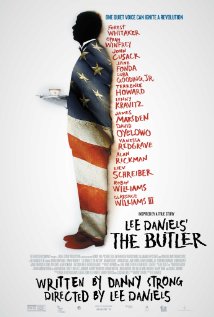

Directed by Lee Daniels

Written by Danny Strong

USA, 2013

Lee Daniels’ The Butler is an intensely silly film, but all things considered, it’s silly for unexpected reasons. A movie that offers up the image of John Cusack playing President Richard Nixon, with the only distinction between Cusack’s normal visage and his Nixonian veneer being a Pinocchio-like nasal extension, should have its silliness all sewn up in such goofy celebrity casting. But instead, what makes Lee Daniels’ The Butler almost entertainingly ridiculous is less the eclectic, deliberately weird cameos and more a flat, sappy, and inconsistent-to-the-point-of-being-schizophrenic script that very badly wants to tie its title character to Important Events of the 20th Century without fleshing said character in at all.

Forest Whitaker plays Cecil Gaines, a kind young man who becomes one of the butlers at the White House in the mid-1950s after rising from the ranks first of living at a cotton farm and watching his father get killed for trying to stop his mother from being sexually violated, then to working as a servant in a swanky Washington, D.C. hotel. For 30 of the most fraught and tense years of the 20th century, Cecil works as a butler to presidents as diverse as Dwight Eisenhower (Robin Williams, because why not), Lyndon B. Johnson (Liev Schreiber, because why not), and Ronald Reagan (Alan Rickman, because…you get the picture). Cecil handles the intensity and unpredictability of his high-level job with infinite calm—though he’s never involved directly, he often coincidentally serves these Presidents as they talk about particularly memorable part of their respective administrations, from the Little Rock school segregation to apartheid in South Africa. However, at home, he deals with a challenging family situation, as his wife (Oprah Winfrey) relies heavily on alcohol to deal with his constant abseces, and his eldest son (David Oyelowo) becomes heavily ensconced in the civil rights battle of the 1960s.

So, yes, there’s a lot going on in Lee Daniels’ The Butler, directed by…well, take a wild guess. In fact, there’s far too much going on, especially considering that this film is just “inspired” by a true story; do a little digging and you’ll find out that the inspiration is razor-thin: there was an African American butler who served in the White House from the 1950s to the 1980s, and that is about where the similarities end. The real butler’s name wasn’t Cecil Gaines, nor did he have two kids, one of whom served in Vietnam. (Cecil’s youngest does here mostly to provide the audience another cinematic signpost to clue us into the rough time period where certain scenes are set.) Now, granted, verisimilitude is extremely far from Daniels’ mind (nor is it a guarantee of quality), as evidenced from the first 1952-set scene, when we meet Cecil and his kids. Oyelowo is 37 years old in real life, and in this moment, he’s asked to play a 17-year old with pretty much no makeup. There’s no hiding the two-decade gulf, and neither Daniels nor Oyelowo attempt to obfuscate. And when men like Williams, Schreiber, Cusack, Rickman, and James Marsden (as JFK) walk onscreen, it’s kind of fascinating to see how similar they look to the way they do in real life. The façade is more important than the reality in Lee Daniels’ The Butler.

Honestly, the moderately self-aware nature of this movie is what makes it even fitfully enjoyable. The script, influenced by a 2008 Washington Post article and written by Danny Strong of Recount and Game Change, is less a cohesive story and more a series of cinematic postcards meant to offer a “We Didn’t Start The Fire”-esque view of the Baby Boomer era. Cecil floats through history, much like his son Louis does. Some of the episodic pieces of Lee Daniels’ The Butler work more than others, even if they don’t make sense in the whole. Take, for instance, Winfrey’s character; her performance, it seems, is meant to evoke nothing short of Elizabeth Taylor’s turn in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf: a big, boozy, blowsy, larger-than-life woman identified mostly by her carnal lusts, all the more striking because of how frequently rejected she feels. For a few scenes, she seems frustrated that Cecil has become unable to separate himself from his work; next, suddenly, she’s spurning her sleazy neighbor (Terrence Howard), with whom she’s apparently been hooking up in the past. Plot points do not arrive naturally in Lee Daniels’ The Butler; they are announced and immediately disposed of.

And for a movie with such a massive cast of characters, Lee Daniels’ The Butler is not one full of striking or arresting performances. Oyelowo, in spite of being forced to play a character from age 17 to well past middle age, is strongest among the ensemble, emphasizing that while Louis and Cecil may be vastly different men, the younger man has inherited his father’s calm, even in highly stressful situations. Whitaker isn’t bad as Cecil, though the vast difference between how he acts at the White House versus how he acts at home–deliberately so, as he’s instructed early on to have “two faces” in life–is sometimes so startling that it’s off-putting. The various actors playing real-life figures do their able best, but are on screen for, respectively, a handful of minutes. Schreiber, despite being given a cartoon version of LBJ, is most winning, even piled under scads of facial makeup.

As pure camp melodrama, Lee Daniels’ The Butler works a fair amount of the time. It’s hard to pin down the authorial intent, however; Strong’s script is so ham-fisted and heavyhanded, so misplaced in its earnest nature. Thus, Daniels’ attempt to emphasize how unreal this supposedly clear-eyed, uber-liberal view of American history is turns the film into something strange. This film is never boring, that much is true, though at 132 minutes, it’s a wee bit overlong. Never boring, though, translates sometimes into jaw-dropping, as in a scene where Winfrey makes Whitaker change into a new outfit that’s identical to hers right before they get a terrible piece of news, all while Soul Train blasts into the background. You may walk into Lee Daniels’ The Butler, wondering what it’s going to be about, what its intent is. But it’s too inscrutable, too scattered to pin down, a choice that doesn’t serve it well.

— Josh Spiegel