Jack Shephard was originally supposed to be played by Michael Keaton, and he was going to die in Lost’s pilot episode. After his death, the first to be killed by the smoke monster (that honor ended up going to the plane’s pilot, played by Greg Grunberg), Kate would take over as the leader and primary protagonist. This would have been surprising because it would buck conventions, killing off the heroic white male leader so that the female could take over.

J.J. Abrams and Damon Lindelof quickly changed their minds about Jack’s death, Keaton backed off so that Matthew Fox could become the character we all know, and the rest is history. Kate became just another supporting character in the show’s massive ensemble. The first thing we see in the actual pilot episode is Jack’s eye, and from that point on we stay mostly with him. As the show went on, though, we began to hear many other stories, and the focus gradually shifted away from Jack and towards everyone else. Jack Shephard became a gateway character.

Gateway characters are a risky device for TV writers to use. These are plain, rather boring, typically white and male characters that serve as the main characters in these stories. They are our window into the world of the show, and the other characters that inhabit it. They are where we start off, and perhaps where we ultimately end up (in the case of Lost), but definitely not where we spend all our time in between. They are meant to comfortably usher us into the more complicated and interesting stories that the writers really want us to see. But are they worth the trouble?

The best example of a gateway character is Piper Chapman on Netflix’s Orange is the New Black. This privileged and pampered white woman goes to prison, and the pilot episode is almost entirely concerned with her introduction to it. Taylor Schilling is top-billed in the opening, and we are obviously meant to identify with her confused and scared entry into this cruel and chaotic prison world. That’s the key to the gateway character, the idea that the audience is intended to identify with them as they encounter a strange or new landscape (an island, a women’s prison, King’s Landing). From there, once the character (and us) have oriented themselves, we can begin to learn about everyone else and branch off into their stories. In other words, the rest of the show. Though being an “audience surrogate” is typically part of being a gateway character, it’s also important that this relationship eventually (or quickly) dissolves.

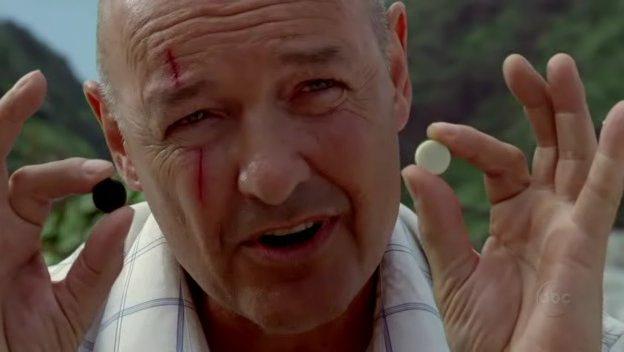

Depending on how you look at it, gateway characters are everywhere. Ned Stark was one on the first season of Game of Thrones, our traditional noble white male hero. We identified with his struggle to survive and protect his family in Westeros, which is why his death in that season’s penultimate episode was so shocking and reverberated so deeply. Now who are we supposed to focus on, Jon Snow?! Ned is an interesting gateway character, though, because once he has served his purpose of letting us orient ourselves within the world of Westeros, the narrative decides to discard him to let us concentrate on all of the other (generally more interesting) characters we’ve come to know. Unlike most gateway characters, Ned doesn’t have a series-long story to be a part of – he’s done what the writers needed him to do, and now he’s gone.

Dale Cooper is a gateway character that quickly reveals himself to be just as fascinating as any resident of Twin Peaks. The show uses him as a gateway into this bizarre town, encountering all of its peculiar citizens and happenings for the first time with a kind of awed curiosity. This is a common start for a gateway character – the visitor in a new town, moving in or taking up an assignment, discovering everything for the first time along with the audience (as TVTropes.org helpfully demonstrates with their entry on the “Naïve Newcomer”). Give David Lynch credit, though, because Cooper is anything but plain or boring – if anything, he’s just as odd and mysterious as anyone else on the show, always speaking to “Diane” and having some pretty crazy dreams.

The list goes on. Nate Fisher in Six Feet Under, Fry in Futurama, even Michael Bluth in Arrested Development and Buffy in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Gateway characters are a fairly common way of letting viewers get used to a new world, or to help a show with a potentially hard-to-grasp concept get around those trappings. Essentially, it’s a way of lightly manipulating viewers into getting invested in the show, and more so to the world of the show than the main character specifically.

This isn’t to say that these shows don’t care about their gateway character. Often they will still receive the most screen time and the most storylines, and the show will continue to revolve around how the other characters interact with them. But writers are fond of telling many stories, and this is one way of preparing audiences to engage with whatever they decide to throw at them. The argument must then be made, however: why not just tell the stories they want to from the beginning? Why not take the bold route and let Kate be the main character (though, in retrospect, they probably made the right call in this case)? Why not have an unconventional lead to set yourself apart rather than relying on a safe choice to hold the viewer’s hand?

I can see the appeal of this approach. What’s more exciting than something boldly and radically different? Our television shows need more female protagonists. Our television shows need more racially diverse protagonists. Our television shows don’t need more of the same. Great, another white male antihero, my favorite.

I can also see the advantages of a more conventional gateway character. Practically, they will undoubtedly more easily appeal to producers and executives, so that they know who to identify with and can confidently sell an entity they are familiar with. As we’ve seen, a show can also deal with their gateway character in creative and interesting ways, from allowing them become as weird as everything else or just killing them off. There are the narrative possibilities these characters allow, as well as the value that comes from “tricking” narrow-minded viewers into caring about characters they may not have otherwise been interested in.

Last year, Orange is the New Black creator Jenji Kohan spoke a lot in interviews about how Piper was that show’s “gateway drug”. Her summary of the phenomenon is succinct and illuminating in this EW interview:

In a lot of ways, Piper was our gateway drug. We wanted to write stories about all sorts of women and their experiences. But it’s very hard to sell a show about women of different colors and different ages and different socioeconomic backgrounds. This way, we almost get to sneak in these amazing characters and amazing stories through this white girl going to prison. With each episode we explore a different character.

Kohan sees it as sneaking them in, after giving us Piper. It may be unfortunate that it’s so hard to sell stories like those, that they do need to be snuck in. But if having to pay attention to Piper’s story is the price we must pay to be able to learn about Suzanne and Poussey and Morello and Red and Sophia, then I’m more than willing to put up with whatever the hell Larry is doing this episode.

– Jake Pitre