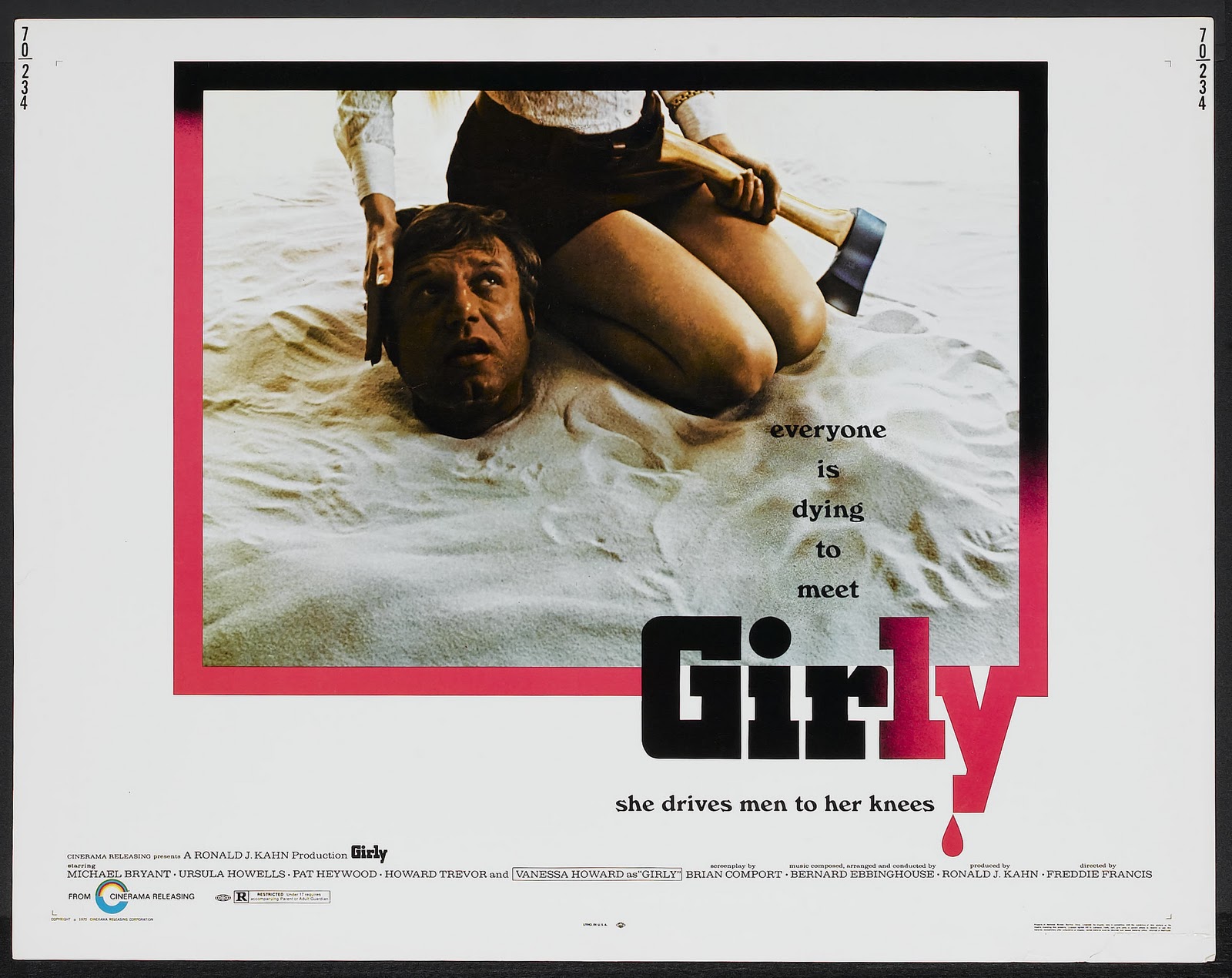

Girly

Directed by Freddie Francis

Girly is not the nightmarish blur of sex, color, and violence one would expect judging by the poster. Instead, it is a slow, psychological meditation, a playful look into the disturbing details of suppressed sexuality, morbid isolation, and the notion of insanity by proxy. We are led into a world fully contained within a decaying mansion, but we aren’t met with a parade of bloody horrors and gleefully violent imagery; instead, we are witness to a coy, clever game of cat and mouse, where no action or emotion is ever true. Comically depraved actions and lustful yearnings hidden behind a strange veil of morality are commonplace.

The male protagonist, or ‘new friend, played by Michael Bryant is the captive held by the psychotic family of Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny, and Girly. He is treated with care, and despite his initial fits of rejection, he learns quickly what other ‘friends’ could not; play the game and live, and so begins the slow and playful descent through thick clouds of sexual intrigue, jealousy, temptation, and murder. The new friend slowly twists himself into their lives through his own deviations from humanity. One by one, he gets the three females to relent their masks for him, toying with their lust and jealousy. One suspects Mumsy joyously tiptoes through this game new friend is playing, finding the wonderful irony of it. Nanny, however, is inexperienced with men, having always lived in Mumsy’s shadow, and Girly is impulsive, with unpredictable desires. It is Sonny who watches it all unfold before his male pubescent eyes.

The film is like a pieced-together car wreck; instead of seeing the violence of the crumbling metal and glass upon its impact, it feels more like the damage was done to each part of the car elsewhere, before being brought to the site. The scars and wreckage of the past lay waste in the mansion, and it is the character of Girly, played by Vanessa Howard, that holds it all together. With her ability to flip a switch and go from wide-eyed and innocent teen girl to a sinister woman, with carnal cravings and a taste for blood, she merrily prances through every moment of the film dangling every character from her finger. One almost roots for Girly and her wildly twisted ideas of love and friendship, which aren’t far from the desperate infatuations of most teenagers. Watching her playful routine, coupled with her desperate reactions to foreign emotions shapes an iconic image of femininity under the absurdist microscope.

James Merolla