“I disappear between these two moments of speech/ self-portrait not autobiography” – Jean-Luc Godard

Never has Godard been so melancholic and comedic in one film. JLG/JLG: self-portrait in December (hereafter referred to as JLG/JLG) is a portrait of an artist, the artist of cinema, at sixty four. Part documentary, part film essay, JLG/JLG is a poignant and tender depiction of Jean-Luc in his apartment in Switzerland. The icy beaches and snowy landscapes depict Jean-Luc entering the winter season, nesting at his desk with pen and notebook, quoting from the history of cinema, literature, and philosophy in the voice-over, intertitles, and the dialogue, pensively ruminating about his place in the history of cinema.

“Self-portrait not autobiography” Jean-Luc tells us and this distinction is important for understanding JLG/JLG. Typical documentary-biopics proceed in this manner: begin with subject’s childhood; list their achievements; pad the film with talking head interviews (the number and length of these depend on the subject matter, for instance, political documentaries include the most compared to other subject matters); include info graphics with quotes from the subject or about the subject; and then simply end with a vague conclusion. “Self-portraiture” is Godard’s take on this storytelling mode, importing his audio-visual tropes we associate with his films into the documentary mode. These include: abrupt use of sound (music cuts out before melodies resolve; and dialogue is played with voice-over sound); the fascination (a post-68 aspect of his cinema) with rural landscapes; and frequent use of quotes in the voice-over and dialogue. These Godardian tropes depict Jean-Luc in December, a specific moment in time and space, as an aging legend. We learn about his thoughts on himself, his image, his legendary status, and his place in the history of cinema. Rather than produce a documentary that catalogs his achievements, we witness his achievements in the form of the film. Self-portrait of Jean-Luc is delivered through cinematic form rather than through conventional documentary procedures.

What does Godard reveal about Jean-Luc? The way he works, thinks, and lives. We don’t get facts but impressions; no talking heads commenting on Godard but fleeting moments of beauty, confession, tenderness, and comedy, bringing us closer to the reality of Jean-Luc but never entirely presenting that reality. This is exactly what Godard’s post-68 cinema is all about: creating new types of images because the old ones have been co-opted by late-capitalism. Self-portraiture for Godard means using these new types of images in the creation of his self-portrait of Jean-Luc. Not biography but a picture.

In this picture contains staged sequences involving a woman interviewing for an assistant editor position and a maid (in a skimpy outfit) cleaning Jean-Luc’s house. Self-portraiture involving creating fictions to delivery truth; foregoing the desire to depict reality, Godard recreates moments from Jean-Luc’s working life. These fictional moments become another facet of the self-portrait. Using staged sequences in documentaries is certainly not a new technique in documentary movies or in cinema more generally. Orson Welles used similar staging techniques in F for Fake (1973) and Filming Othello (1978) as did Abbas Kiarostami in Close-Up (1990). In JLG/JLG these staged moments emphasize the importance of editing for Jean-Luc as a director and the importance of young, beautiful women for Jean-Luc’s cinema. The sexy maid in JLG/JLG dusts his shelves full of books and movies referencing Jean-Luc’s encyclopedic knowledge of literature, philosophy, and cinema.

Not only does Godard reference Jean-Luc’s immense knowledge of cinema but he also references Jean-Luc’s films. The exterior shots are reminiscent of those used in Helas pour moi (1993) (the same locations were most likely used in each film); lines from the voice-over and dialogue reference 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (1967) (“2 or 3 Vietnams creates…2 or 3 Americas); the table full of postcards recalls the postcard images from Les carabiniers (1963); images from La Chinoise (1967) play on a TV in one scene while Jean-Luc questions to the depiction of class conflict with images. And there are certainly many more in the film that only the most astute Godard cinephiles would catch. What these references do is add another layer to the self-portrait which is past cinema, specifically Jean-Luc’s past work. Jean-Luc questions his own works and strategies for producing images confessing to us his uncertainty about his work. Modesty and constant self-criticism are another shade of color in Jean-Luc’s self-portrait, hence the voice-over delivered by Jean-Luc quoting Wittgenstein “might we say, that where doubt is lacking, knowledge, too, is lacking?”.

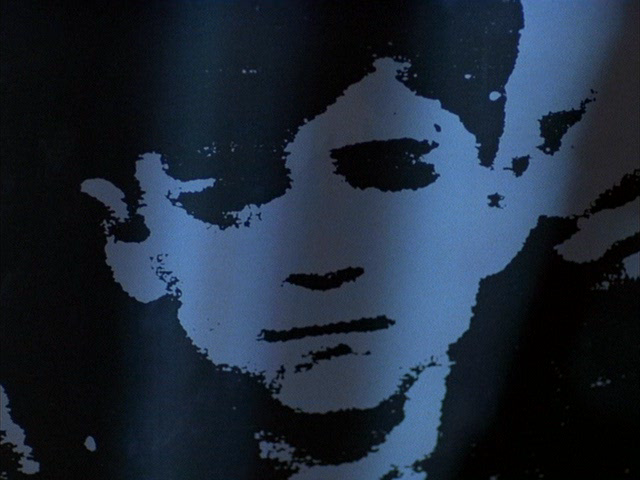

“I disappear between those two moments of speech…” reads Jean-Luc in JLG/JLG. The “I” who speaks about me disappears. Jean-Luc is the subject of this film by Godard but between these moments (Jean-Luc and Godard) JLG disappears hence why Godard created a self-portrait of Jean-Luc. The self-portrait is the trace of JLG on film and video and in the soundtrack. Self-portraiture is then always about producing a trace because it is impossible to produce an individual is not possible with images. Between those moments of communication, taking oneself as the object of their creation, can only be an autobiography or a self-portrait.