Directed by Nenad Cicin-Sain

Written by Nenad Cicin-Sain and Richard N. Gladstein

USA, 2013

A passionate starving artist is at the center of The Time Being, an overly portentous new drama that doesn’t see such a central figure as being too stereotypical. No, this is a movie about how Art is Serious, so serious, in fact, that focusing entirely on one’s work trumps trivial matters like work, family, friends, and more. Though the movie is packed with pretty images, thanks entirely to the skill and craft of its fairly overqualified cinematographer, The Time Being is a mostly limp portrait of the artist as inwardly selfish and ambitious.

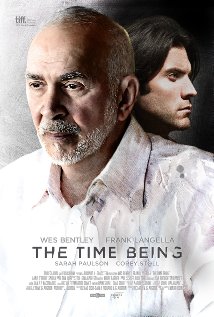

Wes Bentley plays Daniel, so dedicated to his art—he paints based on photographs he takes of the world at large—that one could imagine this guy as being Ricky Fitts from American Beauty all grown up; this man could easily have been entranced by a floating plastic bag when he was a teenager. Daniel has a beautiful, long-suffering wife (Ahna O’Reilly) and young son, but all he truly cares about, or all he thinks he cares about, is his not-particularly-popular art. One day, he’s called upon by a reclusive millionaire—and at a certain age, don’t they all become reclusive?—who instructs Daniel, in no uncertain terms, to start filming what seem to be basic concepts: a sunrise, a sunset, an exhibit in an art gallery. Soon, Daniel realizes that this old man (Frank Langella) may have an ulterior motive or two at heart.

Sadly, the plot summary promises a more enticing and potentially thrilling film than The Time Being actually is. It’s true that Werner, Langella’s character, has a few secrets in his life, and that his edicts are more loaded than Daniel initially perceives. But there aren’t really any surprises to be had in this film, co-written and directed by Nenad Cicin-Sain (the other screenwriter, Richard N. Gladstein, produced). It’s hard to tell if Daniel is meant to sleepwalk through his life, or if Bentley is simply doing so through his performance. All of the characters, really, are prone to declarations about how they care about art, how they are passionate about life, how family is important and should not be ignored, etc. The more declarative statements we hear, however, the less we know the people on screen. They are more ciphers than characters.

The same goes for Langella, who’s the best performer in the film, as one might expect. His work is not terribly surprising, of course; he’s gruff most of the time, but shows a streak of tenderness in one third-act sequence. He and Bentley are on screen more than anyone else in the small ensemble, yet it’s hard to get a good read on the relationship Werner and Daniel are supposed to have. One might presume that an initially frosty business partnership will melt into something closer to respect or faux-paternal love, but nothing like that occurs between the duo. Does Daniel learn anything from Werner through their interactions, or vice versa? The movie ends as answer-free as it starts. Considering how fond the script is of those declarative statements, it’s a bit baffling that The Time Being remains almost maddeningly vague in terms of character growth or development.

Also, it’s kind of a shame that this movie teases the audience with actors like Corey Stoll and Sarah Paulson in smaller, pivotal roles that don’t amount to more than three scenes each. Stoll, so vibrant and arresting in films like Midnight in Paris and TV shows like House of Cards, deserves to play the lead role here; Daniel would still be something of a wet blanket, but an actor with more depth and range would inform and enhance the stale lead. Paulson’s performance and role is the only injection of coherent, believable reality in a movie drunk on the concept of art being so powerful and overriding that all other aspects of life fail to measure up. It’s interesting that she and O’Reilly play the most logical, intelligent characters in The Time Being, which seems to revere its daring men more than the shrewd, tolerant women who suffer their selfishness. Interesting, but likely not intentional.

The Time Being wants to represent a statement on the power of art, and visually, it does. Cinematographer Mihai Malaimare, Jr., fresh off his exceptional work in last year’s best film, The Master, offers an array of beautiful images on his cinematic canvas. If nothing else, this film looks the part, a visual testament to the moving or still image as true, titanic art. Sadly, as striking as the film looks, whenever Daniel or Werner take the stage—which is extremely often—it falls flat. Art is an important part of life, and those who strive and struggle to create art deserve some plaudits, but The Time Being is too unswervingly convinced that art is all-powerful to offer some healthy context or perspective.

— Josh Spiegel