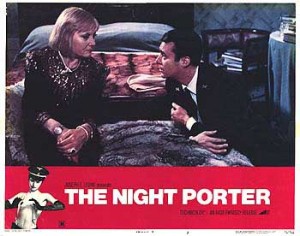

The Night Porter (1974)

Directed by Lilliana Cavani

Italy – 118 min. Color

Criterion Spine # 59

“History is present,” writes E.L. Doctorow and its presence weighs heavy in every frame of Lilliana Cavani’s The Night Porter. Here is a film that is about war, but is not a war film, about sex that is not erotic and about redemption from those who do not seek to be redeemed. It is a film about hunger at its most primal, that fierce desire for survival that eats away those who have yielded to it. It is a difficult film to watch.

The theme of the movie, one of them, is the transformative power of war. You never really think about war in that light because so much emphasis is put on what has been destroyed, especially when we talk about World War 2 and the monumental amount of life lost in its wake.

We meet our main characters twelve years after the end of that war and we see how quickly the facades they’ve built in peace time crumble. Max (Dirk Bogarde), is the eponymous night porter in a Vienna hotel, one of a small group of former concentration camp guards and ardent Nazi loyalists who cling to their shamed ideology and “file away” potentially damning witnesses to their war crimes. If he looks like a man who is quietly scornful of his life, he is. His disdain for a job that involves entertaining spoiled, rich women is palpable and does little to hide his survivor’s guilt. It is almost as though he lives out of obligation, like he knows that he got away and hates the world for making it so easy.

We meet our main characters twelve years after the end of that war and we see how quickly the facades they’ve built in peace time crumble. Max (Dirk Bogarde), is the eponymous night porter in a Vienna hotel, one of a small group of former concentration camp guards and ardent Nazi loyalists who cling to their shamed ideology and “file away” potentially damning witnesses to their war crimes. If he looks like a man who is quietly scornful of his life, he is. His disdain for a job that involves entertaining spoiled, rich women is palpable and does little to hide his survivor’s guilt. It is almost as though he lives out of obligation, like he knows that he got away and hates the world for making it so easy.

These emotions get further complicated with the arrival of Lucia (Charlotte Rampling) to his hotel. She is now an elegant maestro’s wife, but the look on her face when she sees Max for the first time is a complicated one. When you watch this film, pay attention to this scene because it is a testament to silent acting. They both look like they ran into brick walls and at first the expressions are inscrutable, but intense. Whatever their history, you think, it is the kind that dooms people.

Through a series of silent, haunting flashbacks, we get the full story: she was his prisoner in a concentration camp, surviving by becoming his plaything and participant in a sado-masochistic relationship.You get the sense that she entered the arrangement willingly, even if refusing to do so surely meant death. Not long after they reunite in Vienna, they re-kindle this “romance”. This obviously creates some conflict between Max and his colleagues, who view Lucia as perhaps the most dangerous witness to their crimes. Max and Lucia eventually resort to re-enacting their disturbing concentration camp scenes in a darkened apartment, where hunger and fear starts a regression into their former, truer selves.

Through a series of silent, haunting flashbacks, we get the full story: she was his prisoner in a concentration camp, surviving by becoming his plaything and participant in a sado-masochistic relationship.You get the sense that she entered the arrangement willingly, even if refusing to do so surely meant death. Not long after they reunite in Vienna, they re-kindle this “romance”. This obviously creates some conflict between Max and his colleagues, who view Lucia as perhaps the most dangerous witness to their crimes. Max and Lucia eventually resort to re-enacting their disturbing concentration camp scenes in a darkened apartment, where hunger and fear starts a regression into their former, truer selves.

It’s easy to understand why, upon its original release, The Night Porter was considered by its most vehement critics as pornographic and exploitative. After all, it combines sex and the Holocaust in a way that is disturbing when you consider the usual images we associate with this period – the stars, the showers, the striped pygamas. What is short-sighted about this criticism is that it ignores the fact that Nazi culture was inherently exploitative and grotesque. I don’t claim to be an expert on the tastes and proclivities of Hitler’s finest, but if there were a subculture that brought perversity to operatic and artistic heights, it’s the Third Reich. We only ever consider the fact that they are monsters because films and stories about them are always told on the side of their victims. What Cavani does, very intelligently I find, is not to portray them as monsters, but to present them as men and women with monstrously distorted morals and a taste for ugly luxury.

The ending is inevitable, the way they usually are when fate and time don’t coincide. I kind of wish the Criterion set had more (or any) extras, though the website links to a pretty competent essay

As I said, it is a difficult film to watch, not because it is pornographic, or even all that graphic, but because we watch the characters become increasingly desperate as they realize they are no longer suited to the world around them. They give in, slowly, to more dominating forces and with each level of surrender, they become smaller, weaker and more themselves.

– Lena Duong

Visit the Criterion Collection website