With Girl Power in Gaming, we’re exploring the role of females in our favorite hobby for the month of September. The series will attempt to explore gender dynamics, pre-assigned roles and both positive and negative examples of female characterization in the digital world.

Just about a year since the beginning of the Gamergate “controversy,” conditions for women in gaming are, in many ways, as bleak as ever. I use the quotation marks to denote the absurdity of the situation, as whatever legitimate issues may have once lay at its heart were quickly subsumed by bigots seeking an opportunity to spread hate speech. To this day, insightful and outspoken women such as Anita Sarkeesian and Zoê Quinn continue to be bombarded with violent and misogynistic remarks on Twitter and elsewhere on a regular basis.

And within the games themselves, one could certainly make the case that the situation for women is improving, while still being bogged down by many of the same tropes and clichés. That being said, rather than attempt an overarching analysis of sexism in gaming, I’ll use my limited space here to concentrate on a game which has made admirable efforts (and, in many ways, succeeded, but more on that in a bit) towards telling the stories of women in interactive media: Gone Home.

The first-person point-and-click game places you in the shoes of college-age Kaitlin Greenbriar as she comes to the titular mansion after traveling in Europe for a year. Although the house belongs to her family, she finds it abandoned, and the game’s narrative tension lies in discovering where exactly everyone has gone.

It sounds like the set-up for a ghost story, but Gone Home uses it to tell a beautiful, realist tale of a family being torn apart. Central to the game’s narrative is Kaitlin’s sister, Samantha, who’s ran away with her girlfriend, Lonnie, so that she can escape the army and the two can be together. Somewhat more peripheral, but no less moving, is the story of Kaitlin’s parents, who leave the mansion to attempt to save their marriage at a counseling retreat.

The stories being told here are certainly part of what make the game feel as groundbreaking as it does. In a hyper-masculinized gaming landscape so often concerned with little more than boys and their toys, centering a story around two young women in love and suffering the pangs of adolescence makes for a radical move. Ditto for the failing relationship between Kaitlin’s parents, which implicates both her mother and father by hinting towards her infidelity and his addictions to alcohol and pornography.

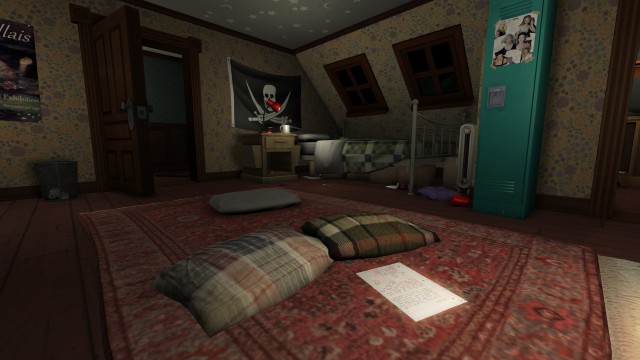

But beyond the content of what few story beats there are in Gone Home, what really makes the game stand out is the way they’re delivered. It makes clever use of its mid-nineties setting to feature artifacts which wouldn’t exist in the present day, and it’s through these artifacts that the story is told. Over the course of a series of diary entries, cassette tapes, letters, and other personal items, the case of the missing Greenbriars pieces itself together, revealing why Kaitlin finds herself alone in the mansion.

On top of being inextricably linked to an interactive form, the artifacts also serve to give the women of Gone Home voices, which gives their stories value beyond the mere virtue of their existence. It’s one thing to simply be experiencing a story about a young lesbian, but it’s something else altogether to hear and see it entirely from her point of view. It helps that Gone Home is brilliantly written and acted, and the naturalistic dialogue contributes greatly to the empathy the game engenders for Samantha. Above all else, she’s growing up, and Gone Home goes out of its way (but not obtrusively so) to show that she’s just another adolescent discovering Pulp Fiction and riot grrrl.

And in telling the story of Kaitlin and Samantha’s mother, Gone Home also moves beyond simply telling a female coming-of-age story and towards a narrative for women of all ages. We don’t get as much of the mother’s story as we do of Samantha’s, but we know enough to imagine that she feels trapped by her husband’s insistence on pursuing his literary failures. In revealing his pornographic magazine (another nineties artifact), Gone Home suggests his increasing lack of desire for her and the rejection she must feel. The game doesn’t exactly justify her infidelity, but it shows her as being victimized by a patriarchal relationship to the point where she has little other possible recourse.

Although Kaitlin functions as little more than our lens into this universe, the act of making her female, particularly within the context of the male-dominated gaming world, serves as the perfect finishing touch. We’re left to our own devices to imagine what she puts up with from men, but Gone Home positions her as a female ally for Samantha and her mother as they face their trials. Gone Home is unmistakably a story about women, and telling it through a female narrator hammers this point home.

We could use more stories like this, in gaming and otherwise. The statistic from E3 2015 showing that half of the games showcased let gamers play as female characters is encouraging, but lots of work still can be done in that direction. The more that work takes the shape of titles as great as Gone Home, the better for our culture as a whole.