Kurt Busiek is probably one of the biggest name in American comics. He started off doing freelance work for both DC and Marvel on titles like Iron Man, Avengers, and The Untold Tales of Spider-Man. In 1993, Busiek joined with superstar artist Alex Ross co-created the classic Marvels mini-series that showed the major events of the Marvel Universe from the perspective of photojournalist Phil Sheldon. From there, he created the long-running, award-winning Astro City series. Kurt Busiek is most notable for his humane approach to superheroes, making characters feel relatable despite their fantastical powers.

In November 2014, Busiek teamed up rising art star Benjamin Dewey for The Autumnlands, a futuristic fantasy series about a world ruled by magic-using animal people that summon a human super soldier from the past to save the disappearing magic. However get more than they were bargaining for. The series is published by Image comics, and after a hiatus is coming back with #7.

Kurt Busiek took a break from his often busy schedule to talk to PopOptiq about The Autumnlands, politics, and rock n roll.

PopOptiq: How did you and Benjamin Dewey meet? What attracted you to his art?

Kurt Busiek: Since Ben’s a member of Periscope Studios, and they’re local, I expect we met at some party or convention somewhere along the line, but I have a terrible memory for faces, so I don’t remember the details. It wasn’t until I was looking for an artist for Autumnlands that I tracked down a number for him and called him up. That’s where our fabled association truly began.

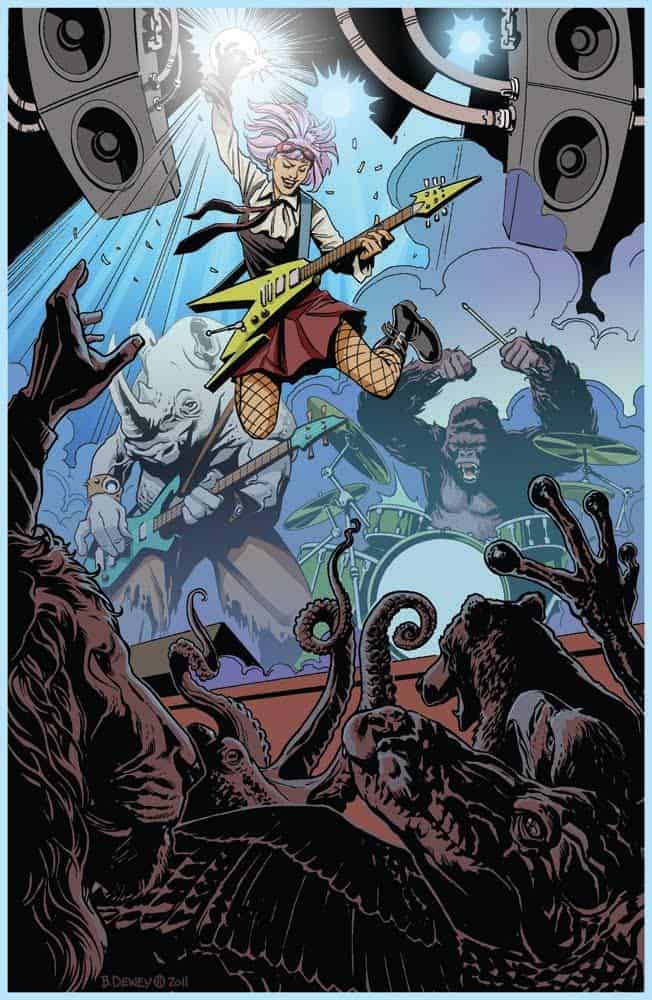

As for what attracted me to his art, it was this image:

I saw that in the Emerald City [Comic Con] art book that year, and thought it was just an amazing piece — charming, energetic, beautifully drawn, and full of great animal drawing with a lot of character. Since I needed an artist for a book that involved almost all that stuff, it piqued my interest. I was curious as to whether he could tell a story well, too, and when I saw a short story he did for a Planet of the Apes annual, I was convinced on that score, too.

So that’s what reeled me in. Then, I found out he’s even better than that and has made Autumnlands come alive like no one else could. So, I’m pretty happy about it all.

PO: How did the series come to be published under Image?

KB: It kinda felt like an Image book to me — unusual, off the normal track, but with the potential for strong visual appeal. A few years ago, when I was recovering from surgery, I took a trip down to California, and one of the stops was Berkeley and the Image offices. We’d been talking, off and on, about me doing stuff there again, so Eric Stephenson, Erik Larsen and I went out to dinner, and I rattled off a bunch of series ideas. Eric liked them all, and Autumnlands was the one I wanted to do first, so…here we are!

PO: What made you want to branch out to the fantasy genre after writing mostly superhero comics like Marvels, Astro City, and Avengers?

KB: I’ve done mostly superheroes, sure, but I expect that’s because it’s the core genre of the American comics industry. I’ve done fantasy before, from the sword-and-sorcery of Conan to the fairy-tale adventure of The Wizard’s Tale, with other books like Arrowsmith in there somewhere. I like fantasy, I read a lot of fantasy so when I step away from superheroes, it’s probably the genre I’m most interested in stepping into.

Plus, I had what I thought was a pretty cool idea, and it was very much an epic fantasy idea…

KB: There are two reasons, really, one an in-story reason and one a behind-the-scenes reason. The in-story reason I can’t really tell you, because it’s something our characters are going to have to figure out over time, and I don’t want to spoil things by blowing one of the big secrets before we’re hardly even started.

As for the behind-the-scenes reason, it’s pretty simple: I’m a big fan of Jack Kirby’s Kamandi, and for years I wanted a crack at writing a Kamandi series someday. But DC didn’t let me. And besides, over time I realized that I’d be much better off creating something new I could do that I’d have full control ove, that would have the things I like most about Kamandi I but in a different way in a series that stood on its own two feet as its own thing.

So, the idea of doing a far-future world of adventure where animal-people were ruling the world was really the starting point, and figuring out what to do with that, how to find a new kind of story in there, that was the building process. But the animal-people were baked right in, right from the get-go.

PO: I also find the comic’s timeline interesting. Normally, we tend to place the fantasy genre in the past and science fiction in the future. You completely flip-flop the order here. Any particular reason why?

KB: Yes, but again, it’d be hard to tell you why without blowing secrets that our characters will discover in time.

I will note that the big breakthrough, while I was playing with different ideas on how to build this series, was reading Jack Vance’s Dying Earth stories, which are fantasy stories set in a far-future, post-technological world, and they were a big influence on the series too. But having decided to do it that way, I did build in a reason why it needs to be that way, and why it makes sense for the hi-tech SF to come before the wild rococo fantasy. I just plan to reveal that when we’re good and ready…

KB: I’m not sure I’d say political squabbles are a major theme of the series — we’ll have to see how things develop as we go. But certainly, there was a power struggle in the first arc, and it’s there both because it’s more interesting to have that going on than it would be if everyone was logical and sensible and tried to pull together for the benefit of all, and also because it’s a very human thing to do. Even in a disaster, there are people who get concerned with who’s going to get blamed and who’s going to look like a hero, which can completely mess up someone else who’s trying to fix problems, and create an easy opportunity for someone who just wants to loot the place.

People jockey for position, and if society is in danger of collapse, it’s not really a case of why they’d do it in that situation — people do that sort of thing _especially_ when the old norms are breaking down and there’s power up for grabs. For some people, they’d rather be captain of a sinking ship than a room steward on a ship that gets repaired. That’s human nature.

And for all that these guys are animals, they show a lot of human nature.

PO: I think that Councilman Sandorst is the worst character in the comic. He is so greedy and self-serving. The only person that likes him is his daughter, Enna, and she has to put up with a lot. Why do you think she still finds good qualities in her father despite his greed?

KB: She may just be polite. Or she may not really understand what he’s doing or why there’s something wrong with it — after all, she’s grown up with him as a father, so it may just seem normal to her. She hasn’t really reached an age where she starts questioning him or rebelling, at least not yet.

As for greedy and self-serving, Goodfoot fits that description, too. But she does it a lot more charmingly than Sandorst does.

PO: The Bison people seem to be set up to be bad guys, but they are starving and live in destitution. The magic users seem to be abusing them for resources. Did you have any real life political allegories in mind when you included them?

KB: Not political allegories, but a few historical precedents, certainly. In some ways, the bison tribes resemble the American Indians of the plains, and in other ways, they resemble serfs in a semi-feudal society though serfs wouldn’t be paid for their efforts. It’s largely a matter of world-building — I knew from early on there would be these great wicker cities floating in the sky, which leads to the question: So where do they get their food from? If they’re up in the air, who’s growing the veggies and raising the meat? That suggested they had servant tribes on the ground below. And given the power imbalance, those servant tribes wouldn’t be treated all that well, which would create resentment, so when the city crashed and the usual power structure was broken, that resentment would boil over.

None of that is particularly allegorical — it’s logical, given these aristocratic wizards who live in castles-in-the-air, that they’re going to have subservient peoples, and they’re probably not going to treat those servants very well at all. After all, animal-people and magic or not, this is a pre-industrial society, and it’s predictable that there’d be class issues and prejudice and racism.

And then on top of that, all that kind of thing makes for a more interesting world, with textures worth exploring. The bison are antagonists, but they’re not bad guys. Our wizard-cities are oppressors — but now they’re in trouble, and it’s not like kids like Dusty and Enna are evil and deserve to be killed, however sheltered and naive they are.

So that gives us a world that feels natural, textured, lived in, just as it would if we were in Arthurian times, and there were aristocratic knights and peasants and so forth.

PO: The morality in The Autumnlands is pretty gray. Heroes and villains can be one and the same. Probably the best example is the human champion Learoyd. He seems to be helping the animal people, but he is ruthless in his tactics. Do you think this has to do with his training, the situation he finds himself in, both, or some other reason?

KB: Yeah, things aren’t simple in Autumnlands, and Learoyd is a prime example of that. The wizards thought they were getting some noble cartoon hero of legend, but what they got is a being who’s every bit as human as they are (maybe more so), full of human failings and strengths and history and reflexive behavior and so on. It’s just not a history or training or culture that fits with theirs.

And that’s one of the questions we wanted to ask early on: Who’s the animal here? The “civilized” animals, who are classist and racist and privileged, or the human who solves his problems by killing his way through them?

So yeah, Learoyd’s ruthless, in great part because he’s been trained to be, and has been yanked out of a big-ass war where survival means killing the other side better than they can kill you. But also, maybe, because he still doesn’t quite believe this is all real, and maybe because he doesn’t see animal-people as fully people, or other things.

We didn’t set up Autumnlands to run out of complications 8 issues in. We want it very messy and human and tangled, because there’s more to explore that way, and we want to have good reasons to explore a lot of this world.

PO: I read the upcoming issue of The Autumnlands, and the action is slowed down to do more world building. Particularly interesting is the concept of hatsas, something that is in the world that magicians can draw from and cast as spells. How did you come up with the concept and will it have a bigger role in the series later on?

KB: Keep in mind that, while Autumnlands has action sequences, but action isn’t the focus. Adventure and exploration (in a variety of senses) are the focus. So I don’t think of it so much as “slowing down the action” as I do “telling the story.” There will be action parts, and there will be lots of other stuff, too.

As far as hatsas goes, there are (as usual) reasons we needed a clear and concrete source of magical energy in this world — for on thing, it’s a work where magic is running out. If there isn’t a power source for it — if you just pull it out of thin air — how does it run out? So that’s part of it. I also wanted magic to be something that can be built, stored, traded, something that master wizards can use better than beginners, but beginners can still buy complicated spells if they have the cash. So being able to store magic, to make spell-structures that can be passed from person to person rather than it just being about knowing a spell and being able to use it over and over, this gave us the kind of magic we needed for this world.

Even a master wizard can’t just use the same spells over and over. Some spells may take a month of preparation, after which they’re stored in a ring or a brooch or something for later. And in battle, he can use that spell…but once it’s been used, he can’t do it again, not until he has a spare month to build that spell-structure all over again.

Some of that is the Jack Vance influence — his magic, in The Dying Earth, had that kind of complexity — and some of it’s a matter of me thinking about magic over the years, playing around with ideas like the Laws of Similarity and Contagion from Pratt & deCamp, or the idea that magic might sorta be like science, if you had to convince electricity and gravity to play along with you, and other strains I think it’d be fun to play with.

And hoo boy, will hatsas play a bigger role as things gets explored. You bet.

PO: I’ve realized how much you like to fill The Autumnlands with political/social commentary. You aren’t afraid of showing off your left-leaning politics (no complaints here). There is your now famous tweet about Captain America being created by liberals in response to recent conservative criticism of the newest Captain America. Winged Victory from Astro City is unashamedly a feminist, and you recently introduced Starbright, a trans superhero. With all the recent complaints about politics in comics, do you see it as your duty and that of other comic creators to take political stances?

KB: I’m not sure that I agree with you about that. Autumnlands isn’t designed to be full of political commentary — it’s designed to be a world full of interesting magic and mystery. But it needs to be a world that makes sense, so that means logic has to come into it, and it needs to be a world full of believable characters, so drama will come into it too. A lot of it is just dealing with repercussions as they arise. For instance, I decided magic was running out because I knew I wanted the wizards to reach back to a time before magic to get this mythic champion back. So why would they need him? Because, um, because they need him to re-do what he did before. Why do they need him to do that? Because magic’s running out. And then, of course, I had to figure out why magic is running out and what revelations that’ll lead to and all, but at least at the start, it’s just about plot and world-building, about working out reasons to have what I want to have happen happen.

And then the first issue comes out, and people go “Hey, this is about a society facing scarcity, so it must be an allegory for peak oil!” I honestly hadn’t thought about oil at all, but that’s a cool resonance, and the idea of scarcity, and how people deal with scarcity, that’s interesting stuff. Do they try to fix it? Do they try to hoard the supply? Do they go to war over it? Do they get crushed by other people jockeying for power? Those are all great questions for an adventure series, aren’t they?

But is it an allegory for peak oil? Am I really suggesting that the way to solve an energy crisis is to reach back in time, get the guy who discovered oil in the first place and have him do it again? I dunno, but that sounds like a pretty bad plan.

I think what I’m doing is telling stories that are about people, and the way people act, even in a fantasy setting where they’re all covered with fur, feathers or scales. And if there are scarcity issues, there are bound to be politics about it, but that doesn’t mean that the political resemblances are the point, rather than the drama and adventure. After all, as you’ve noted, our heroes are pretty variable, morality-wise. So which are the liberals and which are the conservatives? And who’ll win out? And will it be a clean win or an ugly one? Whatever happens, I don’t know that it’ll necessarily map to any real political commentary about the present day.

I’m a liberal, you bet, and I don’t have any great desire to hide it on Twitter. But pointing out that Captain America was created by liberals (a lifelong liberal and a liberal Republican who got more and more conservative as he got older) isn’t a liberal comment, it’s a historical one. I didn’t say it because I want to claim Cap for “my side,” I said it because it’s what happened. I’m interested in comics history, so questions like “Was Captain America created to be conservative” or “How has he been characterized over the decades”? are questions of history. There are people out there who think Cap should be conservative, or should be liberal, and those are certainly political stances, to one degree or another. But the question, “What actually did happen?” is a question of history, and if we’re going to treat it fairly, we put aside personal biases and try to look at the facts.

Anyway, for all that I’m a liberal, I don’t think I write much in the way of overtly liberal stories. I think storytelling is inherently political on a broad scale, because it’s about people making choices, and that’s ultimately political — but in the sense of political parties and the current partisan squabble about who controls the US, I think the characters I write have largely stayed out of that, unless it’s key to who they are, like writing Green Arrow as a knee-jerk liberal or writing USAgent as a law & order conservative. And that’s more a matter of writing them as themselves, getting them “right.”

I don’t have much use for George W. Bush, but when I wrote him in Avengers, I had him say inspiring things, because I thought it was appropriate to the story and the moment for him to do so. Over in The Order, though, he showed up and said a few dopey things, largely because I was co-writing with Jo Duffy. Jo put in the gags and I didn’t think it was appropriate to take them out. But for the most part, my characters don’t talk about their political leanings, they just behave in a way that I think is appropriate to who they are.

Anyway, sure, Winged Victory is overtly a feminist hero; that’s who she is, and we’ve explored that. And Starbright is  a trans woman, but is her mere existence in a story a political statement? If so, then what about the Crossbreed, who are devout evangelical heroes? Is their existence in Astro City a political statement?

a trans woman, but is her mere existence in a story a political statement? If so, then what about the Crossbreed, who are devout evangelical heroes? Is their existence in Astro City a political statement?

a trans woman, but is her mere existence in a story a political statement? If so, then what about the Crossbreed, who are devout evangelical heroes? Is their existence in Astro City a political statement?

a trans woman, but is her mere existence in a story a political statement? If so, then what about the Crossbreed, who are devout evangelical heroes? Is their existence in Astro City a political statement?The way I look at it, they’re people. And I want to tell stories about people, so when the question comes up of whether a trans woman would work well in this story, it’s an idea I’ll explore, as surely as a question about whether there’d be heroes who believe their powers are a gift from God? I’d rather explore humans struggling with the slings and arrows of life than make a political speech.

All that kinda wanders afield from your question about whether creators have a duty to take political stances. For me, I’d say that as a citizen of my country, I’ve got a duty to be involved in the political process, but as a writer, my only real duty is to tell stories as well as I can. I think that human behavior is political in the broad sense even when it isn’t political in an overt elections-and-parties way, so creators’ political natures are going to come through in their stories to one degree or another. But I think that’s a far cry from “duty.”

That said, I think when people complain about politics in comics, what they’re really saying is that they don’t want to see politics in comics that they don’t agree with. If it’s stuff that supports or at least doesn’t contradict their worldview, they don’t see that as political. And when people claim that politics being a part of comics is some recent development, with writers forcing it in when it never used to be there, then I put my historian hat on again, and note that comics have been political all the way back to the Yellow Kid and farther. Whether it’s Cap punching Hitler on a cover and Simon and Kirby getting death threats because America wasn’t in the war yet and a lot of America didn’t want to be, to the anti-Communist stories of early Marvel that include the FF’s origin, Iron Man’s origin, the Hulk’s origin and lots more to Green Lantern/Green Arrow to all those 1970s stories about evil corporations to the 1980s stories about corrupt espionage agencies and on and on and on…comics have always had political issues affecting them, and always will.

It ain’t a new development. And for me, I’d rather have comics written and drawn by people I disagree with (like Bill Willingham on Fables), than to have any point of viewed bleached out of them in the name of inoffensiveness. [Even if you could do that, the very act of choosing what to bleach out is political anyway.]

PO: Are there any upcoming projects from you, Benjamin Dewey, and the other creative team members of The Autumnlands that our readers should know about?

KB: I’m still doing Astro City monthly at Vertigo, with Brent Anderson and Alex Ross. Ben’s plenty busy on Autumnlands, but readers should seek out his Tragedy Series book, and the GN he did with Paul Tobin, I Am The Cat. Jordie Bellaire’s coloring everything and a half, but I’d say people should check out Injection and They’re Not Like Us, for sure. And John Roshell works on Astro City as well, plus Elephantmen and other fine books.

PO: Any fantasy comics past and present, you would recommend reading?

KB: I just mentioned Fables, so I’ll recommend that again — it may be my favorite comic of the last ten or fifteen years. Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, Keatinge and del Duca’s Shutter, Kirby’s Demon, Roy Thomas’s long Conan run, and all the way back to great strips like Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant. American Vampire. Castle Waiting. And tons more, I’m sure, but that’s the first batch of titles that come to mind…

14. The most important question of the day: Queen or Pink Floyd?

While I have friends who were extremely into Pink Floyd, and I like what I heard, I never really got hooked into it the way I did with Queen. So I’m going to have to say Queen.

Autumnlands #7 will be available at local comics stores, Comixology, and the Image Comics website on November 11, 2015.