupled with news of continuing franchises—such as next year’s Monsters, Inc. prequel—and 3D conversions to earlier films—Monsters, Inc. itself will get one this December—Pixar’s felt less like a creative explosion of talent lately and more like a company driven solely by the almighty dollar.

Regarding the 3D upconversions, no more have been announced past Monsters, Inc.; still, it wouldn’t be surprising to see Pixar announce an upconversion for The Incredibles to coincide with its 10th anniversary in 2014. (Pro tip, Disney: convert it to IMAX, not 3D. You’re welcome.) People have short memories, of course. We like to assume whatever outrage we may feel about pop culture is not only appropriate, but also timely. And yet people have forgotten that the first two Toy Story films got a 3D upconversion back in the fall of 2010. This week, however, Pixar’s gone to the upconversion well with the 2003 hit Finding Nemo.

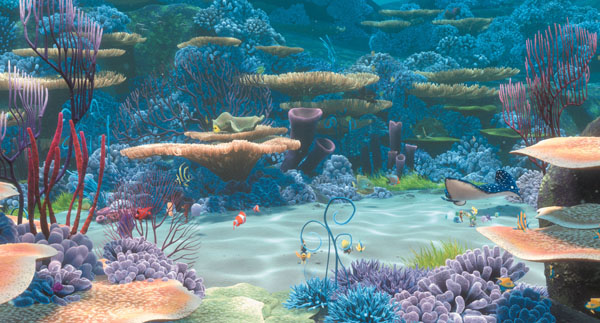

If nothing else, Finding Nemo 3D serves as a welcome reminder of why we think so highly of Pixar Animation Studios and the people who work there, why we get so possessive and frustrated when Pixar doesn’t achieve brilliance all the time. Pixar deserves credit for not being like other studios, doing a sloppy, rushed job on converting this quest story (or their other films) into 3D. They went back to the footage and re-rendered it entirely; certainly, Disney is capitalizing on the still-ongoing 3D craze. They’re just doing so in a more decent fashion. The 3D, as such, is OK, but can’t hide the fact that Finding Nemo is a perfectly constructed story, boasting an extremely sharp, entertaining script and talented voice cast.

Finding Nemo 3D brings with it some baggage, though none that directly affects the film. This adventure, about a clownfish (Albert Brooks) on a journey to save his missing son with the aid of a forgetful blue Regal tang (Ellen DeGeneres), is still as exhilarating, fun, and poignant as it was when it was originally released 9 years ago. But within the last few months, rumors of a sequel bubbled up (and have since been confirmed by Andrew Stanton, who co-wrote and directed this film and would helm the second, currently slated to open in 2016). And then there’s this upconversion. Pixar’s efforts to avoid making a cut-rate upconversion should be applauded, even though the new format doesn’t offer many striking changes in the overall presentation. Hollywood has done far worse with 3D upconversions; that may be a backhanded compliment, but when it comes to 3D presentations, any compliment is welcome.

Because the animators at Pixar are so talented, the film looks no more or less exquisite now than it did in 2003. (There is one shot, lasting maybe three seconds, with some strangely choppy movement. It’s worthy of mention here only because the rest of the film is so filled with fluid, natural motion that it stuck out like a sore thumb.) Perhaps most distressing is that this film’s 3D upconversion not looking terrible is, honestly, a point of pride. Unlike almost every other 2D film presented in 3D, Finding Nemo looks fine in this format, just not essential. And that’s because no amount of technical attempts at immersion are even required to make this film succeed.

Written by Stanton, Bob Peterson, and David Reynolds, Finding Nemo is a shining exemplar of Pixar’s best work. The clever, winking humor that was a hallmark of their earlier films—fish crossing the “street” in the local reef’s neighborhood or a twist on the common saying “piece of cake”—is present but not overwhelming. There’s an impressive level of complexity to Marlin, Dory, as well as Nemo, and the supporting cast is both vast and well-tended to. Nemo, who goes missing when a diver/dentist catches him near a reef’s drop-off as a present for his niece, has an entirely separate story for the majority of the film, interacting with a group of aquarium fish who are uniquely attuned to the ins and outs of dentistry. Though they’re essentially the subplot, everyone, from a blowfish (Brad Garrett) to a starfish (Alison Janney) to the grizzled old veteran (Willem Dafoe, whose darkly masculine voice fits well for a character who masks a throbbing, innate pain), gets something to do. The script treats each character as having had a life before, during, and after the film.

It’s not just the characters and the film that have a beginning, middle, and end, it’s every tightly focused scene. The writers lay enough groundwork early on for so many payoffs, from what Marlin will learn during his trek through the ocean to how Nemo will grow and mature as a fish. This is all foreshadowing, but it never feels thuddingly obvious. We may imagine that Marlin will learn more about his fellow denizens of the ocean, but the script is intelligent enough to keep us guessing as to how. It shouldn’t be so hard for a family film to be both exciting and intelligent, not condescending to the younger members of the audience, but Finding Nemo stands out as a welcome exception, from the very first scene.

The opening sequence, in fact, serves as a microcosmic example of why Finding Nemo works so well, and how it could’ve failed otherwise. One boon of behind-the-scenes coverage is following the long road a film takes from pre-production to the final release. Knowing, for example, that Finding Nemo’s first 5 minutes—where we see how Marlin loses his wife, Coral, and all but one of their baby clownfish—was initially going to be split into multiple shorter bits that would be doled out throughout the present-day story is illuminating. First, it serves as an example that the industry as a whole hasn’t yet taken this lesson to heart: reshooting or reframing stories shouldn’t be seen as inherently negative. In animation, it happens often, and Pixar films are no exception. Most of the time, it’s proof that the filmmakers are willing to exercise any option for maximal quality.

More to the point, this detail puts the opening scene, as it stands, in greater context. Stanton chose to utilize a more fractured backstory in his live-action debut earlier this year, John Carter, giving us flashes of the lead character’s tortured history until a climactic fight scene where we’re given enough information to realize exactly what he’s been through before his trip to the Red Planet. (One hopes that John Carter, which flopped at the box office, will get a second chance soon. It’s imperfect, but big-hearted and fun.) In Finding Nemo, the longer it takes us to figure out why Marlin is so uptight and single-minded to the point of aggressive selfishness, the longer it takes us to sympathize with him as a character, outside of his plight. Opening with the scene emphasizes that Marlin will change, and how he’ll change. That Stanton was willing to fix this scene proves the power of being open-minded.

Thomas Newman’s score that’s an appropriate contrast between hope and concern, the confident helming from Stanton and co-director Lee Unkrich, the witty and lively script, and the vocal performances—with Dafoe and Geoffrey Rush as a helpful pelican among the supporting standouts—are as fresh now as they were nearly a decade ago. Finding Nemo may be best appreciated by people who have kids, if only because they’ll relate most closely to Marlin’s overprotective nature. But make no mistake: this film is extremely potent and easily stands next to Pixar’s other masterworks. Frankly, its script could take a spot next to Toy Story, for being swift, effective, and emotional without any dead weight. And regarding the 3D conversion that’s inspired this re-release, you could do worse. Or you could just see it in 2D, as it was meant to be.

Note. Though Finding Nemo 3D is mostly the same, there’s a new Toy Story Toon attached called Partysaurus Rex, where the lovable if neurotic green dinosaur (Wallace Shawn) meets a whole new world of toys that Bonnie (the toys’ new owner, in case you forgot) has in her bathtub. This colorful new short is perhaps the best of the Toy Story Toons, with extremely zippy pacing, a rave-like atmosphere, and scads of wit. There’s a moment here that may qualify as a “cheap 3D trick,” to put it in the words of Kermit the Frog, but it’s also arguably the only moment in the short or the film that follows it where the 3D feels necessary.

— Josh Spiegel