For Norman McLaren form is everything. That makes sense given the medium he chose to express his art. Short films are, perhaps more than any other expression of film, succinct and to the point. The story is in the form, the vision is in the form, the art is in the form. To that end many directors have spent many years trying their best to manipulate the form. Film is malleable after all, that is the most breathtaking aspect of the medium. To see something so straightforward taken and twisted until it meets the vision of the artist is akin to the definition of art.

That is where Norman McLaren enters the picture. He was a master at taking the form of the short film and twisting and turning it until it fit his vision of art. Take a film like Dots for instance. A simple red animated landscape is the canvas upon which McLaren has decided to manipulate the form of art. The viewer sees the image on the screen changing and morphing. Grayish dots begin to appear within the middle of the bright red screen. Then those dots disappear, only to be replaced by more dots, and eventually by slashes, lines, and blocs of all sorts. Where are the dots coming from? Why is the image changing? What does the image change say about the artist, his art, the medium, and the viewer?

Those questions and many more are posed by McLaren in his short films. He was not content with providing the viewer with a standard artistic experience. He ripped and clawed at the senses of the viewer. He begged them to question what they saw in his films and then to take their questioning out into the real world. In Norman McLaren’s world the form was the window to the world. Through his art we can see a man who was afraid of the homogenization of society. He wanted us to be the dots breaking free of the red canvas, but all too often we remained the red canvas.

It’s at least a little ironic that some of McLaren’s most famous works, Begone Dull Care, Neighbours, and Pas de deux would come from the seemingly quaint land of Canada. Admittedly this image of Canada is one that has been carefully crafted by media and good intentions throughout the years. These media efforts have led to people identifying Canada and Canadians as wholesome, hard-working, quiet, and not likely to stir the pot. McLaren’s films gnawed away at these ideas. Begone Dull Care with its rhythmic jazz scratching allowed the world to see that Canada was more than hockey and quaint people.

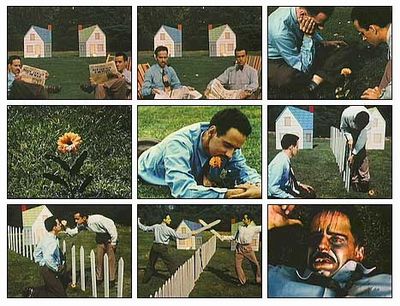

Later in his career the concerns McLaren had over homogenization took on new heights in such films as Neighbours. This, possibly McLaren’s most critically acclaimed short, attacked the very idea of homogenization. Society needs to be different, if it isn’t then it is doomed to eat itself and leave nothing of value behind. Neighbours presented a seemingly charming vision of suburban life, a vision that is quickly destroyed in a way that is fitting with people clamoring for the same possessions. Normalcy breeds contempt, and it is yet again Norman McLaren who uses the short film medium to show people the dangers of not stepping outside the box.

When all is said done Norman McLaren should be a household name. His innovations did as much for film as the works of Alfred Hitchcock, Jacques Tati, or Claire Denis. Yet McLaren will most likely never be spoken of in the same breath as those filmmakers. That is because McLaren chose to ply his trade and deliver his art in a style that even the most ardent of movie buffs don’t always make time for. Trust me when I tell you that Norman McLaren is one filmmaker you want to make time for; your film brain will thank me later.

Bill Thompson