Written and directed by Jean Renoir

USA, 1945

There is a degree of irony in the fact that The Southerner was the one film for which Jean Renoir received a Best Director Academy Award nomination. After all, this was the man behind such films as Boudu Saved from Drowning (1932), The Crime of Monsieur Lange (1936), Grand Illusion (1937), La Bête Humaine (1938), and his masterpiece among masterpieces, The Rules of the Game (1939). Now of course, those films were not made in America, so that in itself, to a large extent, resulted in his Oscar-less appreciation by this point. And the Oscars have never been infallibly valuable signifiers of film quality anyway. But still, that it would take this 1945 film—not a great movie, but not a bad one either—to get Renoir individual attention in what is seen by many as the pinnacle arena of motion picture recognition is somewhat amusing.

Having fled war-ravaged Europe, Renoir was welcomed to the Hollywood community, even if his subsequent endeavors, from Swamp Water (1941) to The Woman on the Beach (1947), were not always as productive nor as substantial as they could have been. With less oversight and fewer restrictions than he would contend with on these other projects, The Southerner, based on George Sessions Perry’s 1941 novel “Hold Autumn in Your Hand,” proved to be a generally pleasant experience for Renoir, his most satisfying in America.

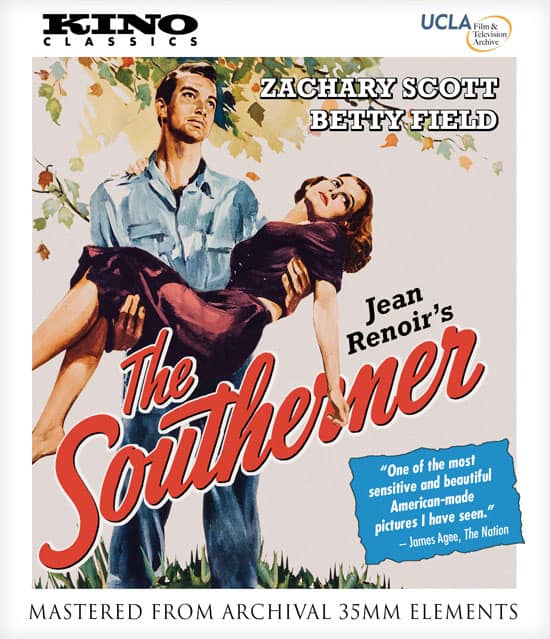

After the film opens with angelic harmonizing over shots of farmers picking cotton, in a reverential rhapsody that accentuates the beauty and the humanity in the toil, the main players are introduced, primarily Sam and Nona Tucker (Zachary Scott and Betty Field), their two young children, and Granny Tucker (Beulah Bondi). While there are people exerting the effort, The Southerner conveys a deference for the livelihood and the crop above all else, even over the specific characters who, in the end, come to represent types more than complex individuals. But as an uncle passes away in this opening sequence, it also becomes clear that the labor can take its toll.

After the film opens with angelic harmonizing over shots of farmers picking cotton, in a reverential rhapsody that accentuates the beauty and the humanity in the toil, the main players are introduced, primarily Sam and Nona Tucker (Zachary Scott and Betty Field), their two young children, and Granny Tucker (Beulah Bondi). While there are people exerting the effort, The Southerner conveys a deference for the livelihood and the crop above all else, even over the specific characters who, in the end, come to represent types more than complex individuals. But as an uncle passes away in this opening sequence, it also becomes clear that the labor can take its toll.

An opulent environment surrounds and visually envelops these characters, setting up what will be a pronounced contrast when Sam and Nona begin to work on their own land and are faced with far less prosperous conditions. Once they secure the property, their ramshackle house is in shambles, the ground is in dire need of attention, and there is a lack of readily accessible drinking water. So while Sam finally gets a piece of land to work, and in this he attains the agricultural autonomy he so longed for, it is a risky venture, even if a nobly ambitious one. Running a year’s time, from fall to fall, The Southerner’s episodic chronicle of hardship has the Tucker family confronted by sickness, storms, cold, hunger, and the cruelty of mankind, chiefly a less than hospitable neighbor who is (understandably) bitter at what the farming life has cost him.

With the family and their possessions piled high in a truck as they set off to start a new life, The Southerner recalls The Grapes of Wrath (1940) with its own interest in the plight of “the people.” It’s not as deliberately universal as John Ford’s film, but there is a similar sense of dignity in the face of adversity and steadfast optimism in the face of potential prosperity. In The Southerner, the scenes of seemingly one complication after another produce the obvious sympathy, but the moments of joy despite these hindrances are even more emotionally gratifying. The simple pleasures of a hot cup of coffee, a fresh possum dinner, or a blanket-turned-winter-coat are the details that make the film notable for its realism and its charming temperament. Though the one major area where Renoir did not get everything he desired on the production was having to settle for RKO properties in California and other nearby sites rather than his initially planned Texas shoot, you have to give credit to the Frenchman for capturing and conveying such distinct cultural flavor (perhaps he did because he was, in fact, a foreigner and could pick up on features otherwise overlooked).

With the family and their possessions piled high in a truck as they set off to start a new life, The Southerner recalls The Grapes of Wrath (1940) with its own interest in the plight of “the people.” It’s not as deliberately universal as John Ford’s film, but there is a similar sense of dignity in the face of adversity and steadfast optimism in the face of potential prosperity. In The Southerner, the scenes of seemingly one complication after another produce the obvious sympathy, but the moments of joy despite these hindrances are even more emotionally gratifying. The simple pleasures of a hot cup of coffee, a fresh possum dinner, or a blanket-turned-winter-coat are the details that make the film notable for its realism and its charming temperament. Though the one major area where Renoir did not get everything he desired on the production was having to settle for RKO properties in California and other nearby sites rather than his initially planned Texas shoot, you have to give credit to the Frenchman for capturing and conveying such distinct cultural flavor (perhaps he did because he was, in fact, a foreigner and could pick up on features otherwise overlooked).

Sam and Nona are a sweet couple, with two admirably resilient children who quite remarkably go with the flow with no complaints. Nona especially is laudable in her unwavering commitment to the life set forth by Sam, which she accepts unquestioningly and, what is more, puts in a respectable amount of work toward, in the field and at home. Yet despite the undeniable earnestness in the characters and their dreamy idealistic perseverance, the performances are not much to speak of (the perpetually complaining Bondi in particular strikes a single note as the cantankerous granny who provides steadily stale comic relief). The film in general gets a little hackneyed with its homespun philosophizing; this is where the acting and the script are at their worst. But as The Southerner moves along, there are times when something poignantly endearing develops, concerning the virtue of the characters, their resolution, and the film’s own veneration for the subject matter.

Sam and Nona are a sweet couple, with two admirably resilient children who quite remarkably go with the flow with no complaints. Nona especially is laudable in her unwavering commitment to the life set forth by Sam, which she accepts unquestioningly and, what is more, puts in a respectable amount of work toward, in the field and at home. Yet despite the undeniable earnestness in the characters and their dreamy idealistic perseverance, the performances are not much to speak of (the perpetually complaining Bondi in particular strikes a single note as the cantankerous granny who provides steadily stale comic relief). The film in general gets a little hackneyed with its homespun philosophizing; this is where the acting and the script are at their worst. But as The Southerner moves along, there are times when something poignantly endearing develops, concerning the virtue of the characters, their resolution, and the film’s own veneration for the subject matter.

Jean Renoir went into The Southerner with lofty intentions, writing years later that he envisioned, “a story in which…every element would brilliantly play its part, in which things and men, animals and Nature (sic), all would come together in an immense act of homage to the divinity.” What also attracted him to the story was, “precisely the fact that there was really no story, nothing but a series of strong impressions,” citing the landscape, the aspirations of the hero, the hunger, and the heat, a series of elements via which the characters would attain a level of spirituality as a result of their day to day existence. I wouldn’t say the film ever truly reaches this high-minded outcome, but it has heart, and it’s always interesting to see what a generally unimpeded great director does with material he cares so much about.