Directed by Joe Carnahan

Written by Joe Carnahan

US, 2003

It’s a bitterly cold early morning in a slum neighborhood in Detroit, MI, but that doesn’t stop two men from braving the conditions in sparse clothing. They’re high as kites and running at full pelt anyway, plus they have more pertinent things of their mind. Only a few minutes before they were pumping heroin into their bloodstreams, now one is chasing the other down alleyways, over walls and through parks. The hunted man, already bleeding from the face from the early stages of a scrap, slows down long enough to stab his syringe into a mailman’s throat, knowing that his desperate pursuer is duty-bound to stop and help. Coming across the screaming victim, the hunter quickly makes the harsh decision to continue, judgment perhaps compromised, and with expression emotionally torn, abandons him.

Eventually, he catches up with his mark, who now holds up a child as hostage in a play park. Adrenaline pumping and world around him vivid, the pursuer draws his berretta and wildly opens fire, hitting jungle gyms and fences before one bullet eventually finds the criminal’s forehead, dropping him. Rescuing the young child from the dead man’s grasp, he is devastated to find that a ricochet has caught the girl’s pregnant mother in the thigh, from which she bleeds profusely. The last man standing attempts to stem the flow of claret, using his own Hawaiian shirt as a makeshift tourniquet. It doesn’t take. Overwhelmed, he cranes his head up and screams, like a wounded animal, for help. This is Detective Nick Tellis (Jason Patric), undercover cop, and these are the extraordinary opening moments of Narc, a sensational introduction to one of the noughties’ most memorable cop drama/thrillers.

Rarely does a prologue sequence set the tone for proceedings so succinctly, the key word being tone. Joe Carnahan’s first major motion picture, following his low rent but visually impressive debut flick Blood, Guts, Bullets & Octane, Narc went through trials of strength and endurance mirroring the endeavors of its characters in getting made. With twenty one producers, including Tom Cruise, scratching up a $6million budget that stretched to a limited and fee waiving cast and wholesale use of Toronto as a stand-in for Detroit, Carnahan’s baby was a talent propelled ordeal. This seeps into the grungy, audaciously mounted storyline, a consistent feeling of raw passion, raw emotion and ultimately raw storytelling. The opening sequence, a fierce right hook to the audience, is indicative of a Writer/Director whose sweat pumps for his art. The result is the viewer’s complete attention, along with his nervous anticipation and sharing in a sense of post traumatic stress.

This moment defines a story which never lets up its dark feelings of complex morality and explores the shadier, corrupting side of ‘heroic’ police work. Patric’s Tellis has been working the insides of a local drug ring for over a year, and his arduous infiltration that has flirted with addiction and loss of soul has been blown, resulting in the confrontation with and eventual execution of the his dealer. The pregnant bystander ultimately miscarries, and Tellis is suspended for eighteen months, giving him the chance to spend time with his wife and his own child. When the DPD come back into his life, a review board turning out to be an impromptu job offer to help investigate the cold case murder of a fellow narc, he is initially disgusted by the lack of loyalty shown to him.

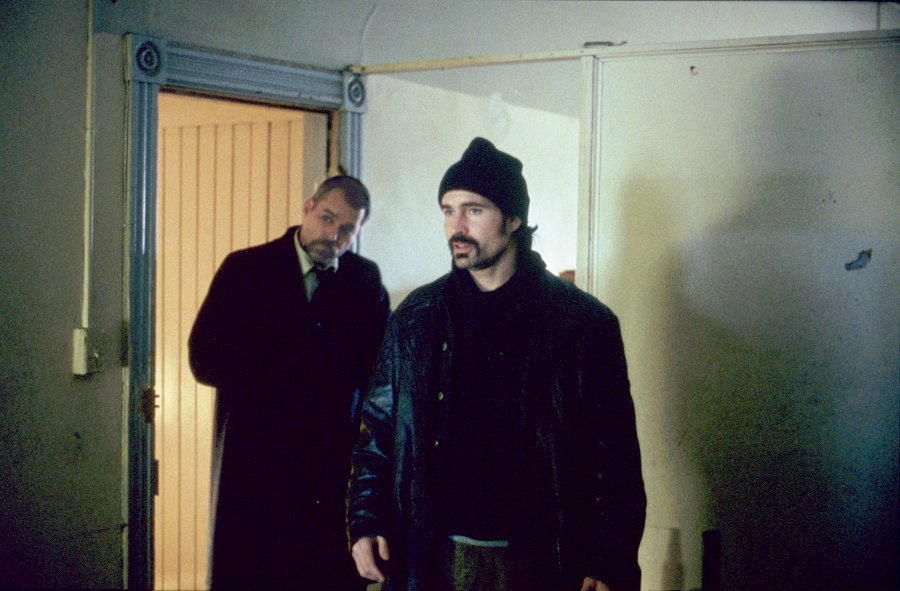

He caves at the prospect of being unemployed and unemployable however, and barters a deal that will eventually land his reinstatement to a desk job. All he has to do is figure out the apparently unsolvable killing of Michael Calvess, gunned down in an underpass tunnel deep in the ghettos. Enter the dead man’s near psychotic partner, who has been flying the lone flag for an investigation apparently not in the department’s best interests; Detective-Lieutenant Henry Oak (Ray Liotta). Forming an unlikely partnership, the pair track down leads and informants in search of a wholly unsatisfying truth.

While the premise is far from original (the film’s detractors cite its unoriginality in the significant cons section of reviews), the element that separates Narc from any of the other dozens of similarly set up cop dramas is in its bare knuckle presentation and honest integrity. There is no sense of conceit within the pages of the story, one which depicts gangland drug rings as a miserable cesspool of depravity, poverty and desperation and the cops as genuine human beings constantly struggling with their own sense of ethics, honesty and priorities. Scenes stand out due to the intelligent and naturalistic dialogue between the dual protagonists, the murky and ugly framing of the slums they search and stake out, and a gritty feel which amplifies any moment of excitement or brutality to vicious levels of visceral. While creating a quasi-realistic world for these flawed characters to inhabit, this treatment also takes in a more symbolic aspect to the film, one that is powered by its powerful questions as much as the noir-esque route of their case.

Much like in Carnahan’s latter year big hitter The Grey, there is a palpable subtext writhing below the surface of the plot. The film’s trailer opening with a quote by Voltaire isn’t just a spurious attempt at levity, it genuinely meshes with the mood of the piece. Despite losing so much to his time working undercover, Tellis still seems to have a firm grip on his principles on the subject of truth and justice, judging each man by his actions done. The red oni to Tellis’ blue is Oak, a man always a split second from exploding into rage and retributive action. His moral code is, by his own admission, skewed to favor those he cares about and to ignore the rights of the faceless criminal echelons. He lays this down when he first meets Tellis, explaining that the only thing he cares about his finding Calvess’ killer, potentially to the detriment of any rule book he once swore to. This is after we’ve met him, with the veteran cop’s first introduction to the audience his brutal beat down of a handcuffed prisoner by way of billiard balls in a sock. As with Tellis’ first scene, we learn all we need to know about how these men handle themselves at the earliest possible moment. As well as making for quality character establishment, it also sets up perfectly to a finale that even amongst twists and turn still manages to achieve something unexpected and emotionally powerful.

It’s not just Carnahan’s cinematic smarts that ensures the final revelation is a heart stopper, however, nor the grim mood of truth set against a backdrop of loss that renders such philosophizing hollow. The film owes a large debt to its two stars, both of him took severe pay cuts in order to appear. Ostensibly one foot ahead of his colleague in the starring stakes, Jason Patric delivers what is possibly the best performance of his career as the complicated and damaged Tellis. The character could easily have been a single not enabler to the events of the film, but Patric is able to bring a quality of understated consistency that makes him not only a solid protagonist but a believable one. He is haunted by the past, troubled by the present and knows he’s stretching too much in hope of a better future. At home, he fights with a wife who fears his death any day, while at work he is sucked further into the murk by the ruthlessness of his unstable and possibly untrustworthy partner. He begins to sense that while he seeks the truth, Oak is merely seeking a truth that suits him. Like in his undercover days, he plays along and rides the wave, too invested in Calvess to throw in the towel. It doesn’t get any easier for him.

Patric’s superbly judged subtlety provides the perfect platform for Liotta to put on a powerhouse display that amazingly manages to avoid the pratfalls of clichéd pantomime. In fact, the term cliché is appropriate because at least on paper Oak is this incarnate; the grizzled, maverick detective. He’s a widower who has seen too much frontline police work on the frontlines to ever hope to be normal again. We never see his private life because he doesn’t have one. His one and only passion and interest is the Calvess case, and all the weight that comes with it.

That passion stretches from solving a case to avenging his best friend and getting justice to the man’s family, a unit that he has become a close friend to. Anybody jeopardizing his crusade, or even questioning its merits, quickly becomes an enemy to his harsh words and intimidating wrath, Tellis included. Pumped up on a carbohydrate laden diet and donning a fat suit, Liotta’s trademark intensity and aggression is perfectly supplemented by the physicality of a character who resembles a bear both in terms of appearance and personality. Overly protective and brutally uncompromising, the discovery that his campaign is one of retribution rather than redemption is hardly a surprise, but the final admission puts him in a vulnerable light, one he has flirted with occasionally.

A sublimely written conversation between Tellis and Oak during a stakeout, in which Oak talks about his late wife, shows that rather than simply being a monster with a badge, he is a deeply troubled man who has embraced his work too fiercely in the wake of personal loss. The death of Calvess, his close friend, has clearly pushed him too far out to come back. Oak is not just a beautifully written character in plot terms, he’s one of the best portrayed cops in recent memory. His complexity matches that of Tellis, just in much different terms. Liotta, frankly, was robbed by not receiving at least a nod from the Academy for his underpaid work.

It was perhaps a little too grim and raw to be considered. The film that is, one that barely got off the ground and, even in making back double its meager budget, barely made a splash. It’s only in the years since that it has drawn the attention and praise it deserves, and has been recognized as a statement of intent from Carnahan. Though the writer/director has only recently began to build on that promise, with the similarly sublime The Grey, it should be remembered that Narc is on if itself a glowing triumph not only for him but for the ranks of ambitious but struggling filmmakers with nothing but a fantastic screenplay and a heart for the project to offer. Matching its scripting with a blisteringly powerful direction, one that burns itself on to one’s memory from the opening seconds onwards, it proves to be raw and gritty crime story at its finest, one that overcomes the familiarity of its set up with an intelligent and thoughtful soul and searing honest attitude. Brilliantly written, wonderfully directed and flawlessly acted, Narc stands tall in its genre and is truly, sadly, unsung.

Scott Patterson