Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck

Directed by Brett Morgen

USA, 2015

It was 2004 and I was fifteen years old when I read Charles R. Cross’ Heavier than Heaven. I remember finishing the last chapters, sprawled on the floor of my family’s cottage as I cried so hard I started to dry heave. At the time I was unaware of the controversy that surrounded the adaptation, both in how Cross took liberties in certain facts (some information was later disproved, or at least not substantiated) and the decision he made to create what was ultimately a fictional take on Kurt’s final days up until the point he killed himself. Like many teenager before and since, Kurt Cobain represented a romantic and ultimately tragic figure to look up to – for better or for worse.

Much has been made of the romanticization of Kurt Cobain’s life and death over the past couple of months, coinciding with the anniversary of his death on April 5th and the release of a new documentary of his life, Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck (dir. Brett Morgen). Billed as the “authorized” documentary, it is as much a response to films that preceded it as it is to the angry fandom that have deified Kurt as a rock god. The film does not skirt around the romance of his vision, portraying him as a troubled genius plagued by insecurity and drug addiction – yet the film reveals quite plainly the failures of testimony to paint a complete portrait, often allowing images, words and fallacies to speak for themselves.

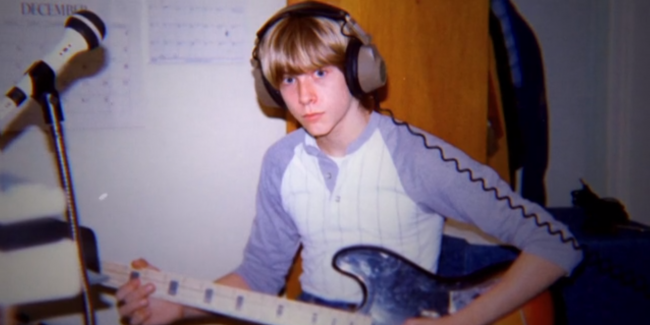

The film is constructed mostly through Kurt’s own words and experiences – there are talking heads, but they are kept mostly to a minimum. Home movies, animated sequences based on real events or Kurt’s own drawings hold more privilege than the interviews of family, friends and lovers. This allows us to really see the world from his point of view, and reveal the ultimate problem with testimony. Who are we to trust when we all filter life through our own experience?

Images hold a lot of power in a society, and we are more inclined to trust an image than we are words. Home movies of an obviously strung out Kurt and Courtney playing with their daughter Frances who won’t stop crying speak levels to the nature of their drug abuse. These scenes are difficult to watch, and plainly contradict the more romantic vision of a couple who would do anything for their child – short of quitting drugs. One of the peculiarities, as well as strengths, of Morgen’s film is how the point of view changes from being in the mind of a troubled child to taking an outside perspective as he grows up into a troubled adult. Perhaps this is part of the nature of fame, in spite of having access to home movies, Kurt becomes increasingly aloof and troubled and does not make a good filter. Perhaps this is Morgen’s way of distancing himself from the romance of the troubled addict genius.

The film’s final act is a grand departure from Cross, as Morgen purposefully elects not to guess at what happens to Cobain in his final days. Courtney Love is really the final filter. As Courtney Love admits that Kurt’s first suicide attempt in Rome was prompted by her THOUGHTS of cheating on him (she is adamant about not even making a phone call, but he was so sensitive and so aware that he “knew”), the film concludes on the Nirvana MTV unplugged performance of Leadbelly’s Where Did you Sleep Last Night, a haunting chant of infidelity.

It’s difficult not to draw conclusions, but perhaps they are not as obvious or as damning as they initially seem. The film highlights Kurt Cobain’s obvious instability but also his violent aversion to humiliation, and perhaps just a perceived slight like infidelity was enough to push him over the edge. Does that make him a hero, or a madman? If he was right and she did cheat on him, does that make his actions more or less understandable? Ultimately, there is no room for moral judgement when someone decides to take their own life and that is difficult for people to really accept. Condemnation or mythologization is easier than confronting the fact that suicide does not offer answers to the questions we want to ask. This lack of closure is unfortunately perceived as romantic as it is infuriating.

Montage of Heck is a great film in part because it does not try to offer too many answers. The problem with accounts of Kurt Cobain’s life thus far have largely been tied to people “filling in the blanks” and treating Kurt Cobain as if he were some literary character and his actions could be interpreted with linear cause and effect interpretations. Brett Morgen does sway in some directions, but mostly due to overwhelming evidence (Kurt was terrified of humiliation – he wrote about, his friends and family were aware of it) but we still feel an appropriate amount of uncertainty in the conclusions that the film makes, because even with a wealth of journals, home videos and second hand interviews stepping into someone else’s mind remains an impossibility.

I am a lifetime away from the teenage girl lying on the floor crying over Kurt Cobain, but I am reluctant to let go of that feeling. The reactions to Kurt Cobain’s death, now over twenty years later have taken on new “enthusiasm”. We live in the age of the thinkpiece, where somehow in spite of having decades of reflection people are quick to make easy prescriptions on what that death means, and how we should react. While there are certainly exceptions, this prescription of judgement is unfortunately symptomatic of a society that is uncomfortable with uncertainty.