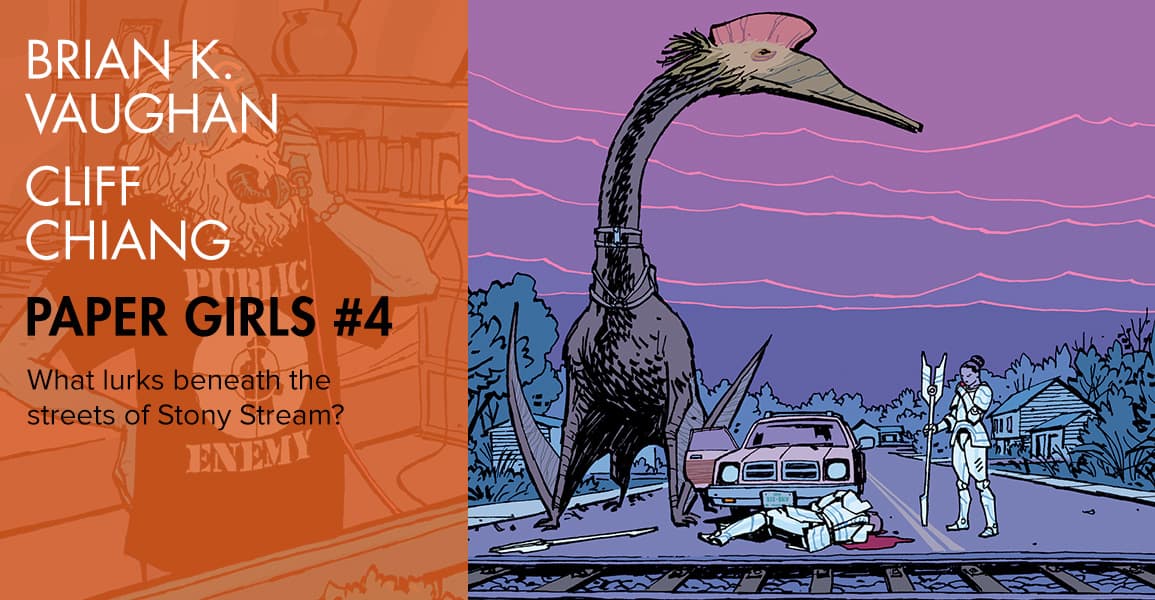

Written by Brian K. Vaughan

Art and Cover by Cliff Chiang

Colors by Matt Wilson

Letters and Design by Jared K. Fletcher

Published by Image Comics on January 6, 2016

Paper Girls #4 continues to be mysterious, genre-mixed, and sometimes surprisingly dramatic in its weirdness; beautifully and evocatively illustrated and colored; and marvelously fun to try to decode the references to figure out. I remain completely enamored with it.

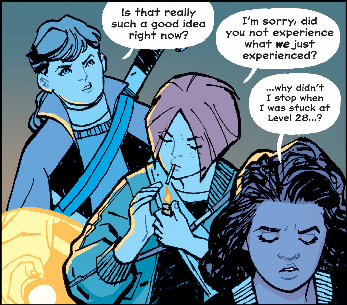

The routine of suburban middle-class life is an existential hell according to Paper Girls #4.  It’s a repetitive game falsely pushing us to the next level, challenging us day to day, year to year, to tackle greater responsibilities, but not offering much true novelty. The looping soundtrack lulls us into a dream-like state of passivity. Life does to us rather than us doing life. We strive for the final boss in one prolonged sitting, no extra lives, our arrival meaning the realization that winning or losing both lead to the same black screen. “Why didn’t I stop when I got stuck on level 28?” Aye, there’s the rub.

It’s a repetitive game falsely pushing us to the next level, challenging us day to day, year to year, to tackle greater responsibilities, but not offering much true novelty. The looping soundtrack lulls us into a dream-like state of passivity. Life does to us rather than us doing life. We strive for the final boss in one prolonged sitting, no extra lives, our arrival meaning the realization that winning or losing both lead to the same black screen. “Why didn’t I stop when I got stuck on level 28?” Aye, there’s the rub.

Contrasting the video game-like Sisyphean struggle of daily life’s routine, the paladins of the future, morally cleansing Stony Stream on the backs of dinosaurs, have a mission. They are willing to make drastic, life or death decisions in the name of whatever god or ideology they follow. Thus, there seems to be a conflict between existential freedom and moral tyranny. Besides the deadly “wash” being perpetrated on Stony Stream in the style of some apocalypse ala Revelations, Erin’s Catholic dream iconography has been threatening and horrific.

Morality comes up again with the reveal that the mutant teenager killed by Alister was Heck’s boyfriend. Mac, who had previously used the word faggot casually to disparage another character, produces an immature and condemnatory, “Eww.” She later calls Heck and Naldo perverts. KJ calls her out on her homophobia, saying Mac sounds like her racist uncle. Heck dismisses it, saying to KJ, “Don’t worry about it. You guys are from an effed-up time.” I appreciate the direct address of the era’s (or at least Mac’s) prejudice.

As far as plot goes, this issue introduces one of the paladins’ leaders, an old-timer, literally, in a Public Enemy t-shirt and a guru-like third-eye forehead marking. He has an apple eye phone (a play on Apple iPhone and connection to the anachronistic Apple Nano Erin finds in the first issue). The eye opens when the call comes in, an incredibly surreal set of panels which call back to Erin’s first dream, reconnecting her rotting apple of innocence once again with telecommunications. He uses the Brit slang bloody hell and talks as we do, not like the paladins whose speech seems cobbled together from various eras of time, from Chaucer to the future version of texting slang. In addition, his tee suggests he identifies with Erin’s era (and anti-authoritarianism), either because he originates from it or he’s a big fan. This could be a clue as to why the paladins are cleansing this time in particular.

As far as plot goes, this issue introduces one of the paladins’ leaders, an old-timer, literally, in a Public Enemy t-shirt and a guru-like third-eye forehead marking. He has an apple eye phone (a play on Apple iPhone and connection to the anachronistic Apple Nano Erin finds in the first issue). The eye opens when the call comes in, an incredibly surreal set of panels which call back to Erin’s first dream, reconnecting her rotting apple of innocence once again with telecommunications. He uses the Brit slang bloody hell and talks as we do, not like the paladins whose speech seems cobbled together from various eras of time, from Chaucer to the future version of texting slang. In addition, his tee suggests he identifies with Erin’s era (and anti-authoritarianism), either because he originates from it or he’s a big fan. This could be a clue as to why the paladins are cleansing this time in particular.

A female paladin named Cardinal calls in to report that Alister has been “unmoored.” Those responsible have “ghosted” along with some stragglers. The boss man, addressed as Grand Father, orders an Editrix be sent.

Cliff Chiang and Matt Wilson ink and color Tiffany’s near-death experience with evocative detail. The passing of months shows in clothing and hair, house decorations, and holiday-connected color changes. Tiffany’s emotional response to the game is likewise effective in relating the narrative of her game-focused life without any text except the game level. She begins fully engaged in the game, and remains so through the many months it takes her to beat the game. Her joy at the victory is short-lived, replaced in the next page’s panel with a set, affectless focus. She continues to play out of routine, maybe a desire to repeat the happiness of winning. Ultimately, she’s not engaged enough in her own life to adopt a new goal. It is easier to avoid choice and change.

Vaughan’s choice of the game Arkanoid has some interesting possible parallels with the sci-fi elements of the story. The opening text of the NES version establishes a narrative around the brick-breaking game: “THE TIME AND ERA OF THIS STORY IS UNKNOWN. AFTER THE MOTHERSHIP “ARKANOID” WAS DESTROYED, A SPACECRAFT “VAUS” SCRAMBLED AWAY FROM IT. BUT ONLY TO BE TRAPPED IN SPACE WARPED BY SOMEONE……..” The end of the game resolves this with: “DIMENSION-CONTROLLING FORT “DOH” HAS NOW BEEN DEMOLISHED, AND TIME STARTED FLOWING REVERSELY. “VAUS” MANAGED TO ESCAPE FROM THE DISTORTED SPACE. BUT THE REAL VOYAGE OF “ARKANOID” IN THE GALAXY HAS ONLY STARTED……”

It’s like they’re talking about me!

So in both Arkanoid and Paper Girls, the question of time and era is muddled. Clearly the mutant teens the paladins, their dinos, and the new guru are from different eras. Heck references Calamity, which reset the marking of years, which may or may not be connected to the dreaded C-day Grand Father doesn’t want to repeat. The Cronenbergian Tardis (which now calls to mind Robert Mapplethorpe’s contemporaneous photography thanks to Heck sticking his arm in its entry sphincter up to his elbow) seems sized to be an escape pod, an analog perhaps to Vaus in Arkanoid. They certainly seem like they are scrambling away from something bigger and more powerful, and the paladins could have a mothership. They also seem trapped in 1988, scavenging tech parts from various communication devices to fix whatever problem keeps them from escape. Perhaps we’ve even already met Paper Girls’ DOH, if the Public Enemy t-shirt is indication that Grand Father might have warped space-time to show up in 1988 Ohio.

On the motif of clowns, who have shown up at least thrice now: 1) one of the teen hoodlums in issue #1 was a dressed as a clown for Halloween, 2) one of the yards had that clown-head sprinkler by Wham-O, 3) in this issue, Erin references the sixth bucket of The Bozo Show’s final game. Bozo the Clown was the star of the show aired on WGN out of Chicago during the late 80’s. Each of these clown references is a deliberate choice in the writing and art, so what is it pointing to? My theory is that it is meant to evoke a fourth clown in the form of Stephen King’s It which was published in ’86 and incredibly popular by ’88. The title being It hunts seven children as prey by disguising itself as their worst fears, usually a clown. Paper Girls‘ seven children: Erin, Mac, Tiff, KJ, Heck, Naldo, and the deceased Jude. It’s structure alternates between two time periods; I wonder if we’ll see the destination of the pod trying to save Erin and if it will be a different time. The themes of King’s novel end up being about the power of childhood memory, childhood trauma, and the ugliness lying beneath the facade of small-town values and life. Already the comic has dealt with the power of memory through Mac’s stepmom and with trauma through the shooting of Erin. The corruption of small-town values has been hinted at. For instance, Erin’s family has been actively trying to win over her xenophobic neighbors.

On the motif of clowns, who have shown up at least thrice now: 1) one of the teen hoodlums in issue #1 was a dressed as a clown for Halloween, 2) one of the yards had that clown-head sprinkler by Wham-O, 3) in this issue, Erin references the sixth bucket of The Bozo Show’s final game. Bozo the Clown was the star of the show aired on WGN out of Chicago during the late 80’s. Each of these clown references is a deliberate choice in the writing and art, so what is it pointing to? My theory is that it is meant to evoke a fourth clown in the form of Stephen King’s It which was published in ’86 and incredibly popular by ’88. The title being It hunts seven children as prey by disguising itself as their worst fears, usually a clown. Paper Girls‘ seven children: Erin, Mac, Tiff, KJ, Heck, Naldo, and the deceased Jude. It’s structure alternates between two time periods; I wonder if we’ll see the destination of the pod trying to save Erin and if it will be a different time. The themes of King’s novel end up being about the power of childhood memory, childhood trauma, and the ugliness lying beneath the facade of small-town values and life. Already the comic has dealt with the power of memory through Mac’s stepmom and with trauma through the shooting of Erin. The corruption of small-town values has been hinted at. For instance, Erin’s family has been actively trying to win over her xenophobic neighbors.

These patterned details act as a kind of cypher to decode the mysterious workings of the plot machinations. Or maybe they’re fun red herrings. Only time will tell. I, for one, anxiously await the future.

If you’d like to check out the expanded decoder for the chrononaut’s language (brought to you by the letter X) and panel translations of Heck and Naldo’s dialogue, click on through to The Dinglehopper.

Three new tracks added to my Paper Girls inspired Spotify playlist. “Time After Time” by Cyndi Lauper (1983), “Don’t Believe the Hype” by Public Enemy (1988), and “Arkanoid” by Martin Galway.