In a padded cell adorned with crudely drawn crosses resides John Trent. Trent has gone so far as to not only decorate his new insane asylum home with crosses but himself as well — they run up and down his mental patient uniform and dance across his very face. Outside the asylum, the world is going to hell, and John Trent knows it. When the kindly Dr. Wrenn comes to talk with Trent, Trent tells him the cold hard truth: “Every species can smell its own extinction.”

Thus begins In the Mouth of Madness, the third and final film in director John Carpenter’s “Apocalypse Trilogy.” The trilogy contained his films The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and this film, released in 1995. The three movies are, according to Carpenter, “in one way or another, about the end of things, about the end of everything, the world we know, but in different ways.” They also share a common inspiration: H.P. Lovecraft. Both The Thing and Prince of Darkness have their fair share of Lovecraftian elements, specifically the theme of helpless mortals dealing with cold, merciless cosmic forces. But it was with In the Mouth of Madness that Carpenter went full Lovecraft, concocting with writer Michael De Luca perhaps the best Lovecraft film adaptation of all time. The irony, of course, is that In the Mouth of Madness isn’t really an adaptation of anything Lovecraft wrote, but rather an amalgamation of the very essence of Lovecraft’s work.

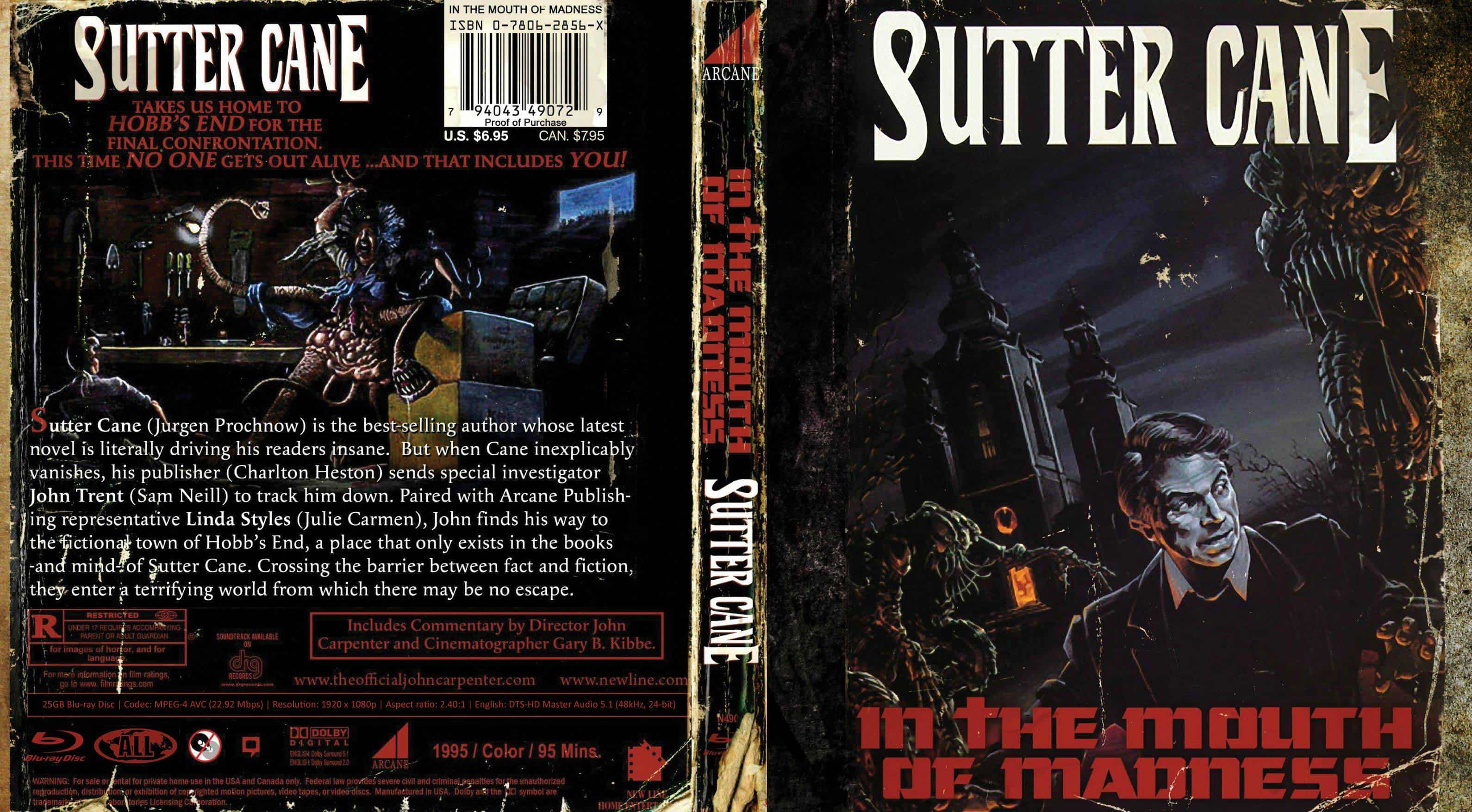

At the heart of it all is a great hook: a famous horror writer has gone missing, and his final novel needs to be recovered. Unfortunately, the novel is so scary it has the power to drive people insane and bring about the end of the world. Sam Neill is the hapless John Trent, who starts his story so assured and cocky, chain smoking as if the concept of lung cancer were some sort of fairy tale. He’s an insurance investigator, and he loves to bust people trying to swindle insurance money. It seems to be the only thing he really enjoys, as we never learn anything else about him besides his job. After finishing up a satisfying job, Trent is attacked in broad daylight by an axe-wielding maniac with bloody eyes who asks, “Do you read Sutter Cane?” Sutter Cane is about to become a big part of Trent’s life: When the famous horror novelist (played by Jürgen Prochnow) goes missing, Trent is hired by publishing giant Jackson Harglow (Charlton Heston) to find out where Cane is, and retrieve Cane’s latest, and possibly final, novel In the Mouth of Madness. Cane’s editor, Linda Styles (Julie Carmen), accompanies Trent as they set out on a journey that will result in madness, monsters, and murder.

The name that keeps getting thrown around In the Mouth of Madness is Stephen King. The fictional New England town that Cane creates, Hobbs End, is very similar to the spooky New England towns of King’s books like Derry or Castle Rock. “You can forget about Stephen King!” Stiles says at one point, declaring that Cane’s books outsell King’s. Even the name Sutter Cane has the same syllables as Stephen King. But it’s Lovecraft that Cane’s work gets its power from. On the few scenes where characters read from Cane’s books, it’s composed of the same type of flowery, archaic prose that Lovecraft was so fond of. And the stories themselves, about hapless mortals driven insane by unbelievable nightmares, are the lifeblood of Lovecraft’s work.

Cane is no mere hack horror writer: his stories are all coming true, and, as a result, he himself has turned into a sort of god. But there are other, older, tentacle waving gods that Cane represents. He calls these beings his “new editors”, and Carpenter only gives us the briefest, creepiest glimpses of them. Part of the reason the monsters remain in the shadows are budgetary — Carpenter just didn’t have the budget he wanted. But the result is far more effective — the fact that we never really get a good glimpse at the creatures who lurk in the shadows makes them all more terrifying. After all, one of the concepts of Lovecraft’s work was that these were creatures who were so unfathomable to see them would drive a person insane. It’s for our own safety that we never get a full glimpse of them, otherwise we might find our minds blasted away into oblivion.

John Trent is not so lucky. He’s pulled deeper and deeper into a story he can’t control, and that loss of control is something that purveys throughout In the Mouth of Madness. Trent is a man who declares “Nobody pulls my strings!” But here he finds that he has been reduced to a fictional creation — a character with absolutely no free will of his own. His attempts to break away end in failure: he tries to destroy the manuscript of In the Mouth of Madness that Cane gives him, but the book always turns up safe and sound. When Trent goes back to Harglow to tell him to never publish the book, Harglow reveals that the book has already been published and that Trent himself delivered the book months ago.

Carpenter made five feature films after In the Mouth of Madness, but Madness is, as of now, his last truly great film (sorry, fans of Ghosts of Mars). It’s not quite a perfect film the way his Halloween is — the chemistry between Neill and Carmen is nearly non-existent, and Carmen, in general, seems a bit wooden through most of her scenes. And the Metallica-tinged score by Carpenter and Jim Lang seems at odds with the material. But Carpenter is still firing on all cylinders here as if this were the last time he truly connected with the material he was filming. You get the sense that he’s finding a certain level of glee in the fact that he’s finally ending the world in a film. In the other two films in the Apocalypse Trilogy, the end-times are small scale and also deliberately vague– The Thing happens to only a small group of men in Antarctica, and it’s never clear if the threat they face has survived and will spread outward, and the demonic force in Prince of Darkness is thwarted at the last minute. Yet with In the Mouth of Madness there can be no question that this is the end, and no one gets out of here alive. When Stiles waxes poetically about the concept of reality shifting, and humanity going down the drain, she muses, “It’d be pretty lonely being the last one left.” And lonely it is, as Trent finds himself one of the few humans in an increasingly inhuman world. Trent has survived the apocalypse unscathed, and while he could continue fighting it and trying to retain his humanity, how utterly lonely that would be. He decides on an alternate route: he goes to catch a screening of the film version of In the Mouth of Madness, directed, in true meta style, by John Carpenter. The film is no mere adaptation of the book, though: up on the screen, Trent sees himself, acting out things that already happened in his life. He begins to laugh. His laughs crescendo into wild peals of maniacal cackling. Before Carpenter cuts to black, we see Trent lean forward, his laughter turning into a sudden moan of pain. He’s changing, becoming something else — something unspeakable. At least it’s better than being alone.