*Exclaimer: Please don’t read this if you haven’t seen Inception, The Empire Strikes Back, Planet of the Apes, The Wizard of Oz, Saw, Gone With the Wind, Casablanca, The Usual Suspects or The Sixth Sense

–

As a probable testament to my poor academic acumen, I cannot, in good memory, recall the particulars of the situation I’m about to describe for you. I don’t remember the course, the tutorial leader, or the topic at hand, but I do remember it was an early morning class on a balmy winters day. In my usual bleary-eyed state of apathy, I resigned myself to a self-assigned seat at the back, content to make up the numbers and to pick up my arbitrarily appointed participation marks.

As the class commenced its usual schedule of speculative faff and conjecture, I commenced my own schedule of affairs: looking at people when they’re not looking back and looking away when they sometimes do. To be sure, dear reader, this practice would seem well odd to you, but keeping my eyes open and pretending to pay attention was tantamount to participation (see previous paragraph). Besides, I’m willing to wager a hefty sum in favour of the idea that other people do it as well, and, in my own impudent kind of way, I had gotten quite good at it.

Scanning the room to find a noteworthy point of interest, to which I mean somebody attractive, I noticed a girl sitting across the room from me. The expression on her face is one I’ll never forget.

As a stark contrast to my own, her disposition could be best described as a perpetual mood of agitation. Sitting bolt upright with fingers digging into her knees, her demeanor suggested one of great offense, and yet, by her expression, her posture also suggested a sense of rigid self-defense.

Mouth slightly ajar and looking around with what can only be compared to as a disconcerting Kubrick stare, I was snapped out of my own nebulous trance by the sheer curiosity of her appearance. Imagine a Buckingham Palace guard, with the face of Edvard Munch’s The Scream, watching a game of tennis and this is what the girl looked like.

In order to satiate my sudden interest in her discomfort, I also looked around the room, looking for the source of her searing glare. After a quick appraisal of the class, I narrowed it down to two people; a young lad, with an ironic moustache and a Toronto Maple Leafs toque, and another young lad, whose face I couldn’t see because he was sitting right in front of me.

As I focused in on them more, and my morning cup of coffee finally started to kick in, I suddenly noticed they were talking; nay, they were arguing. Like I said, I don’t recall what the original point of disagreement was, but it was early winter of 2010, so they were talking about what everybody else was talking about, the vogue topic of the year: Inception.

I won’t bother to delve into the specifics of the conversation, but it’s suffice to say that the heated tête-à-tête was indeed that – specific. The bloke in front of me was arguing for the idea that the whole damn thing was a dream, while the Leafs fan took the counter position. In my opinion, the latter, like all Leaf fans, was on the losing side.

To prove their respective points, each would bring up specific scenes, scenarios, lines of dialogue and references from the film, elucidating their point of view with sharp, trenchant detail. All around me, the class was divided into two groups, and I could tell which side any given person was on by noting when they shook their head in agreement and when they shook it in disapproval. The only exception was that one girl.

As I refocused my attention back on her, I realized that, every so often, she would spring up ever so slightly, leaning forward in an almost half jump from her seat, and let out a barely audible whimper. From that I could tell that she had something to say, something to add to the discussion, but as everyone was deeply entrenched in his or her own predisposed perspective, she was hardly noticed at all.

When the class finally ended and as nothing was resolved, as per usual in academic circles, I decided to take a chance. I decided to go up to her and ask her what she thought about the movie, listen to her and have a conversation because, dear reader, women like nothing more than to be noticed, especially when they’ve been ignored the whole day. And as per usual, like a Leaf fan, I would end up on the losing side.

I caught up with her just as she was about to leave the room and said, “Hey, I saw you in class (a grand understatement) and you looked like you had something to say. What did you think about the –”

Before I could finish, she cut me off in abrupt, pent up anger. Now, confronting me alone and no longer outnumbered, she finally mustered the courage to tell me what she really thought, and tell me she did.

“What do you mean, “what do I think”? What should I think? I haven’t even seen the movie yet! I was going to see it when it came out on DVD! I was going to tell you all to stop but nobody would let me! Now it’s ruined for me! You ruined it for me!”

For your consideration, dear reader, I haven’t quoted her verbatim. I left out a host of effing and jeffing, but after her vociferous cloudburst of discontent, I was rooted to the spot, unable to move as I watched her storm out of the building.

I stood there thinking, surely, Inception was the most anticipated movie of the year. The film’s reputation must’ve preceded it, especially after all the critical and box office success. She must have seen it.

But she hadn’t. No matter how hard I tried to absolve myself of the guilt I was feeling, I knew I couldn’t. I knew, by not interjecting and by becoming a by-standing participant in the debate, by not even considering the idea that someone else hadn’t seen it, no matter how minute those chances are, I was allowing the debate to continue.

I allowed the crucial details of the movie to be discussed in front of a person who didn’t want it to be discussed, and our collective preoccupation in our selfish pursuits (mine being different from everyone else’s) overshadowed her unavailing attempt to stop it. If it wasn’t for those arbitrarily appointed participation marks, I’m sure she would’ve left the room in protest.

In a sense, I did spoil it for her. I should’ve known better because, for most of my life, the exact same thing happened to me and on more than one occasion. People have been spoiling movies for me since I can remember, and the buck should’ve stopped at me. And in case you were wondering, reader, I didn’t get her number.

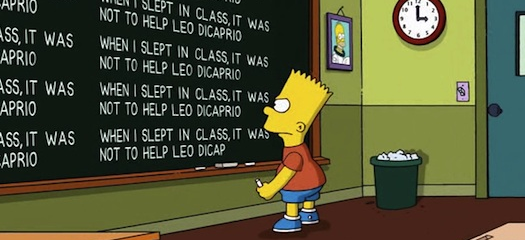

Before I was old enough to watch R-rated movies, let alone enjoy them, my favourite pastime was to sit myself in front of the telly and watch my favourite show, The Simpsons. As a kid, I would come home from school to watch Homer’s buffoonery, Bart’s tomfoolery, and Burns’ humbuggery, and it wasn’t until I was much older did I come to understand the nuances of the programme.

Before I was old enough to watch R-rated movies, let alone enjoy them, my favourite pastime was to sit myself in front of the telly and watch my favourite show, The Simpsons. As a kid, I would come home from school to watch Homer’s buffoonery, Bart’s tomfoolery, and Burns’ humbuggery, and it wasn’t until I was much older did I come to understand the nuances of the programme.

In almost every episode I could think of, The Simpsons would throw in a movie reference into the plot. At the time, I was too young to fully understand what it meant or what movie it came from, but, in my own childish way, I nonetheless understood that it was a reference.

The most vivid memory of a Simpsons movie reference I can remember is when Homer, in Season 3 Episode 12, in a flashback sequence, goes to the pictures with Marge. They happened to be watching The Empire Strikes Back, and while walking out of the theatre after the movie was finished, Homer, in his usual ignorance, exclaims, “Wow, what an ending! Who’da thought Darth Vader was Luke Skywalker’s father?” in front of a line of people waiting to see it.

The irony of this joke is that, although the show was making a humorous statement about Homer spoiling a movie for a bunch of people, the show had, in its own way, spoiled the movie for a bunch of people. Me included.

D’oh.

I was ten when I first saw that episode, and for me, Star Wars was something I had only heard of in passing reference. Movies were not an obsession of mine, not yet anyway, and the only movies I watched were my parents’ DVD’s from Hong Kong.

In terms of reputation, Stars Wars certainly had one that preceded it. The phrase “Luke, I am your father” and its many variations have become ubiquitous in everyday parlance, and I’ve come to associate it with the movie even before I had seen it. So imagine my disappointment when I finally did.

One night, on the behest of my fellow film buffs, I hunkered down and watched the entire original trilogy in one sitting (they advised me against the prequels). As the story unfolded in the magical way that it does, I couldn’t help myself from thinking that Darth Vader was indeed Luke’s father.

Like in Inception, this idea was buried deep within my subconscious. When Vader killed Obi Wan, I thought, “Luke’s father killed Obi Wan”. When Vader froze Hans Solo, I thought, “Luke’s father just froze Hans Solo”. When the time came for the big reveal, I was expecting it. I knew it was coming, and the result was anticlimactic instead of revelatory, an experience in bathos and not pathos. I felt the exact opposite effect it was intending and I assume that this was the case for most people that watched Empire after 1980.

“Oh thank you, Mr. Blow-the-picture-for-me”.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gMnG3gOqigE

This wasn’t the last time that The Simpsons or someone or another ruined the climax of a movie for me. Before I saw Planet of the Apes, I already knew it was earth all along, before I saw The Wizard of Oz, I knew there was no place like home, and before I saw Saw, I knew the guy wasn’t coming out with both feet.

When I was watching Gone With the Wind, I wondered if Vivien Leigh’s Scarlett O’Hara was going to end up with Clark Gable’s Rhett Butler only to remember that, in the end, Gable is going to say, “Frankly dear, I don’t give a damn” to her.

The same thing happened to me when watching Casablanca, wondering if Humphrey Bogart’s Rick and Ingrid Bergman’s Ilsa will reunite, only to remember that Bogart will say, “we’ll always have Paris”.

Before watching The Usual Suspects, I already knew who the real Keyser Söze was, and before watching Fight Club, I already knew who Tyler Durden was as well.

And worst of all, I knew that Bruce Willis was dead the whole time before I saw The Sixth Sense. I don’t say ‘worst of all’ meaning that I thought The Sixth Sense was better than Gone With the Wind or Casablanca – far from it. By ‘worst of all’, I mean that this single moment of disclosure was key to the overall appreciation of the film.

Even though I knew Vader was Luke’s dad and that the ‘alien’ planet was really earth and ad nauseam, I still adore and recognize the greatness of these film. In The Sixth Sense, everything relied on the fact that you’d be surprised at the end. Initially, it worked because, otherwise, people wouldn’t have talked about it, it wouldn’t have become a social staple in conversations, and it wouldn’t have been ruined for most 21st century audiences.

As disappointing as these spoilers were for me, I should note that it does a massive disservice for the writers. Consider this, dear reader: M. Night Shyamalan, who wrote and directed The Sixth Sense, must’ve spent hours upon hours to craft an intricate and deceptive piece of subterfuge. He must’ve wrote and re-wrote countless drafts of a script in order to conceal the twist and make it unpredictable. In the end, he did, and audiences reacted in a way that it hasn’t since Les Diaboliques or The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

In his next features, people were expecting Shyamalan to shock them once again; and to his detriment, he tried. His follow-up attempt, Unbreakable, was a marginal success in this regard, but none of his subsequent films have ever replicated the sense of awe and gleeful bewilderment that surrounded The Sixth Sense. A discussion of Mr. Shyamalan’s filmography usually goes as follows: “He hasn’t done a good film since The Sixth Sense. Remember that one, when Bruce Willis was dead the whole time?”

He was probably conscious of the fact that people were talking about his twist endings, so he made them more contrived and unbelievable, hoping to surprise us. He never has, in a meaningful way, and he never should’ve tried. But since everyone was talking about how great the fact that “Bruce Willis was dead the whole time” was, he probably couldn’t help it.

The reason why a certain moment is so memorable and so deeply moving is because it is predicated on a careful accumulation of context and circumstances.

In Casablanca, Rick and Ilsa once had a fleeting romance while they were both in Paris. Without notifying Rick, Ilsa clandestinely departs when she learns that her presumed dead husband survived the Nazi concentration camp. When they meet again in Casablanca, and Ilsa tells Rick what happened, the two reconcile, only to have the war stand in their way. Choosing honour and nobility over love, for the first time in his life, Rick urges Ilsa to go with her husband, thus helping in the war effort against the Nazis, and before they part one last time, he says, “We’ll always have Paris”. This statement alone evokes feelings of forlorn pathos and as a way to capture, if only in words, the peace and tranquility of antebellum Europe.

In Gone With the Wind, we see Scarlett act like a harridan for almost four hours, so when Rhett says he no longer gives a damn, the moment is imbued with an ethereal mix of catharsis and comeuppance.

In all cases, the writers use their abilities to craft a rich and captivating story that accrue into a crescendo of emotions, usually manifesting in a single line or moment of immortality. By knowing this moment beforehand, we are essentially robbed of this visceral reaction because we don’t feel it organically.

Sure, we might still understand the context behind them, as I do, but it doesn’t have the same emotional impact as it did for viewers watching it Tabula Rasa. I’ll never know what it’s like to watch Star Wars in 1980, or Casablanca in 1942, or even The Sixth Sense in 1999.

To spoil a movie for others because we assume they’ve seen it, or because the movie in question has been around since time immemorial, is callous and tactless. There shouldn’t be a statute of limitations for spoilers. Just because some of us have experienced a moment of transcendent cinema, or if some of us haven’t, doesn’t mean we should deprive others of the same raw and immaculate opportunity to.

I don’t want to impose some kind of amendment to whatever constitution your country has or hasn’t, but I think it would be pragmatic to show some kind of prudence when discussing movies. A film can sometimes go beyond the confines of its medium and establish itself as a staple in various areas of discourse, but it still doesn’t mean they’re ubiquitous to others.

For example, reader, did you know that the “subjectivity of perception on recollection, by which observers of an event are able to produce substantially different but equally plausible accounts of it” is called the Rashomon effect?

Rashomon is a classic film, but its exalted position in certain academic circles doesn’t mean we can talk about it with indifferent regard to the people listening. People, like the girl I mentioned, often don’t speak up when they haven’t seen a ‘classic’ movie being discussed, often because of the supposed embarrassment that stems from not having seeing them.

In fact, in a recent poll, 30 percent of respondents say that they’ve lied about seeing The Godfather, 13 percent for Casablanca, 11 for Taxi Driver and 9 for 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The magic of the movies come from the feeling of being mesmerized and enchanted by the experience. By knowing how the trick will end, or how the magician does it beforehand, the magic is ostensibly gone, or at least made more cerebral and less affecting. Those who were fortunate enough to be spellbound the first time around shouldn’t rob others of the same magic; instead, they should allow others to discover them on their own accord, or with a subtle nudge in the right direction.

I know that there are some of us out there who are dead chuffed to be esoteric, those who want to spoil the experiences of others because they feel like doing so will endow upon them a false sense of superiority and obdurate elitism.

I know that old habits die hard and that our passion for movies will sometimes be counterintuitive for our collective admiration of the art.

I also know that this article may never leave the friendly confines of this site and that many movie-lovers out there with the same reverence and respect for cinema and its universal appeal, as I do, will never read this.

Frankly, my dear reader, I don’t give a damn. It just had to be said. If I had said it earlier I wouldn’t be single right now.

– Justin Li