You may have seen recently that Joss Whedon “endorsed” Mitt Romney for President saying, “You know, like a lot of liberal Americans, I was excited when Barack Obama took office four years ago. But it’s a very different world now. And Mitt Romney is a very different candidate. One with the vision and determination to cut through business-as-usual politics and finally put this country back on the path to the zombie apocalypse.”

Joss Whedon is absolutely right to invoke zombies in a political discussion, because zombies are the most political of monsters. Or to put it another way, Zombie films are the most political of all horror films.

…

…

…

Wait. What?

Let me explain.

Roger Ebert, in his review of Zombieland, wrote about Zombies:

Vampires make a certain amount of sense to me, but zombies not so much. What’s their purpose? Why do they always look so bad? Can there be a zombie with good skin? How can they be smart enough to determine that you’re food and so dumb they don’t perceive you’re about to blast them?

It is exactly the purposelessness of Zombies that make them perfect for political commentary. That and the lack of real rules regarding Zombies. No matter how slavishly fans cater to the rules laid down by George Romero, there are huge variants in the walking dead: there are non-eating Zombies, omnivores who will eat anything and picky eaters who only want specific food like brains; some are dead, some are dying and some are alive; some can be killed like any human, some can only be killed in specific ways, some can’t be killed; some zombies aren’t contagious, some are insanely contagious (one drop of blood to the eye and you turn instantly) and some Zombie viruses take a long time to turn their victims, amongst many other variants.

That variation allows filmmakers to use Zombies as ferocious (and hungry) political commentary, whether it is George Romero commentating about the emptiness of our shopping-mall culture in Dawn of the Dead or Danny Boyle simultaneously skewering PETA and the military in 28 Days Later.

That variation allows filmmakers to use Zombies as ferocious (and hungry) political commentary, whether it is George Romero commentating about the emptiness of our shopping-mall culture in Dawn of the Dead or Danny Boyle simultaneously skewering PETA and the military in 28 Days Later.

The other secret to Zombie films is that Romero built his Living Dead series on the intersection between the Haitian Zombies legends and the Cold War paranoia alien invasion films like The Thing and Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

If you look at The Thing and Invasion of the Body Snatchers both films are about alien plants who eat (or I suppose compost) humans in order to create duplicates who try desperately to pass as human. When their deception is uncovered, they react with violent rage. The last minutes of Invasion of the Body Snatchers have the hero desperately running from the not-quite humans assembled as a mob. The genesis of the shambling Zombie horde.

To prove that Zombie films are political commentary, here are six of my favourite Zombie films along with the political lesson that they teach.

6. Mulberry Street (2006) imdb

6. Mulberry Street (2006) imdb

Directed by Jim Mickle, screenplay by Jim Mickle and Nick Damici

Zombie Classification: Live, contagious, mutated rat-zombies, omnivores, hard-to-kill, fast, mob

This apocalyptic vision of New York island being over-run by plague rats and the rat zombies (or were-rats, you pick) that result from the rat bites, focuses on one New York neighbourhood (Mulberry Street) and one building on that street. Drama is heightened by compressing time and by compressing space. By tightening the screws on where the film takes place, we allow ourselves to extrapolate the destruction of this one neighbourhood, the destruction of this small world, into the destruction of the world entire.

The two main characters of the story are an aging boxer and his daughter who has just returned from Iraq.

The film borrows heavily from the film noir trope of the war veteran returning home from the war only to find that home no longer exists, or that if it does that it can no longer exist for her, because the veteran’s scars both internal and external prevent her from making a real return.

The building that the soldier’s father lives in is being yuppiefied, meaning that her neighbourhood is being destroyed as she returns. The film then takes the idea of this slow, gradual destruction of her neighbourhood and makes it literal as the rat zombies destroy the already doomed building and its inhabitants.

And you can see why the soldier desperately wants to return, because her neighbourhood is the kind of place which accepts the scarred and the broken. Everyone in the building is an outcast, battling against some kind of handicap, from an over-the hill boxer to a single mother, from a moody and misunderstood teenager to a disabled WWII vet who needs oxygen to survive, from a man confined to a wheelchair to a man imprisoned in silence by his hearing and so on.

In most horror films, the building’s janitor would be a stereotyped villain – in the pockets of the developer – but instead, he is a member of the community, ribbed good-naturedly by his neighbours for the building’s disintegrating infrastructure, but also making the necessary repairs as quickly as he can in a losing race as the building disintegrates faster than he can repair it. (And tellingly, he is bitten trying to make repairs.) He is one of the early victims of the plague, but also tellingly, when he attacks his neighbours, they choose to lock him up rather than kill him.

The only characters in the building that might qualify as not-outcasts are the Yuppie family who desert the building at the first sign of trouble, when all of the other outcasts rally together.

Political Lesson: The danger of gentrification is that you sacrifice the history and the historical strength of a neighbourhood in return for a higher tax base.

*****

Directed and written by Adam Green

Zombie Classification: Dead, non-contagious, loner, impossible to kill

There are those who would argue that Victor Crowley, like Jason Voorhees and WWE’s The Undertaker, is not in fact a zombie. There is a longer argument that I could indulge in, but side-stepping all of that allow me just to point out that they call it “The Zombie Sit-Up” for a reason.

Hatchet makes it onto this list partly as a result of odd timing that gives the film an unexpected political resonance. It was the last film shot in New Orleans before Hurricane Katrina, adding a political frisson to this “Old School American Horror” tale of a group of tourists who take the wrong turn during a swamp tour and run into a ferociously angry Victor Crowley – who like all Angry Dead takes his revenge on the living. The film reminds us that in Louisiana, since you hit the water table well before you dig down six feet, you don’t so much bury the dead as temporarily submerge them.

The swamp that destroyed the credibility of George W. Bush was not the morass of Iraq and Afghanistan as much as Katrina which pointed to the hypocrisy in Bush’s message. What was the point of restricting freedoms in the name of safety, if you can’t deliver on your promises of safety? The chaos of the Bush administration’s ineffectual response to Katrina proved that they would have been equally ineffectual in the face of another terrorist attack, which put their entire platform into question.

Compare Bush’s reaction to Katrina with Obama’s reaction to the earthquake in Haiti or the way that FEMA seems prepared for Sandy.

Political Lesson: You can’t prevent disasters, but you will be judged on how you respond to them.

*****

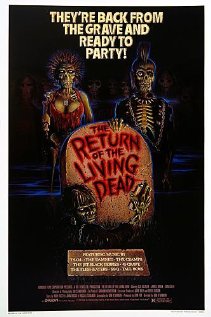

4. The Return of the Living Dead (1985) imdb

4. The Return of the Living Dead (1985) imdb

Directed by Dan O’Bannon, screenplay by Dan O’Bannon, book by John A. Russo, story by Rudy Ricci and Russell Steiner

Zombie Classification: Dead, contagious, picky-eaters, hard-to-kill, mob, talkative

The first great Zombie comedy is surprisingly subversive. The Zombies are created as a result of an Army experiment gone wrong. The Army not only knows of the possibility of a Zombie epidemic they actually have a horrifying contingency plan in the event of an accidental spill of their Zombie-creating toxic goop. (As opposed to say not making the stuff in the first place.)

Meanwhile, the Zombies mock the crumbling infrastructure of the U.S. of the 1980’s, “Send More Cops!” “Send More Paramedics!” The Zombie variation on “911 is a Joke.”

If you look at Rudy Giuliani’s successful career as New York Mayor, one of the very simple things that he did was to hire more cops, which surprise! surprise! resulted in a reduction of the crime rate. Mind you he was able to successfully expand the N.Y.P.D. because others (including Giuliani as District Attorney) had cleaned up the police force from its brutal, corrupt and inefficient Serpico days. The N.Y.P.D. of the 90s was still capable of corruption, brutality and inefficiency, but it was more the exception than the rule.

Political Lesson: Beware of military adventures. Invest in infrastructure. More cops help reduce crime. More paramedics help save lives. More fire-fighters help stop fires.

*****

3. End of the Line (2007) imdb

3. End of the Line (2007) imdb

Directed and Wriiten by Maurice Devereaux

Zombie Classification: Live, non-contagious, die like humans, mob, Zombies-by-proxy

Zombie-by-proxy is a lovely term that I found about thanks to Jim Emerson’s Scanners blog. It refers to humans who act like Zombies, the primary example being George Romero’s The Crazies – or the Breck Eisner remake. The Zombies in 28 Days Later – plague victims who starve to death when they run out of victims – are essentially Zombies-by-proxy.

The End of the Line give us what I described on its release as “Compassionate Zombies”. The monsters of the films are religious zealots on a subway who receive a message that the end times are here and begin slaughtering the non-believers on the subway to spare them from the horrors of the apocalypse foretold in Revelations. (Using knives because the Bible doesn’t talk about guns.)

There is certainly room for a movie about the dangers of Muslim religious fanaticism, but Devereux makes the allegory more immediate (and more universal) by tackling Christian fanaticism.

Have you ever sat down on a bus or a subway besides one of those polite, clean-cut religious missionaries, with their clean white shirts and perfectly creased black pants and their straight black tie and that spooky little black name tag with their name and rank? They are a little bit creepy aren’t they? And isn’t one of the reasons that they are a little scary, the fact that they have a rank – implying that they are organized like an army and that they take orders. (“Don’t be insolent with me,” barks one of the film’s villains, “I outrank you!“)

What if (asks End of the Line) they did get orders? What if their pagers or cell phones went off one day with an order? And what if that order was to kill everyone who was not a member of the Church?

(Just to be clear the religious fanatics of the film are NOT Mormons. The film gives us equally polite, equally well groomed, brown-shirt wearing members of a fictitious Christian faith.)

Since the victims of the film are trapped deep underground, we are trapped with them in claustrophobic dead ends, and like the film’s victims, we are uncertain whether this is an isolated phenomenon or, as the compassionate monsters of the film claim, part of a Universal Armageddon. Isolated and desperate, the well-drawn characters of the film have no choice. As Jim Mickle of Mulberry Street said, “It’s a Zombie movie. Zombies chase you and you run.” This is as true of religious Zombies as it is of the undead.

The film is paced like a Zombie film only the killers are all too human, and the film allows us to see the whole gamut of faith at work: the true believers, the doubters, the lapsed, those who joined to satisfy loved ones and those who merely profess belief. The worst of the fanatics is also in a weird way the most reassuring. “I am not sure if I really believe in this stuff, but I am trying to keep an open mind,” he confesses to one of his victims. He is the worst of the villains, because he kills (and threatens rape) even though he does not believe that he is getting orders directly from God, but he is also a little reassuring because we can understand him, he is the traditional bad guy from hundreds of horror films. The rest of his tribe are a little harder to categorize.

It would be so much easier if these were just faceless brainwashed monsters, drooling undead. What makes this film so God Damned terrifying is that the compassionate monsters truly believe that by killing those not of the church, that they are sending them straight to God, saving them from unbelievable anguish and torment in the final days.

Political Lesson: You can’t win an argument with a zealot. It’s pointless to even try.

*****

2. Zombieland (2009) imdb

2. Zombieland (2009) imdb

Directed by Reuben Fleischer, written by Rhett Resse and Paul Wernick

Zombie Classification: Dead, contagious, omnivores, hard-to-kill, mob

This spiritual heir to The Return of the Living Dead was dismissed on its release as a Hollywood version of Shaun of the Dead, but there is a lot more going on here. The film takes a quick shot at our Fast Food Nation claiming that the Zombie epidemic started with a burger contaminated with Mad Cow Disease.

The film follows a survivor, Columbus, who blunders into a make-shift family and then finds himself conflicted between his need for a family connection and his rules for surviving a Zombie Apocalypse, “The first rule of Zombieland: Cardio.” While these rules for survival do keep Columbus alive, they also prevent him from living. To really live and connect with others, he must learn to break the rules that keep him alive.

Quick awkward confession about Canadians. Our favourite President pre-Obama was Jimmy Carter. We liked him because he was honest, polite and seemed like too nice a guy to be President. (We feared Reagan, thought Bush Sr was a hypocrite, knew Clinton was a hypocrite, knew George W was an idiot.) Now of course, all of the reasons that we liked Jimmy Carter as President were the reasons that the U.S. voters considered him a failure as a President.

So, as a Canadian who likes Obama because he is honest, polite and seems like he is too nice to be President, I fear that Obama will be considered a failure like Carter unless he learns that while the velvet glove is fine, sometimes the iron fist may be necessary especially with his political enemies.

In other words…

Political Lesson: Sometimes to survive you need to break the rules, or to quote Tallahassee, “Time to nut up or shut up!”

*****

1. Night of the Living Dead (1968) imdb

1. Night of the Living Dead (1968) imdb

Directed by George A. Romero, Written by George A. Romero and John A. Russo

Zombie Classification: Dead, contagious, omnivores, hard-to-kill, mob

The Grand-Daddy of them all obviously and as I mentioned up above built on the intersection between the myths of the Haitian Zombies and the cold-war paranoia of The Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

One of the reasons that Romero’s classic still speaks to us, is still relevant more than 40 years after its release is that it gives no easy answers. The film can be (and has been interpreted) as ferocious political criticism on variety of topics.

To quote Brian Eggert from Deep Focus Review

Commentators interpreted the film’s zombies as capitalists, racists, counterculturalists, and extremists, to name a few. The cannibalism was described as humanity’s irrational compulsion for violence—our seemingly imbedded need to destroy one another. In total, the film was commonly explained as a protest against the current Vietnam conflict, a critique of the media, cynicism toward familial and governmental establishments, and a severe blow against civil defense. Which of these readings was correct? All of them. None of them.

The other reason that the film still speaks to us is its hero, Ben Hanser played by Duane Jones. Romero has always insisted that he cast Duane Jones as Ben Hanser because he was the best actor that he knew who wanted the part; in other words Duane Jones got the part because he was the most qualified person for the job.

The other reason that the film still speaks to us is its hero, Ben Hanser played by Duane Jones. Romero has always insisted that he cast Duane Jones as Ben Hanser because he was the best actor that he knew who wanted the part; in other words Duane Jones got the part because he was the most qualified person for the job.

And there is very much a sense in the film that Ben Hansen is the hero not because he is a black man or because the filmmaker is trying to make a point. Ben Hansen is the hero because he is the hero, point finale. Compare this to the Sidney Poitier films of the period where his films always seemed on the verge of congratulating themselves for casting a black man in the part or for making a bold statement about civil rights.

Sadly, in much of the commentary and reaction following Obama’s election and inauguration there was the same sense of Poitier like self-congratulation on the election of the first Black man to become President. The first political lesson that we should take from Night of the Living Dead is the hope that if Obama is re-elected next week, it will be because he is the most qualified candidate, or to quote paraphrase Martin Luther King Jr. “[He] will not be judged by the color of [his] skin but by the content of [his] character.” America finally catching up to Romero, 40 years after the fact.

This, by the way, is not to argue that Obama was the least qualified person for the job in the 2008 election. Just that from the way everyone talked about his win after the election and during the inauguration, the fact that the Obama/Biden ticket was an obviously better choice than the McCain/Palin train-wreck was immediately forgotten as everyone indulged in a frenzy of self-congratulation for finally healing the racial divide.

The other political lesson from Night of the Living Dead is the one that I hope we do not repeat. Romero’s film is about the rise of a hero during a time of great crisis, who is destroyed by his heroism.

Like many people, I have faith that Obama can be a Great President. I only hope that if he rewards our faith in him, that we will receive a better reward for his heroism than Ben Hanser did at the end of Romero’s Night of the Living Dead.

– Michael Ryan

[vsw id=”6TiXUF9xbTo” source=”youtube” width=”600″ height=”400″ autoplay=”no”]