(Celebrating award week with a look at one of Oscar’s most notable champions: The French Connection. Thirty-nine years ago, Connection — besides being one of the biggest hits of the 1970s – was the top winner at the Academy Awards walking away with gold for Best Picture [collected by producer Phil D’Antoni], Director [William Friedkin], Actor [Gene Hackman], Adapted Screenplay [by Ernest Tidyman], and Editing [Gerald Greenburg].)

So says Sonny Grosso, and it is a screen icongraphy he has worked hard to change. Grosso-Jacobson Communications has produced over 750 hours of programming for network and premium and basic cable television in its thirty-odd years. Though its output has run from Pee Wee’s Playhouse to adventure fare like Counterstrike, the most acclaimed of the company’s offerings have been true-life policier TV movieslike Out of the Darkness (1985), the story of the breaking of the “Son of Sam” case; Trackdown: Finding the Goodbar Killer (1983); and A Question of Honor (1982), based on Grosso’s book Point Blank (Grosset & Dunlap, 1978), about mishaps and tragedy in a police corruption investigation gone bad. “I try to show in movies what a cop’s life is all about.”

His commitment is understandable once you know that before getting into television, Sonny Grosso spent 20 years with the New York City Police Department. He reached the rank of first grade detective after just three and a half years in the bureau; faster than anyone in the history of the Department. Along with partner Eddie Egan, he broke one of the biggest narcotics smuggling rings in the annals of American law enforcement in the early 1960s. The case would come to national attention with author Robin Moore’s 1969 bestselling account of the case, The French Connection.

When movie rights were acquired by 20th Century Fox, Grosso and Egan were both hired on as consultants to the project. Though the movie would be a fictionalized telling of the story, both detectives saw it as their job to exact a level of authenticity from the filmmakers.

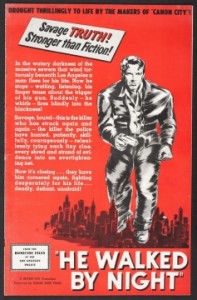

The movies, according to Grosso, have only rarely gotten the picture of cops right. After those early days when the hoods were the sympathetic characters, there followed a more positive image in the  1950s which Grosso credits to Jack Webb. Webb had had a supporting role in a 1948 thriller, He Walked By Night, and been quite taken by the picture’s semi-documentary approach and its attempt to realistically render a police investigation and the professionals who carried it out (thanks to director Alfred L. Werker and an uncredited Anthony Mann, and screenwriters Crane Wilbur, John C. Higgins, and Harry Essex). Many of the stylistic tropes of the movie – the flat, narrative voice-over, realistic plot based on a true-life case, clipped dialogue, accurate depiction of police procedure and techniques – all found their way into Webb’s consequent creation, Dragnet, a series which first premiered on radio, then found huge success on television.

1950s which Grosso credits to Jack Webb. Webb had had a supporting role in a 1948 thriller, He Walked By Night, and been quite taken by the picture’s semi-documentary approach and its attempt to realistically render a police investigation and the professionals who carried it out (thanks to director Alfred L. Werker and an uncredited Anthony Mann, and screenwriters Crane Wilbur, John C. Higgins, and Harry Essex). Many of the stylistic tropes of the movie – the flat, narrative voice-over, realistic plot based on a true-life case, clipped dialogue, accurate depiction of police procedure and techniques – all found their way into Webb’s consequent creation, Dragnet, a series which first premiered on radio, then found huge success on television.

“That ‘Just the facts, Ma’am,’ kind of thing, I liked it,” says Grosso. “I liked Dragnet. But everybody I knew said, ‘I don’t know any cops like that!’”

Dragnet may have rehabilitated the image of the policemen Grosso had grown up with, but it was a sanitized portrait nonetheless. When Grosso met with the young tyro who’d landed the job of directing the movie version of The French Connection, William Friedkin, Grosso gave him his mandate. “I told Billy, ‘If you can show what cops are like below the surface, you don’t have to make them pretty or nice, as long as you get across why we do what we do.’” The detective said something similar to Gene Hackman who was playing Popeye Doyle, the character based on Eddie Egan: “Get to the honesty of it.”

Dragnet may have rehabilitated the image of the policemen Grosso had grown up with, but it was a sanitized portrait nonetheless. When Grosso met with the young tyro who’d landed the job of directing the movie version of The French Connection, William Friedkin, Grosso gave him his mandate. “I told Billy, ‘If you can show what cops are like below the surface, you don’t have to make them pretty or nice, as long as you get across why we do what we do.’” The detective said something similar to Gene Hackman who was playing Popeye Doyle, the character based on Eddie Egan: “Get to the honesty of it.”

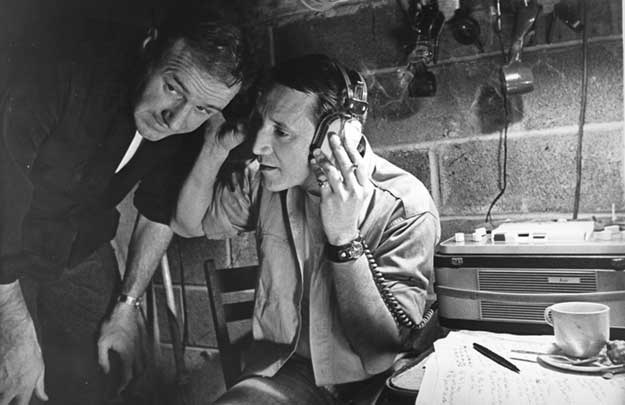

To that end, Grosso and Egan had regular input into Ernest Tidyman’s developing screenplay, and also spent three weeks with Hackman and Roy Scheider (who, in an Oscar-nominated turn, would play the character based on Grosso). When Hackman and Scheider had been told they would be meeting with the detectives, they’d assumed they’d be sitting with them while the cops talked about their jobs. Instead, Grosso and Egan took the two actors out on the street with them, executing searches and rousts, experiencing the day-in/day-out of being a narcotics detective in Harlem.

Grosso talks about one of the movie’s most famous set-pieces, a scene where Doyle storms into a bar that’s a hangout for low-level dope peddlers. “Eddie must’ve done the thing in the bar a dozen times in those three weeks (we were with the actors). I’d seen him do it a thousand times before.” According to Grosso, during the first week, the actors would stand outside the bar while he and Egan went inside; the second week, the actors would be inside with the detectives while they rousted the bar. “The third week, we waited outside while Gene and Roy did it!”

“It’s like a set of railroad tracks,” says Grosso. “One rail is the experience of the cops; the other rail is the perception of civilians.” When the rails are too far apart or too close, explains Grosso, the train can’t run. “In French Connection, the balance was just right.”

While Grosso credits much of the movie’s success to Friedkin (“Billy’s a genius,” he says unabashedly), he is also aware of the collaborative network of which Friedkin was a part. The commitment to

Grosso particularly notes the contributions of producer Phil D’Antoni. D’Antoni had started in radio and television producing specials like An Evening with Elizabeth Taylor; hardly the fare to indicate his qualities as a producer of the hardest of the hard-boiled classic cop thrillers. But in 1968, D’Antoni had delivered the lean, terse Bullitt, a movie which had successfully combined Hollywood entertainment with a sense of authenticity. Bullitt star Steve McQueen had gone as far as to do ‘ride-alongs’ in patrol cars to help ground his portrayal of a sharp, veteran San Francisco PD detective. Having feared a typical Hollywood shoot-‘em-up, San Francisco city officials had been quite pleased with the finished picture. D’Antoni hoped to repeat the accomplishment with The French Connection.

However, where director Peter Yates and cinematographer William Fraker had played to Bullitt’s sense of toughness with a sun-burnished hardness befitting the West Coast setting, D’Antoni wanted a different look for the New York-set The French Connection. He’d seen a few TV documentaries made by Friedkin, thought that was the look the film needed, and though Friedkin had done little feature work, decided, “He felt right.” Helping Friedkin get the sooty, winter-in-New York drabness was another relative newcomer to features, cinematographer Owen Roizman, who, at the time, had only one previous feature credit (Roizman would be nominated for an Oscar for his work on Connection).

“Billy had a partner in D’Antoni,” explains Grosso. Though producer and director would tussle over competing visions throughout the production (“Fox threatened to fire Billy many times on French Connection,” reports Grosso) it was their collaboration which brought together the elements which made the film a classic.

For example, the famed car chase was not a part of the true story, nor was it initially part of Tidyman’s adaptation. D’Antoni had explicitly stated he wanted a chase to outdo the one in Bullitt, but Friedkin kept putting off dealing with the sequence. “We did have a chase,” says Grosso, “but it was completely different.” According to Grosso, there was to be a scene where one of the drug suspects boards a subway shuttle and loses Hackman and Scheider. The pair then run back up to the street to race across town and head off the shuttle. Grosso says it was D’Antoni’s idea to move the entire chase above ground.

In The French Connection 30th Anniversary Special, Friedkin explains how the sequence was actually developed to be shoehorned into the narrative. In a long conversation with D’Antoni, director and producer pieced the sequence together in reverse order. First, they needed the bad guy on the train, which meant Hackman would be in the car, which meant he would have to commandeer the car, etc.

Grosso was not always satisfied with the creative decisions which were made. “I asked Billy not to have Hackman shoot that guy in the back,” he says, referring to the climax of the chase when an exhausted Hackman calls to the Frenchman (Marcel Bozzuffi) who’s tried to kill him, then shoots him when the killer turns to run. “I was so pissed off at him for doing that!” But even Grosso admits that when he saw the finished film, “it worked. The audience cheered like hell! He was right.”

Grosso was not always satisfied with the creative decisions which were made. “I asked Billy not to have Hackman shoot that guy in the back,” he says, referring to the climax of the chase when an exhausted Hackman calls to the Frenchman (Marcel Bozzuffi) who’s tried to kill him, then shoots him when the killer turns to run. “I was so pissed off at him for doing that!” But even Grosso admits that when he saw the finished film, “it worked. The audience cheered like hell! He was right.”

As with Bullitt, the authenticity of so much of The French Connection made even such Hollywood prerequisites as the car chase and shootings appear as credible as anything else in the film. Made for $1.8 million (a modest sum even then), The French Connection, released in 1971, was both a critical and commercial hit, nominated for eight Oscars, winning five, and earning nearly $52 million at the US box office (“That picture bailed out Fox,” Grosso says).

Grosso would go on to act as a consultant and technical advisor (and occasional bit player) on a number of other movies, including The Godfather (1972), Report to the Commissioner (1975), Cruising (1980), and The Brinks Job (1978) (these last two also directed by Friedkin), as well as write the story for The Seven-Ups (1973) which Phil D’Antoni would direct. Grosso also advised on several TV series including Kojak, The Rockford Files, and Baretta. After retiring from the NYPD, it almost seemed a natural step for Grosso to begin his own production company, partnering with TV producer Larry Jacobson.

Looking back over several generations of movie cops, Grosso describes the evolutionary line: “We went from a time when the cops were the bad guys to, ‘Just the facts, Ma’am,’ then the cops were the good guys but real people, and now the cops are superheroes.” These days, he says, “Each movie tries to outdo the others.”

While he rues the change, it doesn’t surprise him. The movies are “…a copycat world. If you have a car chase where the car goes sixty miles an hour, then in the next movie it’s going to go eighty, then the next one it goes ninety and everybody’s got a car chase in their movie…Now, it’s all everything blowing up, cars going over bridges…outstunting each other.” He shakes his head. “Where would Frank Capra fit into Hollywood today?”

Part of it, he concedes, is a reflection of the “excessive world we live in.” He points out that, “You’ve got bad guys today who can take out the World Trade Center. What do the good guys have to do to fight that? So, you see a lot of heavy technology, a lot of heavy firepower. When was the last time you saw a detective in a movie use a magnifying glass?”

But just as much behind the change is a Hollywood mindset targeting young audiences. “They’re not even worrying about whether or not old viewers are going to come any more,” he sighs. “They’re addressing movies to younger and younger audiences.” The growing action quotient in the latest generation of thrillers moved Grosso to once ask Bruce Willis, “If it keeps on like this, how many people are you gonna kill in the next movie?”

It is not so much the violence Grosso takes issue with as how it is trivialized. “This is a violent country we live in, a violent world. My only problem with violence is you don’t show the results of violence.” He mentions fist fights and brawls where eyes don’t get blackened and teeth remain firmly fixed in jaws. “The first time you shoot a guy, you’re not right for a long time after that. It disturbed me for months. You don’t feel or see that in the movies.”

He felt his series Night Heat was an attempt to get back to a “Just the facts, Ma’am” kind of cop storytelling. “TV still keeps it life-size,” he judges, “even if a lot of it is a simplistic, problem- of-the-week kind of thing.” But even TV cops have gone down a path which doesn’t exactly enamor Grosso. “Kojack looked like they kept him in a box until the next episode. You didn’t even know he had a penis. Then you look at NYPD Blue. That’s exactly what it was: a blue version of the old N.Y.P.D. (a 1960s series from producer David Susskind) that was less about crime than everybody’s personal problems.”

of-the-week kind of thing.” But even TV cops have gone down a path which doesn’t exactly enamor Grosso. “Kojack looked like they kept him in a box until the next episode. You didn’t even know he had a penis. Then you look at NYPD Blue. That’s exactly what it was: a blue version of the old N.Y.P.D. (a 1960s series from producer David Susskind) that was less about crime than everybody’s personal problems.”

He is pessimistic about the possibility of a swing back to the more realistic cop thrillers of the 1960s and 1970s. “I know people who’re waiting for a change, but I don’t think it’s gonna happen…As long as young audiences like it, it’ll stay the way it is. Is it interesting? It’s all interesting. I went to these pictures when they first started coming out. But it’s all the same thing now…If I had the money, I would make them the way they used to.” He reflects on the decision-making behind The French Connection, from Fox’s acquiring the property on through the production: no focus groups, no audience research, no talk of demographics. “In those days, they were still making decisions on guts.

“I find it sad that you and I have a conversation where I say, ‘Where’s the place for a Capra?’ and you say maybe we couldn’t even get The French Connection made today.” He shrugs. “Maybe you could make it today. But Popeye’d have to be way better looking. And they’d give him a girlfriend. And there’d have to be more action. Lots more action.

“Right now, everybody’s looking for something different. They should be more concerned about just doing it well.” He considers something said to him about the modern-day movie-making process: the input from marketers as well as development people, the parade of rewrite men, the demands of stars pulling a project one way while a director pulls another. “Somebody said to me, is the problem that there’s too many cooks spoiling the broth?” He shakes his head. “The problem is, there’s too many people in the kitchen who can’t cook.”