The French gave us the word “demimonde” – literally, half the world. But what it has come to mean in English, or so says Webster, is “a distinct circle or world that is often an isolated part of a larger world.”

Storytellers have always held a fascination with the dark side of human nature; that part of the psyche which is normally restrained and leashed, taught to be obedient, held in check – as Conrad wrote in Heart of Darkness – by the reproving looks of our neighbors. After all, what was Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde but a probing of that other, id-driven half and the entrancing appeal of doing what one wants instead of what one should.

Film is no different than literature, and from its beginning the movies have produced a rich vein of stories about society’s fringe dwellers, those who operate by necessity, desire, or sociopathic carelessness beyond the realm of the law abiding. Often in the movies, they are criminals, pure and simple: thieves, killers, brutes.

But the blossoming of film noir in the 1940s and 1950s seemed to uncork something among more audacious moviemakers; an interest not simply in the lawbreaker, but a creature who lived in a gray place between the socially acceptable and the outright criminal. Perhaps many moviemakers – people operating out of the mainstream of American life themselves – identified with these rogues and hustlers for whom the social norms didn’t apply.

This became especially true in the 1960s and 1970s. It was a time when American movies were at their most daring, and moviemakers were being granted a then unprecedented creative freedom.

It was also a time of great social upheaval and social rebellion, and the maverick, the rebel, those who lived beyond the rules in a shadow world which often had few of its own, became an attractive, intriguing figure.

Some were criminals, some only semi-so, but all lived in a place most of us suspected existed…but never ourselves saw.

Herewith some of the best portraits from the 60s/70s of that demimonde and its most colorful denizens:

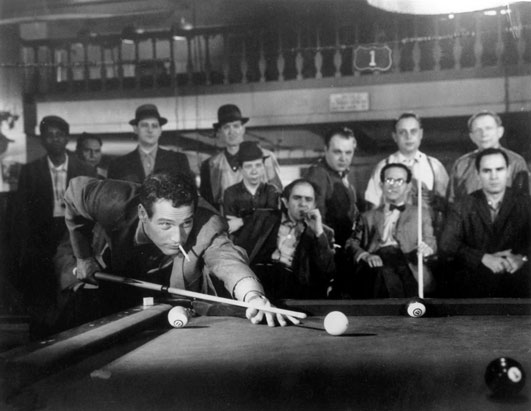

The Hustler (1961). Directed by Robert Rossen. Written by Rossen and Sidney Carroll, adapting the novel by Walter Tevis.

Throughout his career first as a screenwriter than as a writer/director, Rossen had a fascination with characters operating where the normal rules of behavior didn’t apply i.e. the psychotic sea captain of The Sea Wolf (1941), soldiers trying to survive “just another day” in WW II in A Walk in the Sun (1945), the amoral political kingpin of All the King’s Men (1949), and the strangely corrupt heroes of They Came to Cordura (1959). But he never captured the idea as well or in so exquisitely seamy a fashion as in The Hustler.

Paul Newman is Fast Eddie Felson, a pool hustler on the come looking to take down the king of the pool rooms, Minnesota Fats (Jackie Gleason). Felson is broken by Fats in a brilliantly staged opening pool duel, then scuffles around trying to put together a big enough stake to take on the Fat Man once again.

It’s a movie of bus station bars and cheap saloons, wheelers and dealers, and the kind of smoke-filled dives where a misplaced hustle gets your thumbs broken. And somewhere in all the cigarette smoke and all-night pool contests Felson finds – much to his own surprise – there’s still one bit of heart to him.

Aided and abetted by cinematographer Eugene Shuftan and the great editor Dede Allen, Rossen gives the bookending pool marathons an electricity even Martin Scorsese couldn’t quite match in his more upscale sequel, The Color of Money (1986), but then Scorsese’s movie is in color and set when pool had become – shudder – respectable. As no other movie before or since, Rossen’s flick captures the seedy sexiness of old time, men-only pool halls and the men who made their disreputable living and sought an even more disreputable glory off a green felt tabletop.

Taxi Driver (1976). Directed by Martin Scorsese. Written by Paul Schrader.

Enough has been written over the years about Taxi Driver that anything said here could only be redundant. Suffice to say that Scorsese/Shrader’s tale of a disaffected, totally socially disconnected Viet vet prowling the scummy streets of 1970s New York is, for many, the ultimate outsider’s story.

Photographed with a they-only-come-out-after-dark neon-lit gloom by the brilliant cinematographer Michael Chapman, Taxi Driver captures New York when it was at its worst; it’s an alien nightscape populated almost entirely by the bizarre, the deadly, and the perverse.

It’s not for all tastes, and may make you want to take a long, hot shower afterward, but for those not weak of heart, turn down the meter flag and take a Boschian ride through downtown hell.

Midnight Cowboy (1969). Directed by John Schlesinger. Written by Waldo Salt adapting the novel by James Leo Herlihy.

From the 1960s into the 1980s, the Times Square/42nd Street area of New York was, sadly, an internationally recognized image of urban decay and decadence. Tawdry, dirty, filled with the lava-lamp glow of neon and flickering grindhouse and porn theatre marquees, and populated by the most garish of hookers and hustlers, The Deuce – as the natives called 42nd Street – was the beating dark heart of what, at the time, seemed a dying, utterly corrupt city.

And amidst the abandoned tenements and curbside heaps of trash, John Schlesinger and Waldo Salt told a surprisingly touching story of human connection. Even those at the bottom, they said, even the utter, most self-deluded losers get lonely and hunger for a friend.

Jon Voight is one of the self-deluded, a young Texan who comes to New York thinking he can score as a stud. And Dustin Hoffman, in one of his early, signature roles (“I’m walkin’ heah!”), is one of the losers. There’s no driving plot; just the day-to-day hustles they pull off to barely stay alive in a city which seems some sort of urban Darwinesque exercise in survival of the fittest, but it’s memorable, melancholy theme, its time capsule images of a New York long gone (some might say thankfully), and its bittersweet ending will hang with you for days.

Footnote: Midnight Cowboy is the only X-rated movie ever to win the Academy Award for Best Picture (the movie was later re-rated R in 1971).

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974). Directed by Sam Peckinpah. Written by Peckinpah and Gordon Dawson from a story by Peckinpah and Frank Kowalski.

There are those, like Roger Ebert, who consider Alfredo Garcia among the controversial director’s best work and a genuine piece of cinematic art. There are others, like Michael Medved, who consider it among the worst movies ever released by a major studio.

Either way, I think anyone would agree this is easily one of the most audacious movies, with the possible exception of Taxi Driver, to go into the American commercial mainstream.

Warren Oates is Benny, a down-at-the-heels piano player in a cheesy tourist bar somewhere in Mexico. He has a chance at a $10,000 payday when he learns there’s a bounty on the head of Alfredo Garcia for knocking up the daughter of a mysterious jefe’s daughter. Benny learns from his hooker girlfriend (Isela Vega) that Garcia is already dead, killed in an automobile accident. They have only to drive to Garcia’s hometown in the Mexican boonies to retrieve his head. But any quest so perverse and morally corrupt can come to no good end, and this one is no exception.

Alfredo Garcia is about losers holding on to society’s lowest rung by their fingernails, being given a one-time-only Faustian deal to climb up. By turns disturbing, ethereal, nightmarish, and occasionally even touching (Oates and Vega have a roadside scene which may be one of the most affecting in all of Peckinpah’s movies), Alfredo Garcia – love it or hate it – is one of a kind.

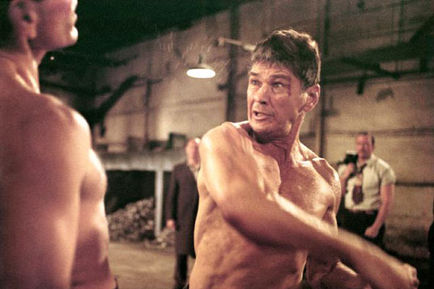

Hard Times (1975). Directed by Walter Hill. Written by Hill, Bryan Gindoff, Bruce Henstell.

This forgotten first feature by Hill is easily his best. It has all the entrancing simplicity of a barroom ballad, and much of the same flavor.

Charles Bronson is a drifter who comes to Depression-era New Orleans and hooks up with hustler James Coburn to make some money in backroom bare-fisted fights.

It’s a lean, almost wisp of a story, told with an appropriate terseness and a clean, Spartan style Hill rarely matched afterward. Hill gets more mileage out of Bronson’s weathered face than other directors can get out of a page-long monologue.

When asked what he does for a living, Bronson plainly replies, “I knock people down.” And that’s how the movie works: plain, direct, and on target.

The Cincinnati Kid (1965). Directed by Norman Jewison. Written by Ring Lardner, Jr., Terry Southern, adapting the novel by Richard Jessup.

What The Hustler was to pool, The Cincinnati Kid is to poker.

In another tale set in Depression-era New Orleans, Steve McQueen is the heir presumptive in the world of backroom high-stakes poker, looking to topple The Man: Lancey Howard (Edward G. Robinson). Not quite as grim as The Hustler, nor as period flavorful as Hard Times, Cincinnati Kid is still a terrific piece of hustlers-on-the-make entertainment.

Part of its rich feels comes from a being perfectly cast from McQueen and Robinson down to the smallest parts (filled by such great character actors as Jack Weston, Jeff Corey, Milton Selzer, among others).

And Jewison manages the impossible: he turns the static sit-down of a days-long poker contest into an edge-of-seat third act fraught with suspense and an explosive climax. Less disturbing than most of the movies on this list but one of the most fun watches, deal yourself in.

The Flim-Flam Man (1967) Directed by Irvin Kershner. Written by William Rose, adapting the novel by Guy Owen.

Long before The Sting (1973) and the elaborate cons of the Ocean’s 11 movies, there was George C. Scott flim-flamming his way across the small towns of the American rural south hustling a living off small, deft cons and preying on the greed and foibles that seem to be an inherent part of the human design. Scott takes a young Army deserter under his wing (Michael Sarrazin) who begins to despair of his mentor’s constant success.

“You can’t cheat an honest man,” Scott rationalizes, suggesting that – as he proves time and again – there are no honest men, but Sarrazin can’t let himself go there.

“I gotta believe in somethin’.”

Perhaps a bit sentimental at times, but great fun and with a wonderful sense of place, it’s not a bad antidote for the more grim entries on this list.

As a matter of fact, I can send you a DVD right now. All I need is access to your checking account… Oh, come on, you can trust me.