Unsung Gems is a look back and reflection on great motion pictures that often slip under the radar of public consciousness , whether as ignored relics of a previous era, standout efforts overshadowed by competition or circumstance, or simply unseen classics damned by a lack of time in the spotlight.

Directed by John Mackenzie

Screenplay by Barrie Keeffe

UK, 1980

The urge to remain topical while discussing the past can quite easily be met when it comes to film, such is the sliding wall of time, faces and names that retains connection. But sometimes such links aren’t of the happy variety, such as the case here. Bob Hoskins, renowned actor of burly, diminutive disposition and with occasionally overlooked raw talent and expressive style as a thespian, last month retired from the acting business after it emerged he is suffering from Parkinson’s disease, a degenerative disorder made famous by Michael J Fox’s diagnosis in the 1990’s.

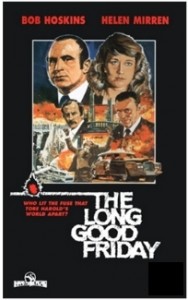

It puts a premature end to a glorious, critically acclaimed career which kept him in the hearts and minds of movie goers on both sides of the Atlantic and beyond, and even though we no longer shall be seeing him on the big or even small screen, he will retain his status as one of Britain’s finest acting exports. While he became world famous following Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and bagged an Oscar nomination for 1985’s Mona Lisa, the breakout role which put him firmly on the radar, and still proves to be his finest performance, is the 1980 masterpiece The Long Good Friday.

A sweeping and grandiose gangster film from a cinematic school which simply doesn’t make such films, Friday proves to be a gripping epitaph to the British retro stock of 70’s crime thrillers, pulling down the curtain on the anti-hero driven larks and hard amoral fiction of Get Carter and Villain, depicting a new era of uncertainty and changing horizons, a concentrated brave new world. In this time, old school geezers and hard cases no longer cut it, easily outflanked by smarter, stealthier and ultimately more dangerous foes of a polar opposite stock, both in business and in the dirty stuff.

Hoskins is Harold Shand, undisputed gangland champion of London, a cantankerous and heavy handed mobster with pretensions as an entrepreneur and delusions of grandeur to boot. He sees the dawn of the new decade as the opportunity to expand his empire into legitimate circles, taking on the ideal of ambition and bold brass in Thatcher’s Britain to build a fortune spawning development on the banks of the river Thames.

But his best laid plans, taking in paid off politicians and council representatives and corrupt police detectives, are slowly sabotaged and dismantled by a mystery enemy, a faceless foe picking off various members of his enterprise and whittling down his once unlimited resources, threatening to destroy his dealings with American investors who are quite clearly Mafia by trade. Don’t expect wiseguys to be behind the chaos, however, these are far more composed individuals, and the true threat is much more hardcore.

For someone who has been at the top for perhaps too long, Harold is understandably, and fatally, slow to react, faced by a conflict he doesn’t understand, has never experienced, and is completely unable to fight. Shaking down his own gang and roughing up street contacts are insufficient responses, indicative of an incapable defensive strategy. His growing incomprehensible rage tears away the thin demure of working class done good, revealing his primitive ways and blindsided attitude towards his work. His mantra, it seems, is “nobody f**ks with me”, and this unchallenged dismissive arrogance proves to be his downfall as his efforts to root out the cancer, and to hide the quickly escalating situation from his prospective business partners, become embarrassingly futile and deluded. While we see Harold’s empire crumble, we also see him go the same way. The brave new world doesn’t take too kindly to old hat.

The revelation that all of this, the destruction of everything Harold has sweat blood to create, was caused by the very same hubris and reckless disregard that his unchallenged decadence has imbued within his business, is the final damning indictment. Sitting at the top and continuing to look up has seen him go soft, seen him become careless, and has brought about the end. Even then, Harold’s response is violent and misdirected. Squeezed to the point of breaking, he lashes out, unable to think. His ultimate fate, a single shot scene of sensational prowess and simplistic artistic genius, sees the message finally sink in for our villainous protagonist. It’s not an easy home truth to swallow.

A brilliant and fitting climax, and one made unforgettable by Hoskins, who’s blistering and bitterly honest character study ascends The Long Good Friday from intelligent and bold crime epic into absolute classic. His Harold Shand is a blustering and haughty individual, baleful and dangerous as a wild animal, but also in small shades deeply vulnerable and knowingly flawed. This depth usually becomes apparent during scenes with Helen Mirren’s unconventional moll Victoria, as aristocratic as he is cockney, but fully devoted and loyal to a man only she sees a human side to. While Harold has his pride and ego wounded by the insidious attack on his business, he is genuinely hurt in the heart by the loss of an old friend, and by the betrayal which inevitably is discovered. Wounded, he turns to the facet that got him where he is; pure aggression and cynical violence, and finds it isn’t enough. As character studies go, it’s one of the very best.

Although Hoskins dominates proceedings, the work of director John Mackenzie is exemplary, mounting an incredible story of noir shades by Barrie Keeffe and showing a keen visual eye and great instinct for tension, shock and mood swings. Francis Monkman’s iconic, blaring score eschews on the memory and serves not only as a grand backing track to the action, but also as an unshakeable auditory motif, a keen representation of the great things brought down to earth, danger and peril mixed with upstanding scale. There’s also sterling work from the cast, particularly Mirren, as well as character actors Dave King, Paul Freeman (pre-Indiana Jones), Derek Thompson and highly recognizable faces in genre specialists P.H. Moriarty and Alan Ford. Also keep an eye out for Pierce Brosnan’s screen debut.

Incredibly, The Long Good Friday came close to never seeing the light of day, filmed in 1979 but not reaching cinemas until three years later, and very nearly being relegated to a heavily edited TV special. Only the intervention of George Harrison’s championing company Handmade Films, the same paladins who helped rescue Monty Python’s Life of Brian, prevented execrable compromises and gave the film a framing, and place, that it truly merited.

Such is luck. Had the TV deal gone ahead, an American release would have seen Hoskins’ thick London accent dubbed over. Instead, it reached the big screen with great fanfare, and Hoskins became a unique star as a result. A little over thirty years later, the great career may be over, but the legacy will remain, sparked, birthed and ultimately defined by what is potentially, nay probably, the greatest crime thriller the British film industry has ever produced. Haughty praise indeed, but fully merited on the strengths of not only a technical and creative display of excellence framing a brilliant plot, but also an acting tour de force from its breakout lead.

Bob Hoskins, we salute you.

Scott Patterson