Written by Fritz Lang, Thea von Harbou

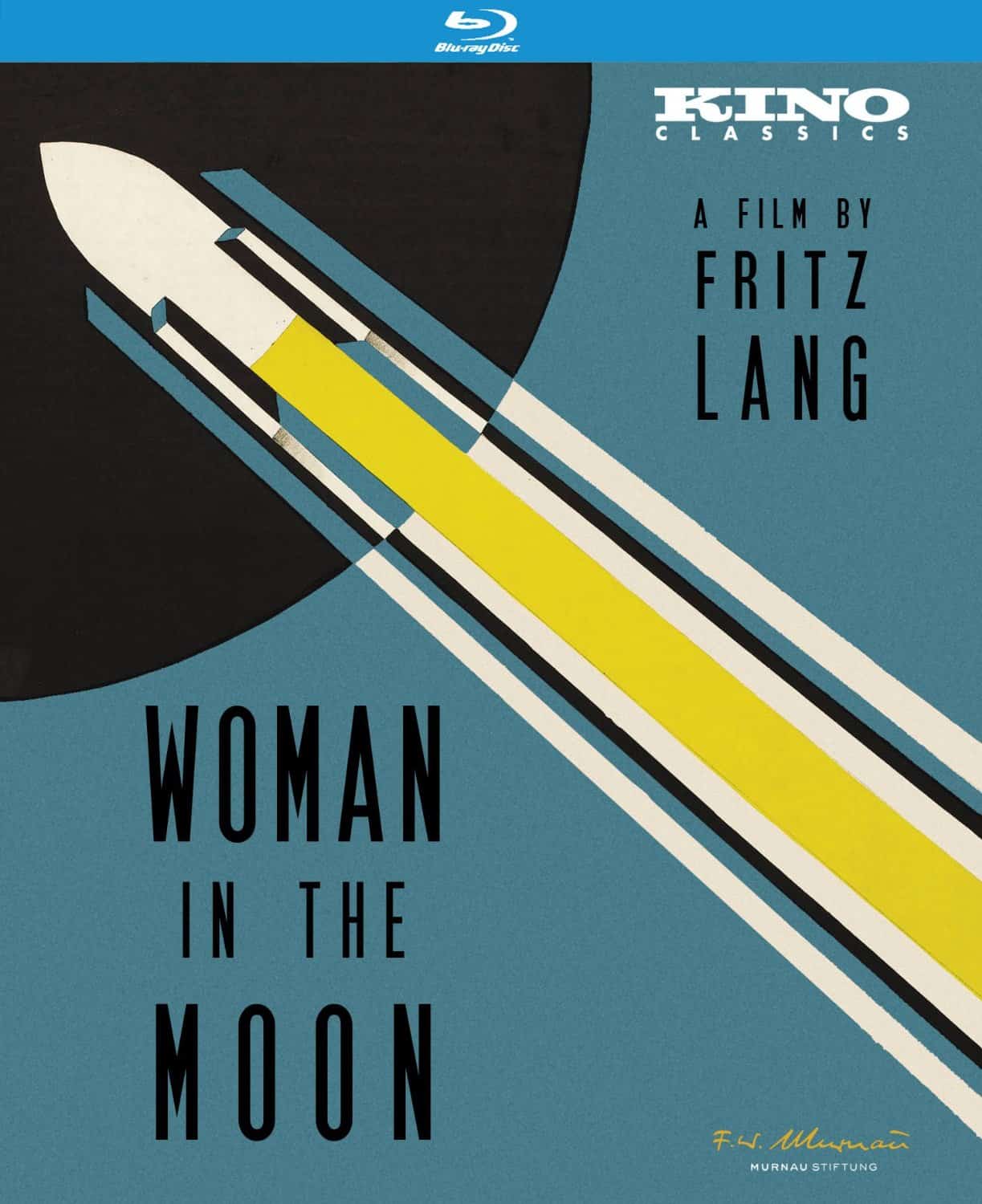

Directed by Fritz Lang

Germany, 1929

At the beginning of Fritz Lang’s Woman in the Moon, a printed proclamation reads: “‘Never’ is inadmissible to the human spirit. At the most, it is ‘not yet.’” A sense of possibility and discovery is at the heart of this 1929 film, setting up the motivational drive of the narrative and emerging as a sweeping theme of the picture, often overshadowing its own plot. With technology surrounding the development of rocket science being a subject of wide speculation and public interest at the time, this science fiction production was released during a moment of innovation and curiosity. As such, Woman in the Moon is refreshingly grounded in science. This is by no means a necessity for a sci-fi feature, but when appropriate facts and technical figures are integrated seamlessly into a film (see Ridley Scott’s The Martian [2015] for a more recent example), the effect can be markedly more engaging. Here, Lang devotes considerable attention to the outlining of schematics and the various processes of space travel. Of course, this being 1929, much of the apparent logic proved to be false. But there is a good deal from the film that ended up being prophetically accurate and literally altered certain notions of interplanetary exploration.

Before the story of Woman in the Moon gets underway, however, several credits are worth noting. For one, the film begins with a collaborative roster of individuals on a single title card, making clear that the production was guided by more than Lang alone. This is a laudable division of recognition on the legendary director’s part, especially given his preeminent place in the German film industry. Among those receiving due attention is Thea von Harbou, Lang’s wife at the time and author of “The Rocket to the Moon,” the 1928 novel that served as the movie’s source. Prof. Hermann Oberth is credited for compiling scientific material and Willy Ley is named technical advisor; both acknowledgements further bolster the film’s standing then and now as one that takes its content seriously. And finally, perhaps most curiously, there are no less than four cinematographers named: Curt Courant, Oskar Fischinger (his only credit ever as cinematographer), Konstantin Tschetwerikoff, and Otto Kanturek.

Before the story of Woman in the Moon gets underway, however, several credits are worth noting. For one, the film begins with a collaborative roster of individuals on a single title card, making clear that the production was guided by more than Lang alone. This is a laudable division of recognition on the legendary director’s part, especially given his preeminent place in the German film industry. Among those receiving due attention is Thea von Harbou, Lang’s wife at the time and author of “The Rocket to the Moon,” the 1928 novel that served as the movie’s source. Prof. Hermann Oberth is credited for compiling scientific material and Willy Ley is named technical advisor; both acknowledgements further bolster the film’s standing then and now as one that takes its content seriously. And finally, perhaps most curiously, there are no less than four cinematographers named: Curt Courant, Oskar Fischinger (his only credit ever as cinematographer), Konstantin Tschetwerikoff, and Otto Kanturek.

As for the cast, Klaus Pohl is Professor Georg Manfeldt, a brilliant scientific mind obsessed with the prospect of space travel and the theory that the moon harbors a wealth of gold. Though he once proposed this concept to the scientific community and was met with boredom and derision, his intense study has never waned. Now disheveled and a little mad, the professor resides in destitute conditions; there is but a single three-legged chair in his shabby apartment and he hasn’t even money for bread. If he has evidently seen better days, he nevertheless remains excitable and passionate when it comes to his work.

Manfeldt’s lone friend is Wolf Helius (Willy Fritsch), a young man also keen on the potential of space exploration. He visits the professor one evening, arriving just as another man is angrily leaving the apartment. That man is “The man who calls himself Turner,” as the opening credits state, a dead-eyed villain played by Fritz Rasp, who the same year appeared in G.W. Pabst’s Diary of a Lost Girl. Turner is a master of disguise (cleverly manipulated with some sly cutting from Lang) and a member of a malicious “international financial syndicate” that has caught wind of the rumored moon-gold. Knowing Helius was planning to travel to space, the evildoers offer up an ultimatum: He goes by their orders and in their service or he doesn’t go at all and his work will be destroyed. Helius initially rebukes the participation in a possible “colony of criminals on the moon,” but he is ultimately left with little choice.

Helius had earlier reached out to his assistant, Ingenieur Hans Windegger (Gustav von Wangenheim), who happens to reveal his engagement to Friede Velten (Gerda Maurus), also the object of Helius’ affection, and the trio all embark on the subsequent voyage. Joining them are Turner, Manfeldt (pet mouse in tow—played by Die Maus Josephine, as the credits note), and a surprising stowaway, Gustav (Gustl Gstettenbaur), a young friend of Helius’ who is enamored by science fiction stories.

The business of how and why these individuals get to space is the most interesting part of Woman in the Moon. Some plot points are glossed over, as when it is mentioned that Helius’ unmanned vessel reveals the elements of sustainable life on the moon, while the attitude toward space travel itself is oddly erratic. Friede and Hans show great interest in the voyage, much to the chagrin of Helius, who fears for their safety on the dangerous mission. Yet while the prospect is met with excitement, the decision is also, rather humorously, greeted with a casual calm: “Hans, he’s decided to go to the moon,” says Friede, as if they were going along on a merry jaunt to the countryside. A 36-hour trip to the far side of the moon follows (Apollo 11 took 73), whereupon Hans is immediately ready to return as the vulnerability of their situation sets in and animosity grows, partly based on the now obvious relationship between Helius and Friede and partly based on the intentions of the wicked Turner.

Over the course of its nearly three-hour duration, Woman in the Moon takes its time with the details involved, occasionally at the expense of forward plot progression. Some of this is relevant to the necessity of explanation and validity, and praise goes to Lang for retaining a measured pace of the process in his devotion to getting things as accurate as possible, at least to the best of anyone’s knowledge at that point in history. But when the actual moon landing nears, ostensibly the big moment of the movie, and despite eager exclamations like Manfeldt’s “The moon awaits!” the film stalls somewhat under the weight of the details.

Woman in the Moon is an oddly deceptive film. It starts off reminiscent of earlier Lang work, with a dash of espionage and illicit scheming, but those sequences are of a genre that the film eventually abandons as they become merely a dissipating impetus for getting everyone to space. While it does increase the tension, particularly as Helius finds himself threatened, the criminal repercussions essentially move by the wayside. At the same time, for a film that concerns itself so much with actually getting to the moon, once there, the cosmic surroundings function as a backdrop for relatively conventional drama that has little to do specifically with its setting.

None of this really takes away from Woman in the Moon though. This is a film far more about spectacle and science than it is a reasonable storyline (a storyline that still manages to serve its purpose well enough). And while it is easy to look at a film like this with quaint smugness, amused at what are now obviously antiquated notions of space travel, one has to admire its ambitious scope and respect its attempts to at least provide rationale for the action, something many sci-fi films even today bypass altogether. Besides, not everything was so far-fetched after all; among several examples of what would become commonplace features of actual space travel is the famous first instance of a countdown—in film and in real life.

None of this really takes away from Woman in the Moon though. This is a film far more about spectacle and science than it is a reasonable storyline (a storyline that still manages to serve its purpose well enough). And while it is easy to look at a film like this with quaint smugness, amused at what are now obviously antiquated notions of space travel, one has to admire its ambitious scope and respect its attempts to at least provide rationale for the action, something many sci-fi films even today bypass altogether. Besides, not everything was so far-fetched after all; among several examples of what would become commonplace features of actual space travel is the famous first instance of a countdown—in film and in real life.

Woman in the Moon is not Lang’s best film by far, but it is Lang doing what he did so well, especially in Germany. Though it may get overshadowed by titles like Metropolis (1927) or M (1931), Lang’s next feature, Woman in the Moon is a sophisticated, successful synthesis of action with ideas, suspense with humor, and grand design with minute detail.