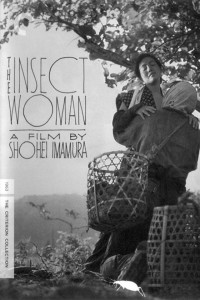

The Insect Woman

Written by Keiji Hasebe, Shohei Imamura

Directed by Shohei Imamura

Japan, 1963

That director Shohei Imamura’s 1963 film, The Insect Woman, can be found in a Criterion Collection box-set called “Pigs, Pimps & Prostitutes” should do more than hint at the content and themes of his work. An auteur dedicated to defying traditional Japanese stories and storytelling, Imamura famously referred to himself as a creator of “messy films,” films that—in opposition to Japanese contemporaries who emphasized taming the animal nature of humanity—explored the immutable wildness of the human condition. And as the only Japanese director to have two Palme d’Or awards under his belt, Imamura’s customary shamelessness verifies his history as one of the leading trend-setters of the Japanese New Wave, a movement dedicated to uninhibited portrayals of social structure and cultural evolution, among other things.

In The Insect Woman, Imamura examines these notions, as he almost always did, through a female perspective, this time to abolish the stereotype of passive victimhood in Japanese women. Instead, Imamura paints a portrait of a peasant farmhand, Tome, who despite her suffering maintains the persona of a sexual, resourceful, and headstrong character determined to persevere.

The film begins on the day of Tome’s birth to a lower-class family in the winter of 1918, to a promiscuous, untethered woman and a mentally retarded father with inappropriate concepts of physical affection. She grows up under the financial chains of tenant farming, but also beneath the gaze of a little stone figure on a shelf in her home—the female “god of the mountain” to whom her family offers tributes in hopes of being blessed with good fortune. From her childhood and beyond, Tome is expected to believe that every circumstance in her life—for better or worse—is part of a preordained destiny designed to keep her in line with social and familial roles. Even when she is raped by her benefactor’s son, Tome’s mother believes the act to be a harbinger of social advancement; if Tome is lusted after enough, she suggests, she might one day get the chance to become her rapist’s wife. Even Tome’s resulting pregnancy brings few alarms; several of the farmhands, after all, are already mothers of illegitimate children.

The film moves forward in time with sudden jerks and freeze frames, mimicking the violent beats of Tome’s life. Faced with the prospect of World War II amidst the culture of abuse she already endures, Tome—played by Sachiko Hidari, whose performance would win her the Silver Bear for Best Actress at the 14th Berlin International Film Festival— is still a wistful soul, eventually keeping a diary through which she reveals her hopes for a better life. Meanwhile, she continues to grasp at any straw that blows her way, sometimes choosing new pains if they could mean a chance at a new future, like when she decides to keep her newborn daughter despite her mother’s urges to “get rid of it.”

Tome is forced to brush the dirt from her knees over and over again, constantly stripped of lowly jobs and sour relationships, so distracted by misery that she accidentally causes the death of a child she had been hired to care for. And when she reaches out to religion to seek salvation, she finds it in a woman she meets at a prayer meeting, but with dire, ironic results. Only when Tome has already accepted the stranger’s help does she realize that the woman is a madam, her new house a brothel, and that she has accidentally sold herself into prostitution.

Still, Tome finally begins to learn the ropes of her bitter existence, eventually moving up the brothel hierarchy until she achieves a sort of economic maturity. Even when her own daughter, Nobuko, betrays her to take over the business, Tome decides to overcome the shock and instead prides her child for displaying such animal-like survival instinct. It isn’t a particularly altruistic outlook on life, but in Tome’s experience, the road to a young woman’s success depends exclusively on her own wills and desires. Not a mountain god’s, not a man’s—her own.

The last scene in the film is perhaps the best depiction of this idea so crucial to Imamura’s work, cycling back to the film’s opening scene of a thorny beetle struggling to climb a mound of dirt. In this, the last look at Tome’s life, the audience watches her become the titular heroine, breaking her sandals and scraping her knees as she climbs a hill of her own. Grunting, cursing, but still ascending.