I spoke with Michael Lacanilao, the creator of the clever Stairwell video that’s been making the Internet rounds, about short-form filmmaking, YouTube videos, and realism. You can support Michael’s project via his Kickstarter page.

Neal Dhand: Your film is, in so many ways, a product of the YouTube generation: short attention spans and immediate payoff. How much of that informed the length and structure of the film? Did you feel that you needed to have a “reveal” or “surprise” early in the video in the event that some impatient viewers might not make it to the end?

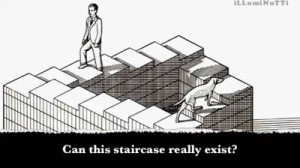

Michael Lacanilao: We actually decided not to worry too much about hooking the audience in early. We simply asked: What would a university science show look like, and how would this particular episode, which happens to feature the endless stairwell, unfold in actuality? The conceit is that a brilliant architect has managed to build this physically and logically impossible structure. Granting that one fantastical element, we wanted to build a world around it that was as close to our (real) world as we could get. We constantly asked ourselves questions like, How would this actually happen? What would a show made by university volunteers look like? How would real people react to this extraordinary thing? And we just went with whatever we believed to be the most truthful answers to those questions, even when that meant there would occasionally be mundane moments and (as some might complain) a “boring” beginning. Sidney Lumet was always careful to make a distinction between “naturalism” and “realism.” And for years, I could not figure out what he meant, or what the distinction was. Because I thought that Dog Day Afternoon was one of the most realistic movies I had seen! But in his writing and various interviews, he always insisted that Dog Day wasn’t realistic, but naturalistic. Then I came to understand it more as I worked on this project. Naturalism entails a responsibility to truthfulness coupled with the intent to dramatize for the audience. (“How would this unfold in reality, and how can we make it interesting?”) Realism, on the other hand, entails a responsibility to truthfulness, with no regard for the audience. (“How would this unfold in reality, whether or not it’s interesting?”) We all typically prefer to see naturalism. But given the nature of this project, I made a steadfast decision to go with realism.

ND: You asked me this question, so I’ll ask it right back: can we imitate (or maybe there’s a better word) a powerful theatrical filmgoing experience via the Internet?

ML: That’s a question that’s interested me since the genesis of the project. Filmmakers in each subsequent generation seem to always be trying to figure out how to best exploit what’s available to them, and today’s generation happens to have the Internet at its immediate disposal. It’s cheap, convenient, and offers the potential to reach a very wide audience. And by now, of course, it’s a platform that’s more than ripe for exploration. But whether or not the Internet can provide a powerful cinematic experience may be a question worth asking, regardless of budgetary constraints. Compared to other art forms like music, dance, sculpture, etc., which have all been around for millennia, the motion picture medium is still, really, only in its embryonic stages and there’s so much more we’re likely to come to understand about it and the depths of experience it can provide. And as young as film is, the internet is even younger. So we’re kind of discovering the answer to that question as we go–and it’s exciting!

ND: Why the mythology? Why not just have this as a one-off video that gets a lot of views and attention?

ML: A myth that goes beyond just the Can You Imagine? webisode opens up an opportunity to build an entire world, existing primarily online, in which this impossible stairwell exists. By the time we launch the myth in its complete form in December, we will already have planted the fake 1997 documentary about the stairwell, various articles and websites that purport to explain how the stairwell works, and clues about its reclusive architect, all for our audience to discover as they dig for online information about this architectural marvel. We’re taking advantage of the scope of the internet to provide as immersive an experience as we can. Just as we had asked “What would a university science show look like if this stairwell was real?”, the question we’re asking for the remainder of the project is “What would the rest of the internet look like if this stairwell was real?” Our goal is not to deceive people, but rather to allow them to get caught up in the excitement and wonder of something extraordinary–like Santa Claus for adults. I think about the wealth of detail put into the world of Avatar, or Harry Potter, or even a Disney theme park ride like the Tower of Terror. I see this project as being done in the spirit of those works in that we just want to immerse our audience in an experience they can get swept up in. The difference is that the platform we’re using is the internet and the experience unfolds through Google searches.

ND: Where did the idea come from? It reminds me of Borges’ labyrinths, just in a modern-day, less genre-oriented form.

ML: It’s hard to say exactly where the idea came from. I remember having a dream about an endlessly looping stairwell when I was 6 or so. I’ve also always found Escher’s work fascinating and used to wonder how cool it would be if his drawings could be recreated in real life. Also, I was 16 when The Blair Witch Project came out, and I’m realizing how big an impact that must have made on this Stairwell Believers myth. I had so much fun poring over their website and all the information pertaining to the mysterious disappearances of the main characters. I’d forgotten about all these things until I recently reflected on how creative ideas take shape and rediscovered some old notes I’d written as a youth. When I began this project 3 years ago, the idea seemed to come together pretty quickly, as though from nowhere. But I guess that’s never really the case.

ND: Do you have plans to incorporate this into some kind of narrative? I’m sure that other people have commented on House of Leaves and some similarities there.

ND: Do you have plans to incorporate this into some kind of narrative? I’m sure that other people have commented on House of Leaves and some similarities there.

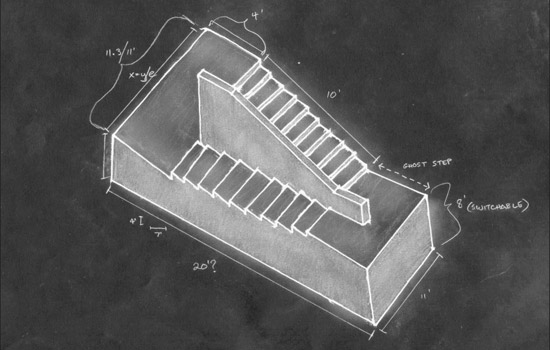

ML: People have mentioned House of Leaves to me! I really have to check it out now. I hadn’t heard of the book, but am intrigued by the comparisons. We are creating a backstory for the stairwell’s reclusive architect, with a few subplots, and a story of how he came to build (and hide) the structure somewhere in the Rochester Institute of Technology’s campus. Clues will be peppered throughout the web, not in narrative form, but as though this thing actually exists, and these events really happened, and this man did disappear. So there might be some discrepancies in the history, depending which website you’re looking at, various theories about what happened to the architect, uncovered sketches, vintage photographs, and even YouTube clips from a recovered PBS-style documentary from 1997 featuring interviews with actual physicists, philosophers, and other academics who are trying to make sense of how this architectural paradox manages to exist. The idea is to execute everything with rigorous realism–it’s just more fun that way.

ND: I know you don’t want to reveal your secret behind the stairwell. Can you talk about the work that went into it? Perhaps some failed attempts to pull it off?

ML: As I wrote the script and storyboarded the shots, I made a conscious effort not to think too much about how, exactly, we would pull off the endless stairwell effect because my main concern was figuring out how the webisode would unfold truthfully and realistically. I didn’t want to compromise realism in order to more easily do a special effect, like, say, incorporating a contrived whip pan because it happened to hide a cut conveniently. When it came to the camera choreography, we asked essentially the same question we’ve been asking throughout the project: How would this happen in actuality? How would the camera operator move, if this thing was actually happening in real time in front of him? Once we answered those questions and choreographed the shots, we considered various ways to make it work including using twins, or multiple cameras, or a rigged set. But it became clear that in order to pull off the effect the way we wanted, we needed to figure out a way to seamlessly edit multiple shots together so they appear to be one long, uninterrupted take. For 6 months, we researched what sorts of tools were available to us, and watched anything we could that tried to do a similar effect–films like Rope, Silent House, El Secreto de sus ojos, and Children of Men. Then for another 6 months, we just experimented. The main problem was that none of the films we watched did the effect exactly the way we wanted to. The common “cheats” were frame wipes, whip pans, or making sure that the character leaves the frame at some point before coming back in. It is very difficult to cut from one shot to another with the same character remaining in the frame the whole time and make it seem like one uninterrupted take, especially when that character is in motion, because things like the folds in clothing and the very nuanced expressions in people’s faces are very hard to match. But we needed shots in which the characters were in frame the whole time. I don’t know if anyone had done this much research in trying to pull a seamless edit off, but I think we learned enough during that one year that we were able to create the shots we had imagined.

ND: What have been your favorite guesses as to how you achieved the effect?

ML: Someone on the Internet came up with very detailed sketches of how he believed we constructed the stairwell, complete with pulleys, lifts, measurements, and various riggings. It was a lot of sketches, too, and well drawn, like he really thought about it! It just looked really cool and I was a little intimidated that he was convinced we built all that.

ND: Do you intend to continue to work in an internet-based short form? If so, why? If not, what are your goals as a filmmaker from here?

ML: My goal, since I was a kid, has been to make feature-length films, so that’s where my sights are set. This whole internet thing just sort of happened in the midst of trying to survive as a filmmaker and being pushed to find the cheapest, fastest, and most convenient platform to work in. I had a teacher that always reminded me that the greatest strengths of a particular medium are those that cannot be duplicated in any other medium, so I’m hoping that this project manages to use the unique characteristics of the web to its full strength–as opposed to simply scaling down the movie-going experience. But it’s been exciting working in web-based form and I’ve learned so much, so of course, yeah, I’d do it again!

— Neal Dhand