A couple of weeks ago, Deadpool broke the box office. There’s never been a better opening weekend for an R-rated movie—of any kind. Deadpool is now Fox Studios’ most successful superhero film ever, it was well-received by fans and critics, and it also had a better debut weekend than Iron Man 2, Man of Steel, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, or Guardians of the Galaxy. (Whoa.)

To put this in very technical economic terms, Deadpool just made a crap-ton of money, and you can bet your last chimichanga that there are creative teams at at least three major studios trying to figure out how to reproduce that success, clone that mutant moneyhorse, and beat it into billion-dollar oblivion.

Hollywood will absolutely learn the wrong lesson from Deadpool. Haven't you ever noticed that they literally always learn the wrong lesson?

— Elle Collins (@AnotherElle) February 14, 2016

I wonder: Deadpool has always been the outsider's superhero comic/comics' outsider superhero. Will huge mainstream success alter that?

— Gail Simone (@GailSimone) February 14, 2016

Eternal optimist that I am, I think there’s a chance that Fox and their frenemies at Marvel Studios learn some actual valuable* lessons from the blockbuster they spent a decade being too cowardly and shortsighted to make until some brave, pure-hearted soul decided to leak some test footage less remarkable for its quality than its super-frickin’-obvious mass-market appeal.

* Please note that I use the world “valuable” not in the sense of “practical economic value,” but as in “Good Superhero Movie-making Value,” or as in, “Shut up, Moll, no one cares what you think.”

Anyhoo. In the best of all possible future timelines, here’s a list of lessons that Hollywood–and specifically Fox Studios–will learn from Deadpool.

1. Queer Heroes Can Headline Big-Budget Blockbusters

Wade Wilson is canonically pansexual, and not just in the comics. Tim Miller says so. Ryan Reynolds is joking (?) that Wade should have a boyfriend in the sequel. He’s the very first LGBTQ superhero to headline his own film.

This is definitely a watershed moment for bi/pan representation… but that’s not to say that it’s entirely a good thing. Cinematic Deadpool being canonically queer isn’t really something I’d call “good” or “bad” anymore than I’d call the character “good” or “bad”. Back before the movie was released, I spent thousands of words agonizing over the fact that Deadpool’s sexuality was probably going to be played for an edgy joke… if it appeared in the movie at all:

… Even among fans and creators who acknowledge or embrace Deadpool’s canonical pansexuality, there tend to be some pretty gross assumptions and stereotypes that go along with that. There are people who conflate Wade’s sexuality with his mental and physical illnesses, as Fabian Nicieza infamously did a few months ago. Deadpool doesn’t know who he is, so therefore he doesn’t know who he likes!

Or, there’s the implication that Deadpool is pansexual because he’s hypersexual. He’s a horny guy, so he’ll sleep with anyone and everyone. It’s kind of an easy shorthand for “edgy.” Sex with unicorns! Sex with men! Completely insane!

Basically, Miller and Reynolds want to be cool and funny and shocking, the same way that an old lady cursing is shocking, or four guys getting headshot by the same bullet is shocking. I just hope that they’re not using Deadpool’s “pansexuality” as a shield for making homophobic jokes with impunity. A Deadpool movie should be totally crude and offensive, but it should also be actually funny, and “LOL GAY” is not a punchline—it’s punching down.

After actually seeing the movie, I think I was basically right. Aside from some very mild homoerotic subtext, the movie hardly hints at Wade’s pansexuality. (Even claiming that there are “hints” is being very generous. Why should there be anything subtle about a Deadpool movie?) But there were plenty of jokes about gay c***sucking and girls with dicks, so our big watershed moment comes wrapped in some homophobic fratboy humor. Yay?

While I applaud Miller and Reynold’s willingness to remind the press that Wade isn’t straight, I still kinda get the impression that they’re playing that fact for an outrageous joke as opposed to a good-faith reminder about queer representation. (Is anyone involved with the production of this film or this character actually bi or pan? That would be cool, but I’m not counting on it.)

So, I remain pretty ambivalent about the fact that Wade Wilson, of all people, is our First Queer Cinematic Superhero, our highest-profile problematic fave. It’s not really Deadpool I have a problem with. I love Deadpool. This is more a problem with LGBTQ representation in general, and bi/pan representation in particular. We have so few bi/pan characters–and pretty much zero bi/pan male characters. Now we finally have this landmark “representational” character, but he happens to be hypersexual and crazy and offensive and all kinds of effed up. I’ll stand up for any character’s right to be crazy and oversexed and offensive—especially this particular character—but this is the problem with tokenism in general. When there’s only one of you onscreen, you can’t win—you’re either a toothless stereotype or an amoral mercenary who reeeally wants to screw Bea Arthur.

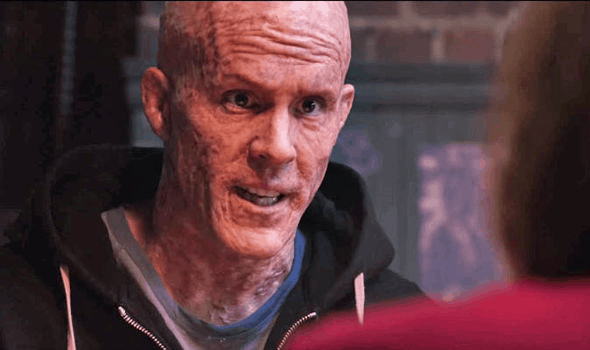

However, if Deadpool is going to be the template for a whole slew of R-rated, ultra-violent, sexed-up action-comedies, I’m actually really happy that its protagonist happens to be a queer, mentally-ill guy with an ugly face. When you think about it, Deadpool’s tone and genre aren’t actually that unique–the manic, cartoony superviolence and genre-skewering comedy aren’t anything that movies like Shoot ‘Em Up, Crank, Wanted, or Kingsman: The Secret Service didn’t do first. (Except that Deadpool was technically in development 10 years ago, so maybe it did do it first. Who knows? These timelines are hard to keep up with!) But unlike these other movies, which (despite their specific charms) invariably star white, handsome, straight antiheroes blessed with miraculous powers they don’t particularly deserve, Deadpool is inherently not about your typical, Gary Stu, self-insert everyman. Legions of seasoned readers and new fans can certainly identify with Deadpool, but they’ll be identifying with a canonically queer hero with chronic illness–while Deadpool isn’t always the “subversive” character he really should be, there’s something undeniably, awesomely subversive about that. And ideally, Deadpool will help major studios realize that LGBTQ characters can be big moneymakers, and there’ll eventually be more where he came from.

2. We can stave off the inevitable anti-superhero backlash by making better, more diverse, and more self-aware superhero films

Deadpool pulled off a pretty neat trick by pleasing both OG comic-book fans and general audiences. Read through a selection of the movie’s positive reviews, and you’ll see it being praised for “staying true to the comics” (by people who generally like superhero movies) and for “critiquing” superhero movies (by people who are generally ambivalent or negative about superhero movies). What the heck is going on here?

The answer, of course, is that you actually can do both those things at once, and good Deadpool stories frequently walk the uncanny line between homage, parody, critique, and nerdgasm. (It’s not everyone’s cup of tea, but that’s what the character is designed to do.) As nerd culture goes entirely mainstream, it’s not surprising that there’s a demand for movies that critique, parody, and transgress superhero tropes as well as endlessly reproducing them. If toxic comic-book fans and snooty newspaper movie critics have something in common, it’s their sad misconception that you can’t love something and make fun of its foibles at the same time.

Now, I’m not saying that Deadpool, the actual movie, did this particularly meaningfully or well. Cutesy Hugh Jackman jokes aside, I wonder if future Deadpool movies might manage to actually be the biting, satirical voice that this increasingly bloated genre so desperately needs.

3. There’s a market for smaller, narrower, and deeper superhero stories

Deadpool’s relatively tiny budget was the best thing that could’ve happened to it. By necessity, the movie had to focus on a relatively small-scale, low-stakes personal conflict. Wade’s out for revenge against specific people for personal reasons. There’s a pretty brilliant gag where he keeps forgetting his bullets and/or guns, keeping the action grounded and scaled-down. The film’s final action sequence literally takes place against an ironic big-budget Marvel backdrop. The punchline is that the spectacle is relatively small and unspectacular; the lesson is that action isn’t necessarily less entertaining or compelling because it’s smaller.

Not every superhero movie has to happen on an apocalyptic scale. (I’m not particularly optimistic that Fox is about to take this lesson to heart, given that their next big movie literally has the word “Apocalypse” in the title, but oh well.) But I think we should make the case for leaving the proverbial big bag of guns in the proverbial car more often. Fox is blessed with the legal rights to literally dozens of X-Men with compelling individual backstories and interpersonal conflicts, but they keep stuffing them into ensemble movies where The Fate of the World TM is always, forever, mind-numbingly at stake.

How do you top saving the world? You can’t! So why not go smaller? (Edgar Wright appears to have attempted this approach–literally and figuratively–with Ant-Man… Marvel Studios’ preferences for bland mediocrity over stylistic idiosyncrasy notwithstanding.) What about small-scale origin stories for fan favorites like Storm or Quicksilver or Beast? If Deadpool worked as a generic revenge flick, what about an X-Men buddy comedy or love story or heist movie? It’s 2016, and I’m losing patience with big studios who think that “superhero” is an interesting genre. Let’s get a little smarter. Stop giving us boilerplate superhero movies, and start giving us interesting, diverse movies with superheroes in them.

4. The X-Men are not the Avengers, and that’s part of what makes them awesome

In the Avengers franchise, Marvel Studios is riding a billion-dollar media juggernaut. Throw Spider-Man into the mix, crowd every available hero into the upcoming Captain America movie, and send it all hurtling towards a universe-shaking confrontation with Thanos… Basically, it’s unlikely that the studio’s basic formula is going to change anytime soon. As recent, more mediocre adventures like Thor 2 and Avengers: Age of Ultron prove, these movies don’t have to be particularly good to be mind-blowingly profitable. As long as the brand remains reasonably, blandly consistent and occasionally awesome, it’s probably here to stay.

With that said, I really wish other studios, such as Fox and Warner Brothers, would stop trying to recreate the MCU formula around the X-Men and the Justice League (respectively). While WB has hitched their wagon to a dubious, Zack Snyder-led Superman franchise, Fox is barely tapping the X-Men’s potential as everything the Avengers aren’t: despised, misunderstood outsiders struggling to do the right thing despite a system built to exclude them.

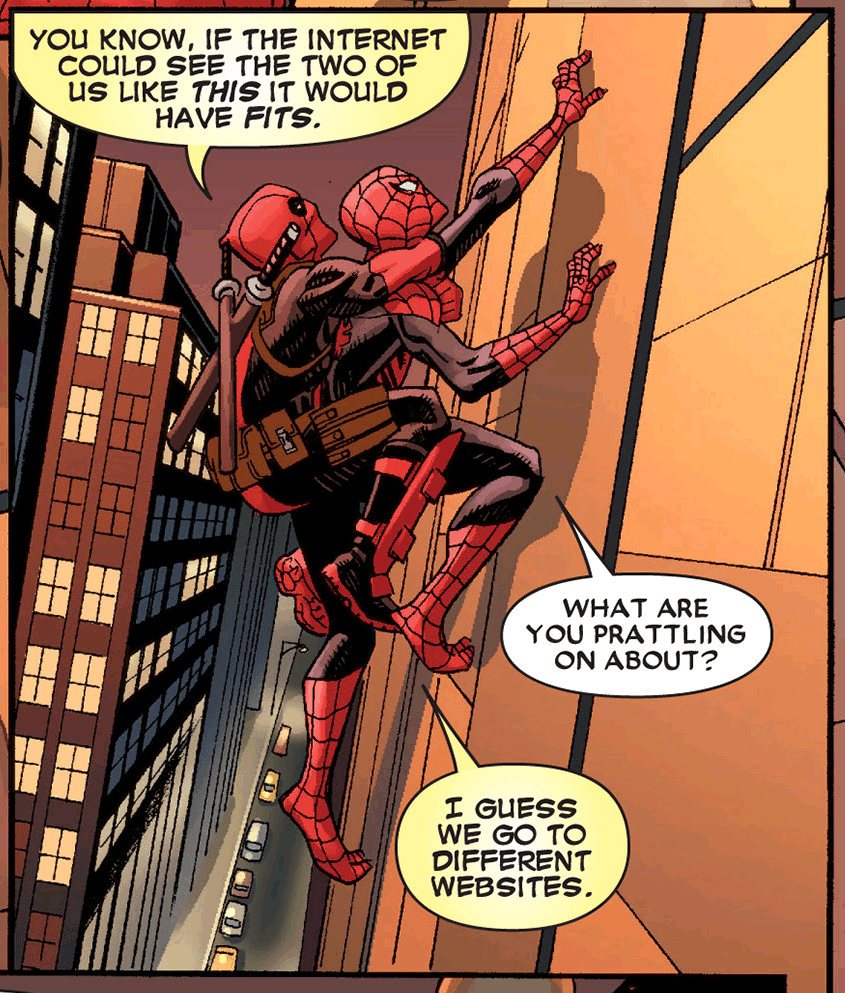

Audiences and critics seem to have loved Deadpool’s refusal to suit up and be a proper hero. But I can’t help but think that Deadpool’s (and Deadpool’s) inherent critique of the X-Men’s heroic aspirations should be aimed elsewhere. He’s suspicious of optimistic do-gooders and alliances. He’s more of an anti-hero than a hero; he’s too violent, too abrasive, and too weird to be a conventional caped crusader. But the same could also be said of a lot of other X-Men characters. Fox is missing out bigtime on an opportunity to create brave, cutting, and subversive new stories about heroism and injustice. I want more movies about cynical, broken-down losers forming their own families, confronting prejudice, and taking potshots at the establishment. Basically, I want the X-Men to do what they were originally written to do.

5. There’s a BIG market for R-rated superhero action… but that doesn’t mean what you might think it means

Superhero violence for grownups! Again, Deadpool’s not the first or best example of the genre. (Blade got there first, but for some reason rarely gets remembered. Cult classic Punisher: War Zone did it fine style. Watchmen adapted the comic book that was supposed to put the nail in the coffin of “Adult Superhero” media, but didn’t have that effect. Daredevil and Jessica Jones are gritty, high-profile hits for Netflix. In 2013, they promised me a smart, stylistic Wolverine movie, but that was pretty disappointing.) But it is the most spectacularly profitable one, and it’s sure to inspire a lot of imitators.

So, if we’re going to imitate Deadpool’s R-rated appeal, let’s make sure we’re imitating the right thing. Deadpool may be nasty and dirty, but it’s not bleak. It’s dark, but it’s darkly funny, and it’s certainly not grimdark. I want to point out that while the movie takes Wade Wilson’s pain fairly seriously, it doesn’t kill and torture his supporting cast. No beloved characters have to die to send him on his fictional journey. The tragedy in his screwed-up tragicomedy comes from being forcibly mutated and tortured, not by fridging the people he cares about. Deadpool’s an amoral, profane, mentally-ill mercenary, but he’s generally not mean-spirited. The thing I liked most about the movie was that it was basically faithful to the chaotic, weird, and loveable personality and tone that originally attracted me to the character. No matter how many people he cold-blooded-murders onscreen, Reynold’s Wade Wilson is a terrible but basically likeable guy. His first instinct is to defend the innocent and follow his heart, even when reality really should have taught him better.

Essentially, Fox has nothing to lose by playing it safe, but apparently they don’t have much to lose by backing the ugly underdog, either. The best case scenario? Deadpool’s improbable success gives Fox a mandate to make superhero media weirder, smarter, and more subversive. Worst case: we get another Avengers clone with more sex and blood. Both scenarios make Fox a boatload of box-office money, so why not get a little weird?