Directed by Joel Coen and Ethan Coen

Written by Joel and Ethan Coen

2009, USA

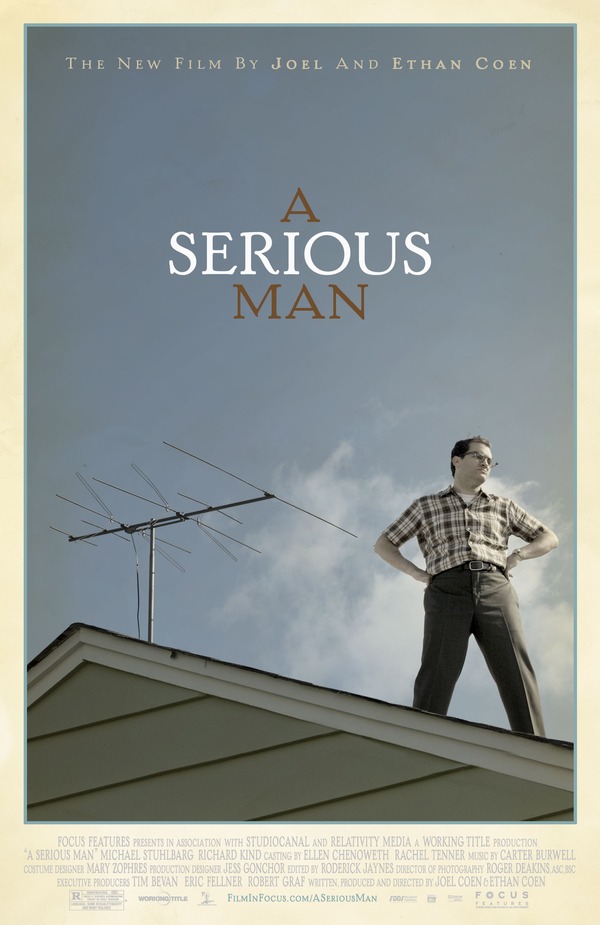

The Coens are getting positively prolific these days, treating their hardcore fans with a movie a year, and with their latest release, A Serious Man they have taken the comedic strand of their work into uncharted waters to deliver possibly their most haunting and certainly their most personal work to date. Introduced in person in their characteristically succinct manner at this year’s LFF, the film, after a mysterious prologue set in a nostalgic Shtetl alights in late 1960’s Minnesota. Jewish professor – and I only stress the Jewish status as it is instrumental to the film’s chutzpah – Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg) is not having a good month. After taking tests for a mystery medical ailment Gopnik is accosted by a disgruntled South Korean student who subsequently attempts to discredit his reputation with anonymous letters to the tenure committee after Gopnik failed him in a critical test. His bickering children ignore him, his redneck neighbour is encroaching on his property with his home expansion designs, and his medically afflicted brother is staying with him to the exasperation of his distant wife, who most distressingly reveals early in the film that she is going to leave him for the affections of scene-stealing widower Sy Albeman (Fred Melamed). Seeking the wisdom of his community leaders, a trio of Rabbis (unconsciously echoing the early, middle, and late stages of life), Gopnik embarks on mid-life odyssey to remain a virtuous man, a serious man, as events conspire to wreck his intrinsically good if somewhat ineffectual nature.

As skillfully as ever, the Coens incrementally pile on the frustrations of Gopnik’s disintegrating existnce whilst drawing forth laughter at his hapless situation – a spoonful of sugar to swallow the bitter pill. This is certainly their most idiosyncratically funny work since Lebowski, but there are darker forces at work here buried beneath the suburban angst. This is no Sam Mendes film – underneath the carapace of the film there is a notion that life is suffering, that destiny is an indifferent, unassailable force. For Gopnik, even a mind-expanding (and potentially physical) sojourn with a sexy neighbour is interrupted by the intrusion of the foibles and weaknesses of our fellow players in the charade of life. As with the ominous coin tosses of No Country For Old Men, the film delves into the parameters of cause and effect, the bell curve chart of fortune and adversity. At first glance, A Serious Man could be the Coens’ most systemically structured film, with Schrödinger’s cat allusions nestling next to a fascinating delineation of the Jewish experience. The film is littered with the religious trappings and cultural mores of the Hebrew faith, with Gopnik’s son Danny’s Bar Mitzvah and his allegorical discussions with the second rabbi serving as the film’s two most hilarious sequences.

As skillfully as ever, the Coens incrementally pile on the frustrations of Gopnik’s disintegrating existnce whilst drawing forth laughter at his hapless situation – a spoonful of sugar to swallow the bitter pill. This is certainly their most idiosyncratically funny work since Lebowski, but there are darker forces at work here buried beneath the suburban angst. This is no Sam Mendes film – underneath the carapace of the film there is a notion that life is suffering, that destiny is an indifferent, unassailable force. For Gopnik, even a mind-expanding (and potentially physical) sojourn with a sexy neighbour is interrupted by the intrusion of the foibles and weaknesses of our fellow players in the charade of life. As with the ominous coin tosses of No Country For Old Men, the film delves into the parameters of cause and effect, the bell curve chart of fortune and adversity. At first glance, A Serious Man could be the Coens’ most systemically structured film, with Schrödinger’s cat allusions nestling next to a fascinating delineation of the Jewish experience. The film is littered with the religious trappings and cultural mores of the Hebrew faith, with Gopnik’s son Danny’s Bar Mitzvah and his allegorical discussions with the second rabbi serving as the film’s two most hilarious sequences.

Regular Coen cinematographer Roger Deakins returns after a one-film break, with stalwart Coen composer Carter Burwell also providing another of his habitually lyrical scores. Neither contributor works to overwhelm the film’s dialogue-driven approach. If it’s possible to chart two alternate strands to the Coens’ career, the crime films (moving from the lo-fi noir of Blood Simple to the homage of Miller’s Crossing, from the bleakly humanist Fargo to their masterpiece, No Country For Old Men) and the comedies (from the broad Raising Arizona to the cultish Lebowski, from curio The Hudsucker Proxy to reverential O Brother, Where Art Thou?) then both strands have been bivouacking at the same nucleus – perhaps the absurdity of life? – with the final scene of A Serious Man mirroring the seemingly abrupt finale that graced No Country For Old Men. A Serious Man is a densely conceived, thoughtful and rewarding film that stands amongst the most significant achievements in the Coens’ extensive filmography.

Regular Coen cinematographer Roger Deakins returns after a one-film break, with stalwart Coen composer Carter Burwell also providing another of his habitually lyrical scores. Neither contributor works to overwhelm the film’s dialogue-driven approach. If it’s possible to chart two alternate strands to the Coens’ career, the crime films (moving from the lo-fi noir of Blood Simple to the homage of Miller’s Crossing, from the bleakly humanist Fargo to their masterpiece, No Country For Old Men) and the comedies (from the broad Raising Arizona to the cultish Lebowski, from curio The Hudsucker Proxy to reverential O Brother, Where Art Thou?) then both strands have been bivouacking at the same nucleus – perhaps the absurdity of life? – with the final scene of A Serious Man mirroring the seemingly abrupt finale that graced No Country For Old Men. A Serious Man is a densely conceived, thoughtful and rewarding film that stands amongst the most significant achievements in the Coens’ extensive filmography.

John McEntee