In October of 2010, Sound on Sight asked me to do my first commemorative piece on the passing of filmmaker Arthur Penn. I suspect I was asked because I was the only one writing for the site old enough to have seen Penn’s films in theaters. Whatever the reason, it was an unexpectedly rewarding if expectedly bittersweet experience which led to a series of equally rewarding but bittersweet experiences writing on the passing of other filmdom notables.

I say rewarding because it gave me a nostalgic-flavored chance to revisit certain work and the people behind it; a revisiting which often brought back the nearly-forgotten youthful excitement that went with an eye-opening, a discovery, the thrill of the new. Writing them has also been bittersweet because each of these pieces is a formal acknowledgment that something precious is gone. A talent may be perhaps preserved forever on celluloid, but the filmography now had a terminus; no additions, no more new chapters.

Some of the losses get by me. As I was thumbing through the most recent issue of Entertainment Weekly, a year-end “Best & Worst of 2011” edition, I was surprised at how many familiar names showed up in the issue’s “Late Greats” section having passed without my knowing it. With your permission, I’d like to pay a quick homage to some of them; for all the entertaining hours they gave me in front of both the big and small screen, it would seem ungrateful on my part not to acknowledge their departure.

I grew up watching Harry Morgan (b. 1915). His was one of those Familiar Faces which seemed a permanent part – a Rushmore – of the entertainment landscape. When I was a kid, I watched him steal scenes as the next door neighbor in syndicated re-runs of 1950s sitcom December Bride, and then there he was, back again, in the 1960s revival of the granddaddy of all police procedurals, Dragnet, playing Jack Webb’s head-nodding partner. Seemingly eternal, he came back – yet again – in the 1970s as the grandfatherly commanding officer on the TV adaptation of M*A*S*H. And there were a hundred other guest appearances, other series, and God knows how many movies. That flat Midwestern nasal twang of his was pitch-perfect for the often caustic, wry pitch which was his trademark. He was a hoot the minute he opened his mouth in movies like The Flim-Flam Man (1967), Support Your Local Sheriff (1967), and what seems like a million others. Because he was so closely associated with comedy, few knew how much dramatic muscle he could muster, and if you really want to see Morgan’s range, watch him as Henry Fonda’s brooding sidekick in The Ox-Bow Incident (1943). “I didn’t really start out to be an actor,” Morgan once said, “I just sort of fell into it. I’ve had a good career, a lot of laughs. I don’t know if that’s enough, but it beats coal mining.” Amen and thanks for a million laughs and a few lumps in the throat, Harry.

G.D. Spradlin (b. 1920) was another Familiar Face we lost in 2011. Most probably remember him as the slimy, corrupt senator in The Godfather: Part II. With his tall, lean, erect frame, Spradlin was often cast as stern authority figures: the coach in North Dallas Forty (1979), the patrician commanding officer of a military school in The Lords of Discipline (1983), and the like. But Francis Ford Coppola saw something in Spradlin most directors never asked for, and gave him the mold-breaking part of a compassionate, troubled military man in Apocalypse Now (1979). You want to see a pro at work? Watch the look in Spradlin’s eyes, hear the softening in his voice as he tells assassin Martin Sheen how his one-time friend (Marlon Brando) has given in to the insanity of the Vietnam War and gone bloodily insane himself.

Dana Wynter (b. 1931) holds a special place in the hearts of sci fi fans of which I consider myself a member of the club. She co-starred with Kevin McCarthy in the original The Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). I can never forget that close up director Don Siegel gives her near the end of the film when she’s kissed by McCarthy who realizes – looking into her flat, cold eyes – that he’s lost his beloved to the invading pods.

Dana Wynter (b. 1931) holds a special place in the hearts of sci fi fans of which I consider myself a member of the club. She co-starred with Kevin McCarthy in the original The Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). I can never forget that close up director Don Siegel gives her near the end of the film when she’s kissed by McCarthy who realizes – looking into her flat, cold eyes – that he’s lost his beloved to the invading pods.

When it comes to Star Trek, I’m a purist; it’s the original 1960s series for me and the rest can be beamed elsewhere. As such, I couldn’t help but feel a pang at the passing of William Campbell (b. 1923), another one of those, “Oh, that guy!” supporting players. Campbell never graduated past the B-list, and was usually cast as some kind of silky slimeball. But, like most character actors, he had more range than he was usually given credit for. I remember him as the brash-talking Confederate trooper father-son bonding with crusty William Demarest in Escape from Fort Bravo (1953), and his disturbing scene in the WW II actioner Breakthrough (1950) where he’s unable to pull himself clear of a burning tank because “I got no legs!” But the Trekkie in me remembers him best for his role in the episode, “The Squire of Gothos,” one of the original series’ best. Cambell eats up the part of the foppish alien Trelane with a spoon, the torments he inflicts on Captain Kirk & Co. turning out to be the pulling-the-wings-off-flies sociopathology of a child masquerading as an adult.

Brit Pete Postlethwaite (b. 1946) already had an extensive resume, particularly in UK TV, when I first noticed him – as most American audiences did – as the mysterious Kobayashi, minion of the feared master criminal, Keyser Sose, in The Usual Suspects (1995). But I didn’t appreciate the range and depth of the guy until I later caught on cable his earlier performance in the true-life drama, In the Name of the Father (1993). Kobayashi is an austere, still pillar in an immaculately tailored suit, an agent of unbounded malevolence, the high priest of bad guy’s boogeyman Sose. Giuseppe Conlon from Father, on the other hand, is a hunched, frail and fearful figure, whose one, great strength is his love for his bedeviled son (Daniel Day-Lewis). In the British tradition, he was a pro who brought dignity and class to whatever set he stepped on, from sci-fi like Inception (2010), to a hardboiled contemporary noir like The Town (2010).

Composer John Barry (b. 1933) may have had as much to do with turning James Bond into an international, inter-generational brand as anybody involved with the franchise. Barry was the composer on all of the early Bonds, and his brassy, kinetic scores were a signature of the series. He may have been most closely identified with the Bonds, but Barry had other colors, too: epic grandeur in Zulu (1964) and Born Free (1966), faded romance in Robin and Marian (1976), neo-noir in Body Heat (1981). My personal favorite: the melancholy, harmonica-carried theme from Midnight Cowboy (1969) which so painfully captured the isolation and disillusionment of souls lost amid the neon-lit canyons of a (then) decaying New York City.

I had an incredible crush on Susannah York (b. 1939) in the 1960s. She was a perfect Carnaby Street icon of the time with her lithe, short-haired, mini-skirted casual sexiness. It didn’t hurt that she was also a hell of an actress, something she would prove time and again in films like Tom Jones (1963), A Man for All Seasons (1966), and, in most harrowing fashion, the Depression-era drama, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969). Nobody got as much mileage out of York’s wide blue eyes as director Sidney Pollock, shooting them through a shower’s spray as the fragile psyche of her wannabe actress Alice shatters from the exhaustion and heartbreak of a desperate dance marathon.

But there was an earlier heartthrob: Anne Francis (b. 1930). If York was late 60s mod, Francis was good ol’ fashioned Hollywood: blonde, curvy, brassy (in her best parts), and with the sexiest facial mole this side of Marilyn Monroe. In retrospect, she may have been too pretty. It was hard – particularly in that era – to get producers and casting people to see past her looks to the strong actress she was. “Most young blondes in those days [’50s] were not taken too seriously,” she once explained. “I had wanted to work on a project [directing] all my own from beginning to end for many years. I had managers who said, ‘Look, you’re an actress. You’re not supposed to do that other business.’” She could play girl-next-door, like the goody-two-shoes wife of inner city teacher Glenn Ford in Blackboard Jungle (1955); the intimidated bad guy’s girl (Bad Day at Black Rock [1955]); and sci fi/fantasy buffs probably remember her from the classic Twilight Zone episode, “After Hours,” playing a woman trapped in a closed department store, haunted by mannequins come to life, only to realize that she, too, is a mannequin who has been on leave in the human world. But she was at her best – and never more alluring – then when she played strong: the free-spirited Altaira in the sci fi classic Forbidden Planet (1956), or – my favorite – as the lead in the mid-60s TV series, Honey West, playing a tough, independent, karate-chopping, guys-can-just-kiss-my-perfect-ass private eye before most people had heard of Women’s Lib.

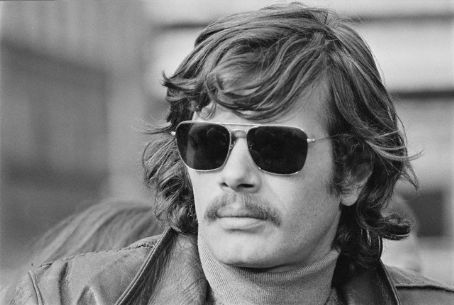

There was a time it looked like whenever a producer needed someone to play the wide-eyed naïf, Michael Sarrazin (b. 1940) seemed to get first call. There was something about those big, blue eyes, the babyish cast of his full-lipped face, his soft voice that spoke of vulnerability and innocence. But Sarrazin was a good enough actor to keep himself from becoming an empty type. As similar as many of his characters were, he made each distinct, alive: Army deserter Curley, frantically fighting off the cynicism being preached by George C. Scott’s con artist in The Flim-Flam Man; the aimless Robert caught up in the misery of a relentless dance marathon in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?; the angry prodigal who returns to his lumberjack family in Sometimes a Great Notion (1970).

One of the funniest men who ever hit the screen was the great Kenneth Mars (b. 1935). He was a master of absurd, ridiculous accents, and at his best when a director stood back and let Mars loose on his ruthless pursuit of a laugh. Few directors knew how to do that. One was the equally ruthless laugh-chaser Mel Brooks who unleashed Mars in The Producers (1968) as Franz Liebkind, an atrocious playwright who pens a virtual “love-letter to Hitler” with his appalling play, Springtime for Hitler; and then again in his spot-on parody, Young Frankenstein (1974), playing a Transylvanian constable whose accent is so thick even the locals can’t understand him!

Of all The Little Rascals, Jackie Cooper (b. 1922) was my favorite next to Spanky. I grew up watching Rascals re-runs on local TV, blissfully unaware that, by that time, the Rascals were all middle-aged. Cooper was the rare child actor who managed to maintain a career – not only as an actor, but as a producer and director — throughout his life. I thought he was a stitch as a cheap, loud Perry White in the first Superman movie (1978), rattling off zingers in screwball comedy style: “Lois, Clark Kent may seem like just a mild-mannered reporter, but listen: not only does he know how to treat his editor-in-chief with the proper respect, not only does he have a snappy, punchy prose style, but he is, in my forty years in this business, the fastest typist I’ve ever seen!” But my strongest memory of him will always be as little Jackie, fumbling through a crush on his school teacher (“Gee, Miss Crabtree…”), ridiculously competing for her attention against fellow Rascal Chubby.

Aussie actress Diane Cilento (b. 1933) had an impressive filmography including roles in such high-profile flicks as Tom Jones, The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965), and cult horror fave, The Wicker Man (1973), but my favorite was as the tough-hided dispossessed housekeeper in the equally tough-hided Western, Hombre (1967). She’s the movie conscience, its referee between what we’d like to do, and what we should do. It’s a rich, full-bodied performance, her Jessie a mix of the melancholic weight of her emotional scars, and her stubborn if battered sense of decency. In a genre which often shorts its women folk, Cilento in Hombre stands far above the crowd.

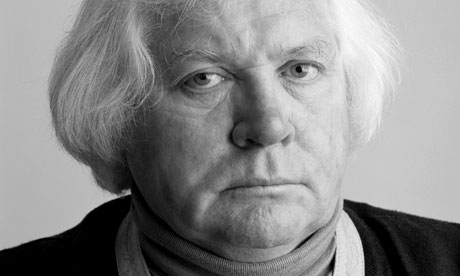

In my younger days, I wasn’t always sure what director Ken Russell (b. 1927) was trying to do. Looking back, I’m not sure Russell always knew what he was trying to do…other than see how far he could go. Russell once said, “I don’t believe there is any virtue in understatement,” and he filmed accordingly. I was introduced to his work in my college days when I saw his screen adaptation of The Who’s rock opera, Tommy (1975). After over 30 years of numbingly over-the-top music videos, it’s hard to appreciate how novel Russell’s visually flamboyant rendering of the rock milestone was at the time. Intrigued by the eye behind Tommy, I began backtracking its director, was struck by the seething eroticism of Women in Love (1969), appropriately disturbed by the fever dream visualization of The Devils (1971). I didn’t always like Russell’s work; there were times I thought him so obsessed with pushing limits that he forgot to tell his story as in Crimes of Passion (1984) and Valentino (1977). But I was always impressed with his audacity, his willingness to see how far off-center he could pull the commercial mainstream…and then try to tug it a little further.

And now they’re all gone. It’s a hell of a movie they’d make: a cast comprised of Jackie Cooper, Diane Cilento, Anne Francis, Michael Sarrazin, Kenneth Mars, Dana Wynter, Harry Morgan, Susannah York, G.D. Spradlin, William Campbell, and Pete Postlethwaite, scored by John Barry, and directed by Ken Russell. It’s a shame that such grand cinema is reserved only for the next world. We here will have to make do with something less.

Bill Mesce