Ingrid Bergman’s romance with Italian filmmaker Robert Rossellini was always destined to be a tabloid sensation. Both were international stars in their own way, both were married to other people, and the suddenness of their relationship – on the set of Stromboli, their first film together – coupled with Bergman’s subsequent pregnancy (their son was born before Stromboli even came out), made for a story too compelling for any self-respecting (or self-loathing) entertainment journalist to ignore. Yet unlike most such things, that nugget of intrigue has stuck with them even amongst the most ardent cinephiles today. It’s a facet impossible to ignore, and seems entrenched in analyzing their legend and work.

Why? Well, the reason is fairly simple: she lost it at the movies. It was a screening of Rossellini’s astounding Rome, Open City and Paisan that so moved her to contact him, expressing her admiration and hoping they could eventually work together. It wasn’t his success or fame or acclaim or anything else; she just loved his movies. We might not all go so far as she, but that’s a feeling to which a great many of us who love the movies can relate. You so deeply connect to a film that you become intrinsically bound to it, and it to you, and you feel you understand something profound and beautiful not only about art and the world it represents, but about its maker, perhaps in ways you cannot fully articulate. It’s a hell of a thing to say you’ll travel to a foreign country and work with a filmmaker whose language you do not speak. “If you need a Swedish actress who speaks English very well,” she wrote, “who has not forgotten her German, who is not very understandable in French, and who in Italian knows only ‘ti amo,’ I am ready to come and make a film with you.”

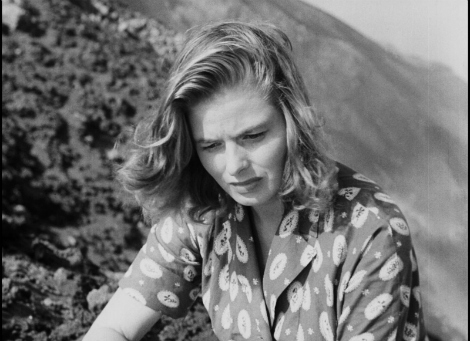

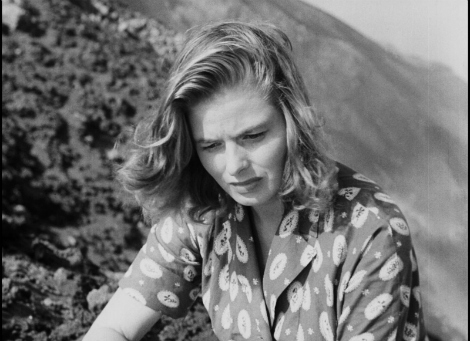

Rossellini’s response was considerably more elaborate, passionately explaining the scenario he envisioned for them to build into the film that would become Stromboli. In his letter, he explains that he does not prepare a scenario (“scenario,” in Italian, is closely related to “screenplay”), instead working from a foundational idea and general sense of story trajectory, only to let the emotion of the thing carry him from there. He said he’d been thinking on the concept, inspired by a woman he saw while driving past a displaced persons camp, and the story he lays out is quite close to that of the finished film. Stromboli is a mix of social realism and religious allegory – in other words, quintessential Rossellini – and it contains the best work Bergman ever did. Her character, Karin, hopes to build a new life for herself by marrying a simple Italian fisherman, but finds their way of life, from the poverty to the manner of dress to numerous customs, impossible to live with, and the ways she tries to wiggle herself free from the situation are at turns wrenching, pathetic, heartbreaking, and repulsive. She’s a fully realized character, deeply flawed and totally sympathetic.

The two ends of this are split off in the films that follow, and which are represented, along with Stromboli, in The Criterion Collection’s recent Blu-ray box set, 3 Films by Roberto Rossellini Starring Ingrid Bergman. Europe ’51 explores the more spiritual side of their collaborations, nearly raising Bergman’s character, a upper-class mother whose grief over her son’s death leads her to dedicate her life to the least fortunate around her, to saint-like status, while being something of an advocate of socialism, if not outright communism. (You don’t see that too often.) Journey to Italy is more relationship-focused, concerning an English couple (Bergman and George Sanders) who are forced to examine their straining relationship while selling a recently-inherited property in Italy.

All three are immense achievements on their own; when viewed collectively, they are astounding. Two immensely talented artists at the height of their creativity and audacity, willing to push not only the medium forward, but also notions of nationality, social responsibility, sexuality, and complacency. Two people whose romance was in many ways central to their work, yet whose films never felt like vanity projects or merely a way of representing their affection for one another. These are tough, mean projects full of doubt, fear (in fact, Fear was the name of one of their films, a very good one sadly not present here), regret, hopelessness, and all manners of looking at faith.

Journey to Italy has long been a staple of international cinema, regularly placing on best-of-all-time lists, including the 2012 edition of the standard-bearing Sight & Sound (not to be confused with this website) poll, where it placed 41st. Stromboli and Europe ’51 have not been as fortunate, in large part because none of them were all that available in the United States. (On a personal note, I had a professor in college who had some imported copies from which she showed clips, but I only caught these films when TCM happened to be airing them several years back.) Now that anyone can go out and buy, rent, or borrow them, might their reputations improve? The floodgates are continuously being ever more opened on cinematic history, or at least that to which we have access. Criterion has changed the game before, many times over, in crafting high-profile releases of neglected, but extraordinarily important films. That these three should be so fortunate is only fitting.

— Scott Nye