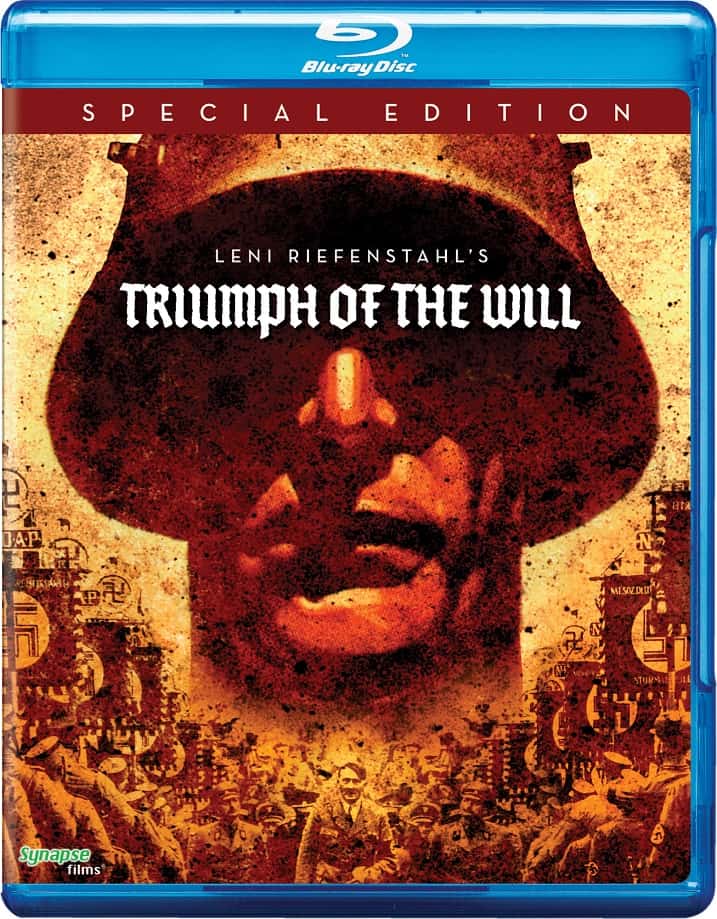

Written by Leni Riefenstahl, Walter Ruttmann, Eberhard Taubert

Directed by Leni Riefenstahl

Germany, 1935

It is never easy to look at Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will as anything other than what Dr. Anthony Santoro quite rightly calls a “supreme propaganda film.” As that, it is nearly unparalleled in the dubious annals of film history. Contributing to its difficulty in terms of analysis, however, is the fact that it is, at the same time, more than simply a notorious document of evil in bloom. For all the troublesome features that recurrently arise through the course of this film—the domineering presence of Adolf Hitler being just one obvious example—this is one remarkably well-crafted motion picture. Its status as the ultimate work of cinematic propaganda is, indeed, a direct result of just how superbly powerful, sadly persuasive, and expertly realized the documentary is, for better or worse.

As opening titles state, Triumph of the Will is the “historical document of the 1934 Congress of the National Socialist German Workers Party,” an annual event lasting Sept. 4-10 in Nuremberg. The project itself was “commissioned by the order of the Führer,” which, of course, helps explain its stress on Hitler’s own superiority and perceived magnificence. Over the span of this recorded jubilee, Hitler travels from place to place giving a variety of oftentimes themed speeches; he promotes Germany’s current transitory state, moving past the suffering of World War I and the resulting devastation toward an ongoing national rebirth, and he touts the country’s economic, industrial, agricultural, and popular accomplishments. Hitler, who was named chancellor just the year prior, clearly saw the film as an ideal introduction of sorts, and subsequently, the film has the tenor of shamelessly effective self-promotion.

While much of Triumph of the Will revolves around Hitler’s beliefs, policies, and his mere existence, the film is not preoccupied by him alone. A wide swath of the German populace is likewise given attention by Riefenstahl and her crew. Women are shown greeting Hitler with a bounty of produce, for example. They appear happy, healthy, and, like so many others, are nearly giddy in their admiration of this new, charismatic leader. They are depicted as maternal figures, caretakers reaping the agricultural products of the fatherland for the benefit of the nation. As Hitler continues to be greeted by throngs of admirers, most of whom scarcely conceal a visible sense of awe, children are also frequently seen, from toddlers looking on in wide-eyed wonder to the exuberant Hitler Youth. This latter group of young men are set up in an encampment on the outskirts of the city. They busy themselves by rough-housing and meticulously preparing for the festivities at hand: exercising, grooming themselves, dressing the part of dutiful native sons. This inclusion of women and children is a slyly manipulative maneuver on the part of Riefenstahl and the powers that be. Unsuspecting audiences at the time surely saw this and shrugged off any dormant wickedness—how could there be with such approving innocence?

While much of Triumph of the Will revolves around Hitler’s beliefs, policies, and his mere existence, the film is not preoccupied by him alone. A wide swath of the German populace is likewise given attention by Riefenstahl and her crew. Women are shown greeting Hitler with a bounty of produce, for example. They appear happy, healthy, and, like so many others, are nearly giddy in their admiration of this new, charismatic leader. They are depicted as maternal figures, caretakers reaping the agricultural products of the fatherland for the benefit of the nation. As Hitler continues to be greeted by throngs of admirers, most of whom scarcely conceal a visible sense of awe, children are also frequently seen, from toddlers looking on in wide-eyed wonder to the exuberant Hitler Youth. This latter group of young men are set up in an encampment on the outskirts of the city. They busy themselves by rough-housing and meticulously preparing for the festivities at hand: exercising, grooming themselves, dressing the part of dutiful native sons. This inclusion of women and children is a slyly manipulative maneuver on the part of Riefenstahl and the powers that be. Unsuspecting audiences at the time surely saw this and shrugged off any dormant wickedness—how could there be with such approving innocence?

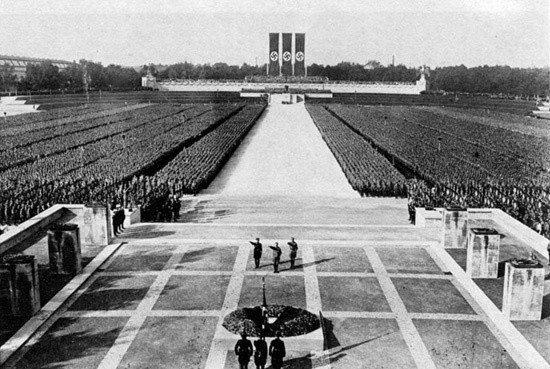

No matter the populace at the center of attention, there is a repeated accent on faces, motions and gestures, and the celebratory display of energetic bodies enacting a sense of togetherness and camaraderie. As Hitler’s magnetism comes through during moments of one-on-one interaction, during which time he intimately greets certain individuals, no doubt leaving inedible impressions on their lives to come, there is nevertheless that which Triumph of the Will is aiming to so prominently endorse, and that which Hitler himself continually emphasizes: the notion of being part of something larger than a singular entity—the 700,000 strong are here as part of a communal unit.

Contrasting the lively, essentially good-natured enthusiasm of the youth is the formal rigidity of the authoritative figures. As we see a who’s who of Nazi officials—Martin Bormann, Otto Dietrich, Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, Heinrich Himmler, et al—they pose and salute and are commonly surrounded by a monumental regimentation of citizen-soldiers. Triumph of the Will is at its most extravagant and, again, frightfully convincing, when Riefenstahl turns her cameras (she employed more than 30) on the pomp and circumstance of the storm troopers and other factions of the National Socialist Party: the costumes/uniforms, the regalia and ornamentation, and the flags and standards all lit and framed to precise effect. Everything these men do and convey is militaristic in nature, from the formations of the youth to the labor force standing at attention with spades in hand like rifles at the ready. For all of this type of soldierly bluster, though, Santoro notes that the Party was not in itself a military institution, but rather an ideological social construct composed military style, with a stress on “quasi-military training.” In any case, the prominent composite of symbolic insignia and the physicality of the people points toward a visual association that would soon be inseparable from Nazism and its devotion to iconography, in its structures, outfitting, and in the idyllic concept of strength, uniformity, and bodily perfection.

Contrasting the lively, essentially good-natured enthusiasm of the youth is the formal rigidity of the authoritative figures. As we see a who’s who of Nazi officials—Martin Bormann, Otto Dietrich, Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, Heinrich Himmler, et al—they pose and salute and are commonly surrounded by a monumental regimentation of citizen-soldiers. Triumph of the Will is at its most extravagant and, again, frightfully convincing, when Riefenstahl turns her cameras (she employed more than 30) on the pomp and circumstance of the storm troopers and other factions of the National Socialist Party: the costumes/uniforms, the regalia and ornamentation, and the flags and standards all lit and framed to precise effect. Everything these men do and convey is militaristic in nature, from the formations of the youth to the labor force standing at attention with spades in hand like rifles at the ready. For all of this type of soldierly bluster, though, Santoro notes that the Party was not in itself a military institution, but rather an ideological social construct composed military style, with a stress on “quasi-military training.” In any case, the prominent composite of symbolic insignia and the physicality of the people points toward a visual association that would soon be inseparable from Nazism and its devotion to iconography, in its structures, outfitting, and in the idyllic concept of strength, uniformity, and bodily perfection.

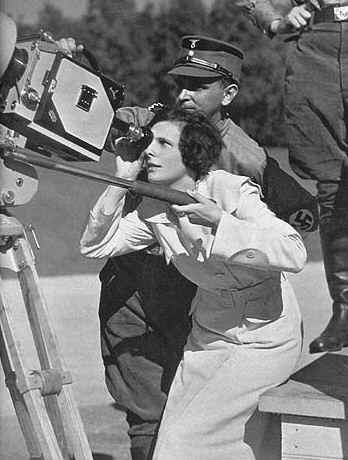

In his instructive commentary track for the newly released Synapse Films Blu-ray of Triumph of the Will, Santoro regularly acknowledges the phenomenal cinematography of the film. Essentially given creative carte blanche and a wealth of equipment, Riefenstahl’s direction calls for camera placement towering above on elevator-like contraptions, sweeping on cranes, traveling amidst the crowd on vehicular mounts, and low and high angles that emphasize not only the literal size and scope of the congress, but the symbolic stature and significance of Hitler and the occasion in general. As much as the film and the ceremonies might have been staged, in that Hitler and his crew, with Riefenstahl, orchestrated the happenings to optimum effect, Triumph of the Will is a remarkable achievement in set construction, organization, and technical capability. There are some sequences, such as the “sea of flags,” that attain an astonishing level of abstraction, where the seemingly authentic nature of the documentary melds into the realm of hallucinogenic imagery. Though color stock was available, both Hitler and Riefenstahl preferred black and white, and for its contemporary purposes, to say nothing of its current historical relevance, this was a wise choice. In the tradition of cinematic Germanic masterworks like Metropolis (1927) and Faust (1926), it is as if everything Riefenstahl records could only have been fabricated as in a work of extravagant fictional filmmaking, and maybe to a certain extent it all is a work of contrived manipulation. But amazingly, what we see really did happen.

Though this week-long ceremony may have been designed for the benefit of, and as a testament to, the German people, it is quickly evident that what transpires is more accurately an ode to only one man. We may see diverse passionate spectators, but when they are looking up with that fervent sense of admiration and marvel, it is directed at Hitler and Hitler alone. As Santoro puts it, Riefenstahl gave the “cult of Hitler” form. Fortunately, as he also points out, for all of its expenditure in terms of production, Triumph of the Will suffered from relatively meager marketing, thus limiting the distribution of the film and subsequently lessening the international spread of its rhetoric. Though the tone of the language here is predictably political and generally innocuous (without the beneficial knowledge of hindsight, that is), it would soon become explicitly, intoxicatingly toxic.

Though this week-long ceremony may have been designed for the benefit of, and as a testament to, the German people, it is quickly evident that what transpires is more accurately an ode to only one man. We may see diverse passionate spectators, but when they are looking up with that fervent sense of admiration and marvel, it is directed at Hitler and Hitler alone. As Santoro puts it, Riefenstahl gave the “cult of Hitler” form. Fortunately, as he also points out, for all of its expenditure in terms of production, Triumph of the Will suffered from relatively meager marketing, thus limiting the distribution of the film and subsequently lessening the international spread of its rhetoric. Though the tone of the language here is predictably political and generally innocuous (without the beneficial knowledge of hindsight, that is), it would soon become explicitly, intoxicatingly toxic.

Once Riefenstahl was able to whittle down Triumph of the Will to a manageable length, using a very small percentage of what was actually shot, the film went on to win a documentary award at the 1935 Venice Film Festival and was there nominated for the “Mussolini Cup” for Best Foreign Film. Yet in viewing this film today, there is no way around the fact that everything about it is immensely disturbing. As much as possible, though, it does deserve attention for its artistic merit, apart from its disconcerting content. Riefenstahl was an unquestionable talent, as a captivating actress and imaginative director, and though a project like Triumph of the Will is problematic at best, there can be no denying that what this film sets out to do it does very well—frighteningly well—and much of that derives from its characteristics as a technically accomplished, albeit extremely challenging, work of the cinema.