Many unsuspecting cinema-goers who clearly hadn’t read the reviews got quite a shock when they went into Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan expecting a nice movie about ballet. Black Swan is a fully-fledged (pun intended) horror movie full of fantastical elements – or is it? Horror it certainly is – fantasy, it may not be, as it is entirely possible that every uncanny event in the film exists only in the protagonist’s disturbed mind. Black Swan is far from the first film to play with the line between fantasy and reality, and it won’t be the last. What follows is a subjective list of some of my favourite reality-bending fantastical films.*

A Matter of Life and Death (dir. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1946, known as Stairway to Heaven in the US)

Unusually, A Matter of Life and Death tells the audience, before the film has even begun, that all the fantastical things they are about to see may exist only in the traumatized mind of Peter Carter. Peter has suffered a head injury in his fall which has caused a series of hallucinations. The Heaven he imagines is black and white, while Earth is filmed in glorious Technicolor. As his trial takes place in Heaven, Peter is undergoing an operation down on Earth on which his life depends, and the surgeon is played by the same actor as the heavenly judge (Abraham Sofaer). Until the last few scenes of the film, the only people with whom Peter interacts during his hallucinatory episodes are dead, i.e. figments of his imagination. In the last few scenes, his girlfriend June is subpoenaed as a witness, but the film ends before we  can find out whether she has any memory of this event. Conductor 71 borrows a book from Peter, but throws it back into his jacket pocket at the end, where it could have been all the time. The words at the beginning of the film and June’s conviction that Peter is suffering from hallucinations seem to suggest that the film should be read as the highly organized fantasy of an injured mind. However, it is equally possible to read all the events of the film as real, especially given the early scenes featuring Peter’s dead radio operator Bob (Robert Coote) and an angel (Katheleen Byron) which Peter is not witness to. Viewing all the Heaven-set scenes as real also embellishes the happy ending by establishing that both Peter and June will live until they reach grand old age.

can find out whether she has any memory of this event. Conductor 71 borrows a book from Peter, but throws it back into his jacket pocket at the end, where it could have been all the time. The words at the beginning of the film and June’s conviction that Peter is suffering from hallucinations seem to suggest that the film should be read as the highly organized fantasy of an injured mind. However, it is equally possible to read all the events of the film as real, especially given the early scenes featuring Peter’s dead radio operator Bob (Robert Coote) and an angel (Katheleen Byron) which Peter is not witness to. Viewing all the Heaven-set scenes as real also embellishes the happy ending by establishing that both Peter and June will live until they reach grand old age.

Where Black Swan bends reality in order to create a sense of horror and foreboding and its protagonist’s hallucinations eventually destroy her, A Matter of Life and Death allows it’s protagonist’s delusions to save him. Without a successful outcome in his heavenly trial, Peter will not survive his operation. Although Conductor 71 occasionally appears in a mildly sinister fashion, he is largely a comic character and his appearances are played for laughs. The death of Peter’s doctor (Roger Livesey) while looking for the ambulance to take him to the hospital is indirectly caused by Peter’s condition, but much more immediately and directly caused by Dr Reeves’ reckless driving, established earlier in the film. The fantasy in this film is overwhelmingly positive, offering hope that there may be life after death, the opportunity to meet with old friends (namely Peter’s late radio operator, Bob) and a demonstration of the overwhelming power of love in the universe.

Labyrinth (dir. Jim Henson, 1986)

Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland is the quintessential dream story. Everything that happens in the story is a dream, and definitely not reality. Jim Henson’s Labyrinth, written by Terry Jones, looks like it could be this sort of story. Sure, we don’t see Sarah (Jennifer Connelly) lie down a go to sleep, but we do see her fling herself onto her bed in a rage, and we imagine that she might have fallen asleep. She then enters a bizarre, magical world where nothing seems to make sense and she can’t take anything for granted, a world surely reminiscent of Wonderland, and the audience are all prepared to expect a dream story.

Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland is the quintessential dream story. Everything that happens in the story is a dream, and definitely not reality. Jim Henson’s Labyrinth, written by Terry Jones, looks like it could be this sort of story. Sure, we don’t see Sarah (Jennifer Connelly) lie down a go to sleep, but we do see her fling herself onto her bed in a rage, and we imagine that she might have fallen asleep. She then enters a bizarre, magical world where nothing seems to make sense and she can’t take anything for granted, a world surely reminiscent of Wonderland, and the audience are all prepared to expect a dream story.

Jones knows this, and so he sets his audience up to think that maybe they were right. Immediately following a sequence that actually is a dream sequence – a masked ball which Sarah hallucinates while under the influence of a decidedly dubious peach – he takes Sarah back to her bedroom and she lies down on her bed. A-ha! thinks Sarah, sitting up again – it was all just a dream. Thank goodness. And she gets up and goes to her bedroom door.

When she opens the door, she finds a particularly unpleasant area of the Labyrinth on the other side, and a troll-like creature shuffles into her room and starts symbolically piling stuff all over her until Sarah finally remembers that she has to save her brother.

The audience is still prepared, however, for this to be part of the larger dream. The story has been set up to suggest that all of this comes from Sarah’s mind – she reads the story of Jareth the Goblin

Alice in Wonderland (dir. Tim Burton, 2010)

In the years since the success of the Lord of the Rings films, it has not been especially fashionable to blur the line between fantasy and reality in high fantasy films that rely on creating secondary worlds. The success of The Lord of the Rings depends on believing in the secondary world absolutely and accepting it as reality, and so other films have followed suit.

In the years since the success of the Lord of the Rings films, it has not been especially fashionable to blur the line between fantasy and reality in high fantasy films that rely on creating secondary worlds. The success of The Lord of the Rings depends on believing in the secondary world absolutely and accepting it as reality, and so other films have followed suit.

Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland is a particularly interesting case, since it is based on a book that places its secondary world firmly in the realm of the unreal. The story is a sequel of sorts to both Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass and what Alice Found There. The film begins by apparently going along with the usual dream scenario and playing up to the expectations of an audience, who are assumed to know the story from the two novels already. So, Alice (Mia Wasikowska) talks with twin girls who are reminiscent of Tweedledum and Tweedledee, is proposed to by a man with similarly striking hair as the Mad Hatter (Johnny Depp) and observes a conflict over the colour of roses.

However, Burton turns all this on its head by insisting that his Wonderland, or ‘Underland’, is real. Alice is hurt when attacked by the  Bandersnatch and the plot rests on her eventual realization that Underland is not only real, but really in need of saving. When she eventually returns to our world, she sees Absalom, the caterpillar, in the form of a blue butterfly, offering a metaphor for her growing up, but also literally present as a butterfly. This film rests on removing any blurring of the edges of reality.

Bandersnatch and the plot rests on her eventual realization that Underland is not only real, but really in need of saving. When she eventually returns to our world, she sees Absalom, the caterpillar, in the form of a blue butterfly, offering a metaphor for her growing up, but also literally present as a butterfly. This film rests on removing any blurring of the edges of reality.

And yet, there remain the twins at the party, and the distinct visual similarity between Alice’s beau and the Mad Hatter. These seem to be there simply to play with the audience’s expectations, but it cannot be denied that they do leave a lingering sense of doubt as to exactly what is real and what is not that prevents the film from becoming entirely removed from its original source.

The X-Files: I Want to Believe (dir. Chris Carter, 2008)

Not a terribly well-received picture, the biggest complaint against this film is that it is no more than an extended episode of The X-Files. This is entirely true – the whole thing is just a long monster of the week story – I happen rather to like The X-Files’ monster of the week stories, so I’m quite fond of it. What’s interesting about it is, like several of the best episodes of The X-Files, it blurs the line between paranormal activity and self-delusion.

Not a terribly well-received picture, the biggest complaint against this film is that it is no more than an extended episode of The X-Files. This is entirely true – the whole thing is just a long monster of the week story – I happen rather to like The X-Files’ monster of the week stories, so I’m quite fond of it. What’s interesting about it is, like several of the best episodes of The X-Files, it blurs the line between paranormal activity and self-delusion.

The general tendency in The X-Files is to lean towards Mulder’s (David Duchovny) interpretation of strange events – the paranormal interpretation – because otherwise the show would be just another police procedural. However, there were several occasions, usually religious stories, when Mulder refused to believe there was any paranormal activity involved and Scully (Gillian Anderson) became the believer, because she is a practicing Catholic and Mulder is an atheist. These were the stories that blurred the line between what might really be paranormal and more mundane explanations. Rather than focusing on something that none of the audience were really likely to believe in, and therefore presenting it as real in a straightforward fantasy, these stories dealt with things half their audience might believe in and the other half might find ridiculous, so they left the question of what was real and what was not more open.

In the film’s case, our heroes have especially good reason to distrust the Catholic priest who is their apparently paranormal source, as he is a convicted pedophile. The film implies that there is some genuine paranormal connection between Fr. Joe (Billy Connolly) and the villain, Tomczeszyn (Fagin Woodcock), by having them die at the same time and not really providing a satisfactory alternative explanation for Fr Joe’s accurate visions. However, Fr. Joe is also shown to be completely wrong in at least one instance and his connection with the villain may be nothing more than a lingering antagonism relating to his own criminal past.

genuine paranormal connection between Fr. Joe (Billy Connolly) and the villain, Tomczeszyn (Fagin Woodcock), by having them die at the same time and not really providing a satisfactory alternative explanation for Fr Joe’s accurate visions. However, Fr. Joe is also shown to be completely wrong in at least one instance and his connection with the villain may be nothing more than a lingering antagonism relating to his own criminal past.

The first X-Files film, Fight the Future, focused on the ongoing alien invasion story that drove much of the TV series and, as such, was all-out, unequivocal science fiction complete with alien spaceship. General viewers, unfamiliar with the show, did not take so well to this, and this is why, in the second film, Carter is so keen to blur the line between fantasy and reality. He takes his film out of the realm of science fiction and into that of the crime thriller, giving it a supernatural edge and horror-like climax, but ultimately keeping the story fairly mundane and almost entirely plausible, the only fantastical elements coming from spiritually-based ideas that some of the audience may not consider to be ‘fantasy’ at all.

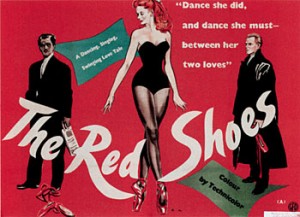

The Red Shoes (dir. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, 1948)

The Red Shoes is the third of Powell and Pressburger’s trilogy of Technicolor masterpieces, following A Matter of Life and Death and Black Narcissus (1947), a story of nuns in the Himalayas filled with tension and foreboding. The Red Shoes is the story of a prima ballerina, Vicky (Moira Shearer), who is forced to choose between her love for the composer, Julian (Marius Goring) and her love of dance, propelled by her obsessive director, Lermontov (Anton Walbrook).

The Red Shoes is the third of Powell and Pressburger’s trilogy of Technicolor masterpieces, following A Matter of Life and Death and Black Narcissus (1947), a story of nuns in the Himalayas filled with tension and foreboding. The Red Shoes is the story of a prima ballerina, Vicky (Moira Shearer), who is forced to choose between her love for the composer, Julian (Marius Goring) and her love of dance, propelled by her obsessive director, Lermontov (Anton Walbrook).

Almost all of the film is played as a straightforward drama, with the only fantasy taking place within the ballet written for Vicky, based on Hans Christian Anderson’s dark fairy tale, ‘The Red Shoes.’ During the ballet sequence, the film slides into the surreal, entering a fantasy-like state; but, at the end of the ballet, it returns to reality. However, right at the very end and at the climactic moment, the film slides into fantasy for just a moment or two.

Lermontov has forced Vicky to choose between her relationship with Julian and dancing, and she has chosen dancing. As Julian walks away to the train station below, Vicky is led towards the stage by an older woman. Suddenly, Vicky pulls away and starts to walk backwards. We see her feet, in the bright red shoes she wears for the ballet, looking almost as if something is pulling her backwards. Shearer moves her feet slowly and as if under pressure, as if something is forcing her to walk. Suddenly, Vicky perks up with a rapt expression on her face. She turns around and runs out of the building, down the steps – and right off a high balcony onto the train tracks below. As she lies dying (somewhat improbably, still largely in one piece) she asks Julian to take off the red shoes.

What makes Vicky turn around and run to her death? Has she decided that she loves Julian more than dancing after all and forgotten about the balcony? Has she decided to kill herself because she

It is not necessary to view the ending of The Red Shoes as fantasy – there are plenty of possible psychological reasons for Vicky’s actions and her odd movements may simply be the result of her confused state. But the way that final scene is filmed, along with Vicky’s final request that the shoes be removed, implies that just maybe, there is something even more sinister going on than a young woman’s obsession.

And with that we are, of course, back to where we started, for The Red Shoes is without a doubt one of the biggest influences on Black Swan. Aronofsky’s film is somewhat less subtle in its use of fantasy, but it blurs the line between fantasy and reality to the same effect. By presenting events that may or may not be the product of a damaged imagination, both films create a sense of deep unease and increasing horror that can only end in tragedy.

*I have excluded the equally excellent selection of reality-bending science fiction films that question the nature of reality, like The Matrix or Inception – that’s another article for another day.

Juliette Harrisson