Written by Giuseppe De Santis, Carlo Lizzani, Gianni Puccini

Directed by Giuseppe De Santis

Italy, 1949

The opening credits of Bitter Rice parade an array of Italian film industry luminaries, figures who would help redefine the country’s national cinema, picking up where neorealism left off and setting the stage for the remarkable work that would emerge in the decades to come. Screenwriters Carlo Lizzani and Giuseppe De Santis (who also directed) were two of eight individuals contributing in one way or another to the script, though they were the two who would share an Academy Award nomination for its story. Cinematographer Otello Martelli had nearly 50 films under his belt by the time of Bitter Rice, but in the years that followed he would most memorably man the camera for Federico Fellini’s finest films. And producing the movie was the venerable Dino De Laurentiis, really just at the start of his legendary career. Starring in the picture are Vittorio Gassman, who had his best work still to come, and Silvana Mangano and Raf Vallone, both relative newcomers who, like Gassman, would star in a number of excellent features down the road, collaborating with the likes of Pier Paolo Pasolini, Luchino Visconti, and Vittorio De Sica. All these individuals lent Bitter Rice an exceptional degree of talent, and their varying backgrounds and approaches unified to create a complex film of surprising eroticism, thoughtful realism, vivid melodrama, and wildly fluctuating tone.

Bitter Rice is set largely amidst the open agrarian vista of Vercelli, where every year a congregation of women of all ages, sizes, social origins, and intentions are essentially hauled in to do 40 days’ worth of work, corresponding to the duration of the rice picking season. That the workers are all women is key. As a radio show announcer states at the beginning of the film, only women can do this type of job. It requires small, fast hands, the “same hands that thread a needle and cradle an infant.” Now of course, to today’s ears such a simplistic (some would say sexist) declaration rings with the echo of days thankfully gone by. But in the context of this film, the existence of predominantly female characters is integral to the drama that develops and, it must be said, to the sex-based luridness of the movie. There are men present, but they mostly just take their effortless cut in the profits and lustily take in the sights of the women, pants and skirts hiked high, bent over with full-figured rumps protruding into the air. However accurate it may be, images like this physical position, which is at times blatantly exploited by camera placement, add considerably to the tawdry nature of the film and its occasionally rampant sensuality.

Bitter Rice is set largely amidst the open agrarian vista of Vercelli, where every year a congregation of women of all ages, sizes, social origins, and intentions are essentially hauled in to do 40 days’ worth of work, corresponding to the duration of the rice picking season. That the workers are all women is key. As a radio show announcer states at the beginning of the film, only women can do this type of job. It requires small, fast hands, the “same hands that thread a needle and cradle an infant.” Now of course, to today’s ears such a simplistic (some would say sexist) declaration rings with the echo of days thankfully gone by. But in the context of this film, the existence of predominantly female characters is integral to the drama that develops and, it must be said, to the sex-based luridness of the movie. There are men present, but they mostly just take their effortless cut in the profits and lustily take in the sights of the women, pants and skirts hiked high, bent over with full-figured rumps protruding into the air. However accurate it may be, images like this physical position, which is at times blatantly exploited by camera placement, add considerably to the tawdry nature of the film and its occasionally rampant sensuality.

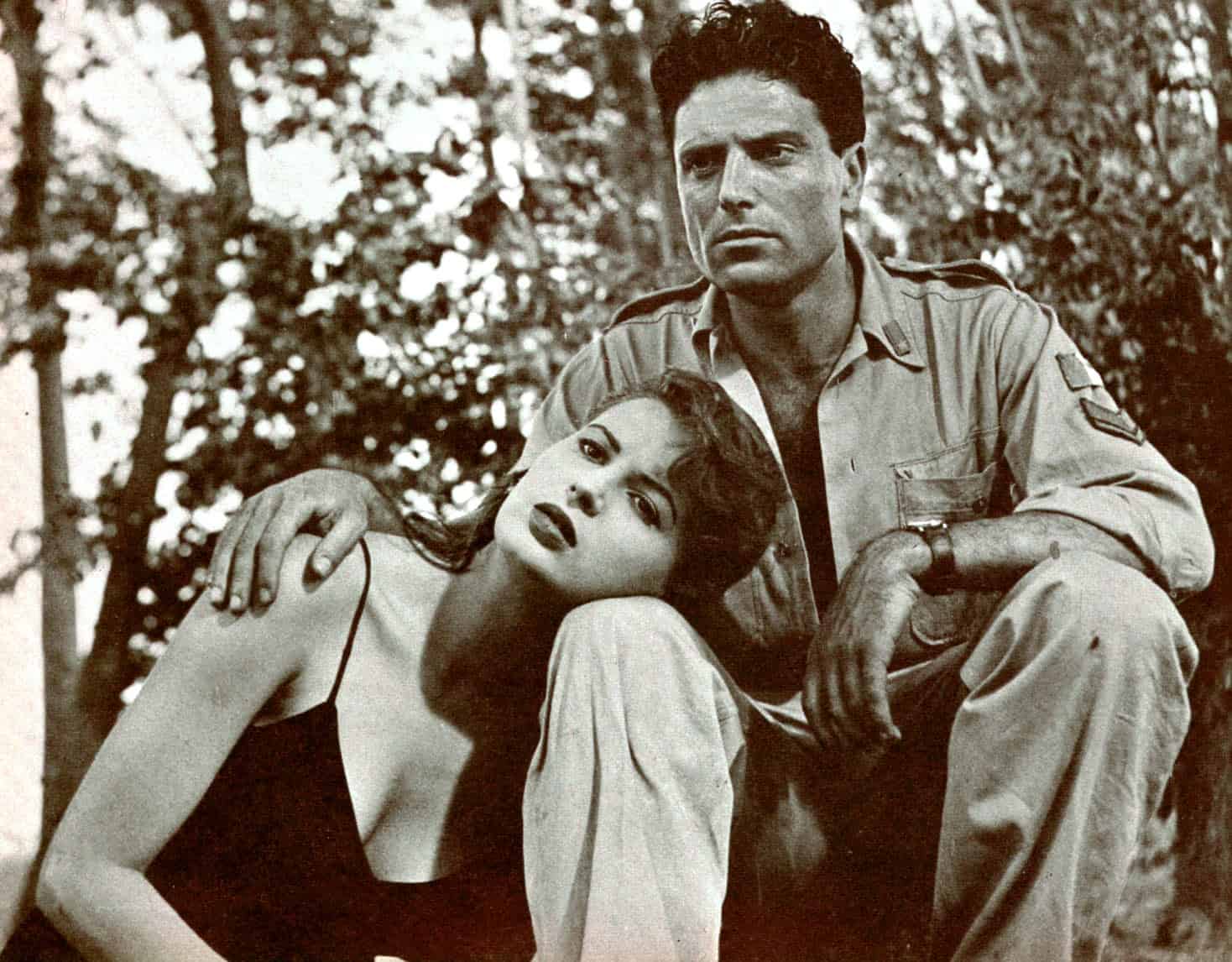

It’s into this world that jewel thief on the run Walter (Gassman) enters with his naively devoted girlfriend Francesca (Hollywood beauty Doris Dowling). They are attempting to evade the authorities and catch a ride out of town. As the two strike an awkwardly artificial pose gazing off into the distance from a train car, the elevated camera glides away and sweeps to a spread near the tracks where Silvana (Mangano) is seductively dancing. She immediately secures the attention of Walter, who to his own detriment hops off the train and heads her way. This is a fantastic introduction to the teenage Mangano’s character, one that underscores her ensuing importance as a major player in the film and one that sets up the love triangle (later quartet) that will be the ruin of more than one life. Police briefly track down the careless Walter, just long enough to draw their guns and just long enough for him to promptly—and tellingly—hide behind Francesca; this is the type of man we’re dealing with here. Nevertheless, he manages to escape and runs off as Francesca, stolen goods in hand, is left to fend for herself, leaping aboard a rice field bound train that also carries Silvana.

With the obvious impression that she knows more than her fair share about illicit activity, Silvana is quickly wise to the theft and witnesses Francesca stashing the pilfered necklace. Suffice it to say, before long the jewelry is soon adorning her own neck, intensifying the already established animosity between the two women. Adding the final ingredient of tension is the generally decent Marco (Vallone), one of several displaced soldiers idling nearby. He takes an amiable interest in the girls, but once Walter reemerges with plans to make a move on the enticing Silvana and steal a shipment of the procured rice in the process, the conniving crook rapidly raises the ire of the jealous sergeant. The romantic and criminal scheming begins. And grows and grows.

With the obvious impression that she knows more than her fair share about illicit activity, Silvana is quickly wise to the theft and witnesses Francesca stashing the pilfered necklace. Suffice it to say, before long the jewelry is soon adorning her own neck, intensifying the already established animosity between the two women. Adding the final ingredient of tension is the generally decent Marco (Vallone), one of several displaced soldiers idling nearby. He takes an amiable interest in the girls, but once Walter reemerges with plans to make a move on the enticing Silvana and steal a shipment of the procured rice in the process, the conniving crook rapidly raises the ire of the jealous sergeant. The romantic and criminal scheming begins. And grows and grows.

As this heated drama plays out in the foreground, Bitter Rice is perhaps at its best when it pulls back to highlight the methodology of the rice picking and the lives of those who undertake this clearly exhausting work. Just as powerfully expressive as the primary characters are in their more intimate moments, so too are the wider shots impressive in their scope of the endeavor. Gone in this 1949 production may be the urban hallmarks of World War II and its ravages, but De Santis and his team retain the neorealist knack for grittiness and legitimacy, with an edifying emphasis on the laborious procedure of the harvest and an effective use of marvelously authentic set pieces to serve as documentary backdrops for the fictional tragedies. Like its immediately post-war predecessors, there is a markedly rich texture to Bitter Rice, one that uncovers in captivating detail the environment, the annual industry, and the people who toil in the fields.

Purely as a result of its date of production, World War II never seems to be far away from a film like this, either as something implied or something voiced outright. But Bitter Rice develops along other thematic and generic strands as well. When Francesca recalls her troubled relationship with Walter, as jazz music plays along in the background, the film suddenly takes on the tenor of a remorseful noir. Yet later, one particularly overblown death scene reaches the level of fever pitched melodrama. And more than once the film’s passionate interests resemble a sensational potboiler, not unlike Luchino Visconti’s Ossessione (1943), on which De Santis worked as a writer. Finally, at the conclusion of the picture, Francesca has a touching change of heart when she refuses to go along with the rice-stealing plot, contending that those Walter now plans to rip off are honest, hardworking people. It’s hardly enough to turn the film around as a full-fledged vehicle for moral messaging, but the point is clear: to steal from those living a leisurely life is far different than to steal from those who know no such luxury.

In his essay on Bitter Rice, which is included with the newly released Criterion Collection disc of the film alongside a documentary about De Santis and an interview with Lizzani, Italian film scholar Pasquale Iannone points out the film was a success when first released, and part of its reception included debate about its sociopolitical content. “For some on the left,” writes Iannone, “the film’s focus on romantic and sexual intrigue obfuscated, even sullied, its social message, a criticism that the director rejected.” Be that as it may, this web of form and content is what makes Bitter Rice such an interesting watch. Whether or not each of its characteristics are given equal and sufficient attention, the sheer brashness of its commitment to mix and mingle seemingly disparate themes, images, and concentrations is a laudable effort in itself.

In his essay on Bitter Rice, which is included with the newly released Criterion Collection disc of the film alongside a documentary about De Santis and an interview with Lizzani, Italian film scholar Pasquale Iannone points out the film was a success when first released, and part of its reception included debate about its sociopolitical content. “For some on the left,” writes Iannone, “the film’s focus on romantic and sexual intrigue obfuscated, even sullied, its social message, a criticism that the director rejected.” Be that as it may, this web of form and content is what makes Bitter Rice such an interesting watch. Whether or not each of its characteristics are given equal and sufficient attention, the sheer brashness of its commitment to mix and mingle seemingly disparate themes, images, and concentrations is a laudable effort in itself.