Midnighter is a title that knows what it is and what it’s aiming for. It is a comic about a gay superhero designed for a gay and bi male readership, but with plenty to offer every other reader too. The artwork is inventive and gorgeous, even as it depicts gruesome violence. It knows how to use a metaphor in clear, nuanced ways. It balances grit, hard choices, and vigilante glee. Although I’m not in the primary demographic for this title, I still found myself engaged enough by the end of the volume to want to seek out more of Steve Orlando’s Midnighter issues and disappointed to read that the title was likely canceled with DC’s Rebirth plans. Midnighter fills a clear void in LGBTQ+ hero-oriented comics, and I’ll be sad to see DC scrap it. I hope they reconsider.

Midnighter has been a gay superhero for 20 years and icon for the LGBTQ+ community for as long. He was introduced with his crime-fighting partner Apollo, a kind of analog to Batman and Superman, but gay. Not that that was clear from the beginning. Midnighter has often been a victim of his times depicted as a mirror of what seems acceptable to a cisgendered comics reading audience, and because of that, M’s sexuality has often been mishandled. From being cagey about the orientation in the first place, to having villains throw homophobic taunts, to allowing chaste kisses within life-partnered monogamy, Midnighter has been at the mercy of the day’s acceptability.

Except Midnighter isn’t so much about what others find acceptable. He’s a true vigilante, willing to embrace the darkest parts of night. Is he also a bad guy? That’s the question of identity explored through the volume. Midnighter has a computer in his brain that calculates all possible outcomes in a split second. His body has been enhanced for fighting. He was built to be a weapon. The choices he makes are merely pointing that weapon in the right direction. He repeats he’s a vigilante rather than a hero. He’s got no qualms killing criminals. Just how reckless with life he might be gets detailed in the volume’s opening fight where a little girl appears to be possessed, and for a long, tense moment, the reader wonders if he will kill her or save her. He’s no boy scout. Heck, he’s no Batman, who despite his violence, at least attempts to lock up his antagonists, not kill them. He does sport Batman underwear though–he’s got a pretty great sense of humor.

With Steve Orlando at the reins of Midnighter, the many wrongs done in handling a gay superhero are being righted, and Midnighter is figuring out who he really is. Orlando puts Midnighter’s sexuality front and center as M navigates dating for the first time. He and Apollo have had a falling out after Apollo learned that M’s alter ego was invented. Midnighter doesn’t really know who he was before being weaponized by the God Garden, so he invented a past to try to be more normal, but the guise wasn’t working as intended, and M no longer seeks the “normal” life as desirable. So now on his own, Midnighter has put himself on a dating site, calling himself simply M, and being entirely upfront about being the vigilante Midnighter. It’s an interesting way of addressing concerns of coming out. One of Midnighter’s dates asks him if he’s concerned that he’ll be targeted by not having a hidden identity, read: for not passing as cis. M is entirely confident in his ability to see what’s coming and deal with it–after all, he’s got that brain computer and enhanced body. He has no fears of being assaulted and doesn’t care if he’s hated. He projects the kind of fantasy confidence we all wish we had when faced with revealing a part of ourselves not embraced by our community.

His self-confidence is initially a source of great fun. He’s brazen in battle, throwing casual wisecracks at his assailants. But as the issues go on, it becomes a source of reader fatigue. Midnighter feels a bit over-powered, seems unbeatable. And while we like our heroes to be able to kick ass, we also want to feel the tension of their peril. Midnighter doesn’t ever seem like he’s in real danger. Not until the Big Bad uses his confidence against him, then the complacent position of the reader shows itself to be intentional. We are all the more surprised when he can no longer use his computer to gain victory.

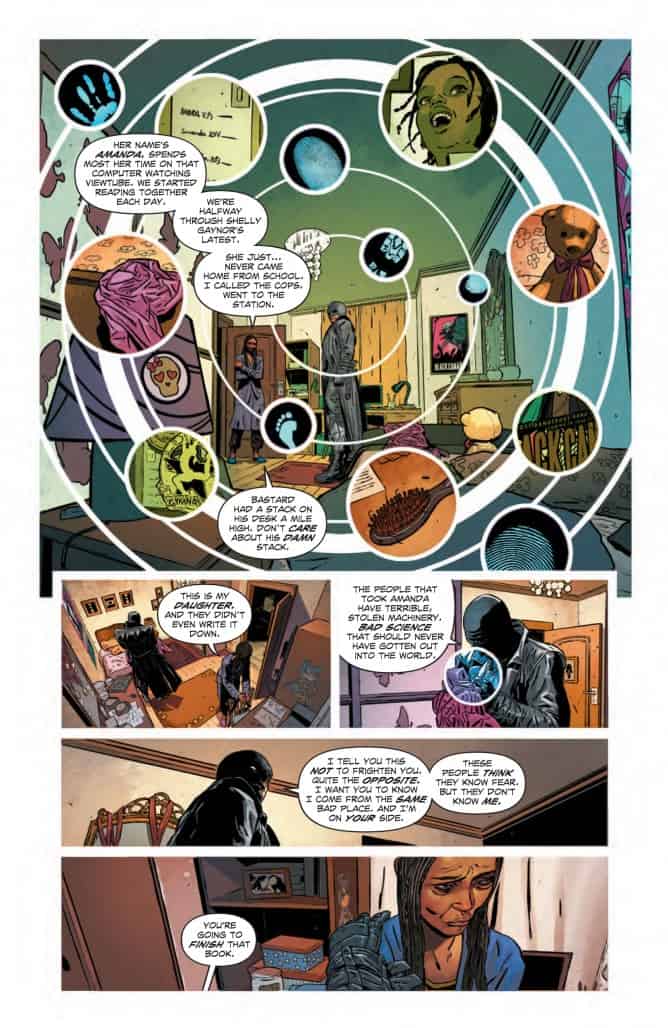

Artistically, the illustration of the computer’s predictions in battle is the most interesting and unique. Depicted as a smattering of snapshot-like insert boxes, the effect is to give a sense of what the computer notices and processes without attempting to run through the whole scenario. It can be a little disorienting at first, since it’s not meant to be linearly followed. Our puny brains cannot comprehend what Midnighter knows. Additionally, the color use is gorgeous, often using a red, white, and blue palate in ironic ways–Midnighter’s no Captain America. Page layout is always inventive yet still clearly progressing plot.

Maintaining DC’s PG13 requirements, Orlando skirts the very edges in his depictions of violence, language, and sexuality. This is a comic meant for older teens and adults. Midnighter is shown dating two different men, both of whom he goes to bed with. The first ends up being only a single date, and afterward the man becomes a friend. The second, with Matt, becomes a long-term relationship, shown with both sensual and emotional engagement. There is kissing that is clearly going to lead to sex, morning after scenes, and sexual flirting. However, that relationship becomes particularly complicated as both Matt and his father become targets for M’s enemies. And even that becomes merely a smoke-screen.

Gone is the homophobia. The only one making gay jokes in this volume is Midnighter himself, who owns his sexuality so confidently that he playfully flirts with Dick Grayson (making the homoerotic subtext between Batman and Robin delightfully explicit) as they team up to defeat a Moscow crime lord bogeyman. Grayson, of course, neither encourages nor repels M’s behavior. He too is comfortable enough to see it as some friendly teasing, nothing more.

My one complaint with Midnighter is that there are only two women in the whole volume. One makes a brief appearance of only a few pages. The other becomes a casual confidante of Midnighter, giving him someone to talk to outside of his social circle. It might be a small complaint considering the strides Orlando gives Midnighter toward being an interesting, complex, but also realistic depiction of a queer superhero. For now, I’ll let it be and hope that future issues bring more gender balance.