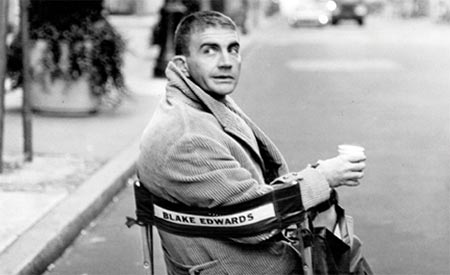

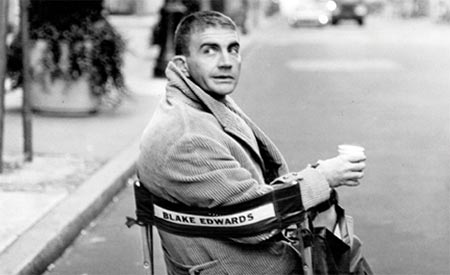

When the news of Blake Edwards’ passing at age 88 broke earlier this month, it stood to reason his obituaries would mandatorily lead off identifying him as the writer/director behind the “Pink Panther” movies and as a “master of sophisticated slapstick comedy.” After all, the “Panther” films may not have been his best work, but, in a career marked by as many flops as hits, they were his most recognized and consistently popular efforts with six films spanning 20 years (excluding 1993’s execrable post-Peter Sellers Son of the Pink Panther).

In the longer obits, it was nice to see his more sophisticated work also remembered like romantic comedy Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), another iconic rom-com for another decade in 10 (1979), his 2/3 brilliant and 100% brutal skewering of Hollywood in S.O.B. (1981), and an early turn at drama with Days of Wine and Roses (1962), still one of the most disturbing portraits of alcoholism in a studio film.

What wasn’t acknowledged – and, so long after the fact, might not even be remembered – is Blake Edwards’ role in bringing the element of cool to the big and little screen.

By the late 1950s, Edwards knew the stodgy, blocky 50s were giving way to a jet age/jet setting vision of something sleeker, smoother, tougher: shoebox Chevys ceding the road to low-slung, bullet-shaped T-birds, poodle skirts surrendering to obscenely snug pencil skirts punctuated with sky-high stiletto heels, broad lapels and fat ties retreating in front of a narrower, more tapered look fitting like a second skin on suave yet diamond-hard Edwards heroes like Peter Gunn, Richard Diamond, Mr. Lucky.

Edwards had tapped into the chrome-sheathed vein of cool even before Sinatra & his Rat Pack turned Vegas into a private playground, before James Bond and Derek Flint did the same for much of the rest of the world, before Newman, before King of Cool McQueen. On TV, Edwards’ footsteps would be followed by the globe-trotting antics (with studio back lots standing in for the globe) of the agents of U.N.C.L.E and I Spy, of The Saint and the light-fingered Alexander Mundy of It Takes a Thief, of the millionaire cop of Burke’s Law …but Edwards had already been there; he’d been the pathfinder.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s Holly Golightly (Audrey Hepburn) was New York cool, an aspiring socialite in Givenchy dresses  who played outside social conventions to rub elbows with mobsters and princes; Mr. Cory (1957) was slum cool as Tony Curtis’ wannabe gambler romanced his way up the social ladder at a Wisconsin resort; and even amongst the hilarity of the original The Pink Panther (1963), David Niven’s jewel thief was the epitome of early 60s jet setting, skiing-in-Gstaad-summers-on-the-Riviera cool.

who played outside social conventions to rub elbows with mobsters and princes; Mr. Cory (1957) was slum cool as Tony Curtis’ wannabe gambler romanced his way up the social ladder at a Wisconsin resort; and even amongst the hilarity of the original The Pink Panther (1963), David Niven’s jewel thief was the epitome of early 60s jet setting, skiing-in-Gstaad-summers-on-the-Riviera cool.

Edwards’ cool wasn’t just about fulfilling male persistently-adolescent fantasies – although that was undoubtedly part of its appeal. It was a recognition that that 1950s air of innocence was falling away; an acknowledgment that the world was a bigger, more textured, more complicated, more violent and certainly sexier place than movies and TV had previously acknowledged. To this day, the noirish jazz bounce of Henry Mancini’s “Peter Gunn Theme” still brings back the vibrancy of something new; the death of the lush, oozy orchestrals of Old Hollywood and the soft-edged sensibility that went with it, and the onset of something more dynamic, more carnal, more deadly.

Consider Edwards’ most popular TV venture, Peter Gunn (1956-61). The popular image of private eyes before Gunn was one of work-a-day gumshoes like Bogart’s Sam Spade in The Matlese Falcon (1941), or rumpled two-suits-in-the-closet types like Dick Powell’s Philip Marlowe in Murder, My Sweet (1944). They were nondescript men of modest means working out of nondescript offices scuffling from one hopefully paying job to the next. Kiss Me Deadly’s (1955) strutting Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) was the exception, but managed it only by being an absolute and totally amoral heel.

But Craig Stevens’ Peter Gunn drove a cool car, lived in a cool apartment, wore cool clothes, dated cool-looking women and, instead of working out of some grubby office, picked up his calls at a cool jazz club. He flashed neatly-creased five-dollar bills at his informants, knew how to mix a cocktail, seemed as at home with the very very rich as with the very very poor.

But Craig Stevens’ Peter Gunn drove a cool car, lived in a cool apartment, wore cool clothes, dated cool-looking women and, instead of working out of some grubby office, picked up his calls at a cool jazz club. He flashed neatly-creased five-dollar bills at his informants, knew how to mix a cocktail, seemed as at home with the very very rich as with the very very poor.

It wouldn’t be long before Edwards’ brand of cool – in fact, the whole concept of cool – became steamrollered by the tragedies and countercultural tides of the late 1960s. The supposed sophistication of Peter Gunn and Mr. Lucky seemed paradoxically naïve and clueless as assassination piled on assassination, the Vietnam War grew from back page item to consuming the national consciousness, and cool was replaced by a proudly grubby look of long hair, tie-dyed T-shirts, and ragged jeans.

Edwards seemed at a loss as to how to respond to the new cultural milieu, and began turning out a string of clunkers like Darling Lili (1969) and The Tamarind Seed (1974). He didn’t get his commercial feet under him again until he returned to the innocent, timeless fun of the “Panther” movies with The Return of the Pink Panther (1975).

That late 50s/early 60s brand of cool may seem quaint now, innocent in its own way, maybe even flat-out corny from a remove of forty-odd years. But in an era of trashy Housewives from Wherever and the prime time cable cavorting of the spoiled rich, reality shows where teen pregnancy has become the aspiration of trailer park wannabe celebs, where hip-hop and pop stars brag about dragging their street cred into the Hollywood hills rather than graduating past it, there is something to be said for Blake Edwards’ cadre of cool dudes who knew a good wine from a bad, held the door for a lady stepping into their T-bird, and always knew the right fork to use.

– Bill Mesce