Written by John Jacoby, Samuel Hofffenstein, Eric Taylor

Directed by Arthur Lubin

U.S.A., 1943

It comes as a surprise to no one when stating that Hollywood is not averse to remaking movies. It is an old practice that goes back many decades, all the way back to the earliest days of the studio system. Great stories, apparently, bear retelling with more modern casts and more modern filmmaking techniques. In some cases, it is an issue of actually modernizing the setting, whereas in others instances the studio believes that audiences crave a new version of a familiar classic even though it was a period piece to begin with. Among several early attempts at refurbishing highly regarded motion pictures was 1943’s Phantom of the Opera, released not quite 20 years after the terrifying original and about 15 years after said original was itself the subject of tinkering to satisfy the desire of late 1920s movie goers to see ‘talkies’.

Enter workman director Arthur Lubin (who, by glancing at his filmography, was astonishingly fast at producing movies) and a team of new screenwriters to adapt Gaston Leroux’ venerable French horror-mystery novel. Back to the Paris Opera House we go, this time to follow similar but not quite identical characters. The movie opens with an ostentatious show on display for the admiring patrons. Anatole Garron (Nelson Eddy) is singing his heart out and stealing glances from background singer Christine DuBois (Susanne Foster), much to the ire of leading diva Biancarolli (Jane Farrar). Clearly, a love triangle is causing tension within the musical group. Just below the stage are the musicians, among them violinist Erique Claudin (Claude Rains), who greatly admirers Christine too, although the exact nature of his affections is not made clear. Unfortunately for him, the conductor has detected his diminishing form and, shortly after that evening’s performance, dismisses Erique in as dignifying a manner as possible after years of service. Things go from bad to worse for Erique when he visits a music publishing house to receive feedback after their evaluation of his concerto. When it becomes apparent that they plan on using his music without paying the necessary royalties, an already distraught Erique enters a fit and murders its manager, but not before a fearful assistant tosses a conveniently situated bowl of acidic liquid onto his face. Erique fless the premise, heavily scarred, but concocts a new plan, one that directly relates to his obsession with Christine back at the Opera House….

The above synopsis is significantly more plot heavy than that for the 1925 Rupert Julian directed effort. What’s more, it does not take into consideration any of the action once the Phantom goes about his ghastly ways in order to seduce the ambitious Christine. That would have required another few lines to an already long description of what happens in second major motion picture version of the classic love story. The reason is very simply: the 1943 Phantom is very plot-heavy. It is so plot heavy that, oddly enough, it comes across as a modern film. Too many movies released these days, among them remakes and reboots, are lambasted for their convoluted scripts that endlessly add plot as though it was as important if not more so than story. Interestingly enough, this practice, especially when dealing with remakes, goes back to the golden age of Hollywood if this film is any indication.

If plot is used well, then screenwriters and directors can tack on as much as they see fit. However, in a great many instances, that is not the case. In the current example, the issue of a plot-heavy movie dragging the end product down is obvious from the first 20 or 30 minutes. It takes in incredible amount of time before Erique Claudin transforms into the titular antagonist. The film is deadest on making him more deserving of the viewer’s empathy than his 1925 counterpart ever was. While this is not a bad idea in theory, in practice it hurts the film in two important respects. First and foremost, the movie’s pacing is quite sluggish in the first act. It almost comes a surprise when the Phantom is finally born because the viewer started to get the impression that they were watching a totally unrelated film. Second, this storytelling choice removes a lot of the mystery surrounding one of the great monsters of early 20th century cinema. Part of the fun of an interpretation of Phantom is not knowing just who or what the creature is, at least until later in the picture. That dramatically effective angle is tossed into the garbage bin for this 1943 remake.

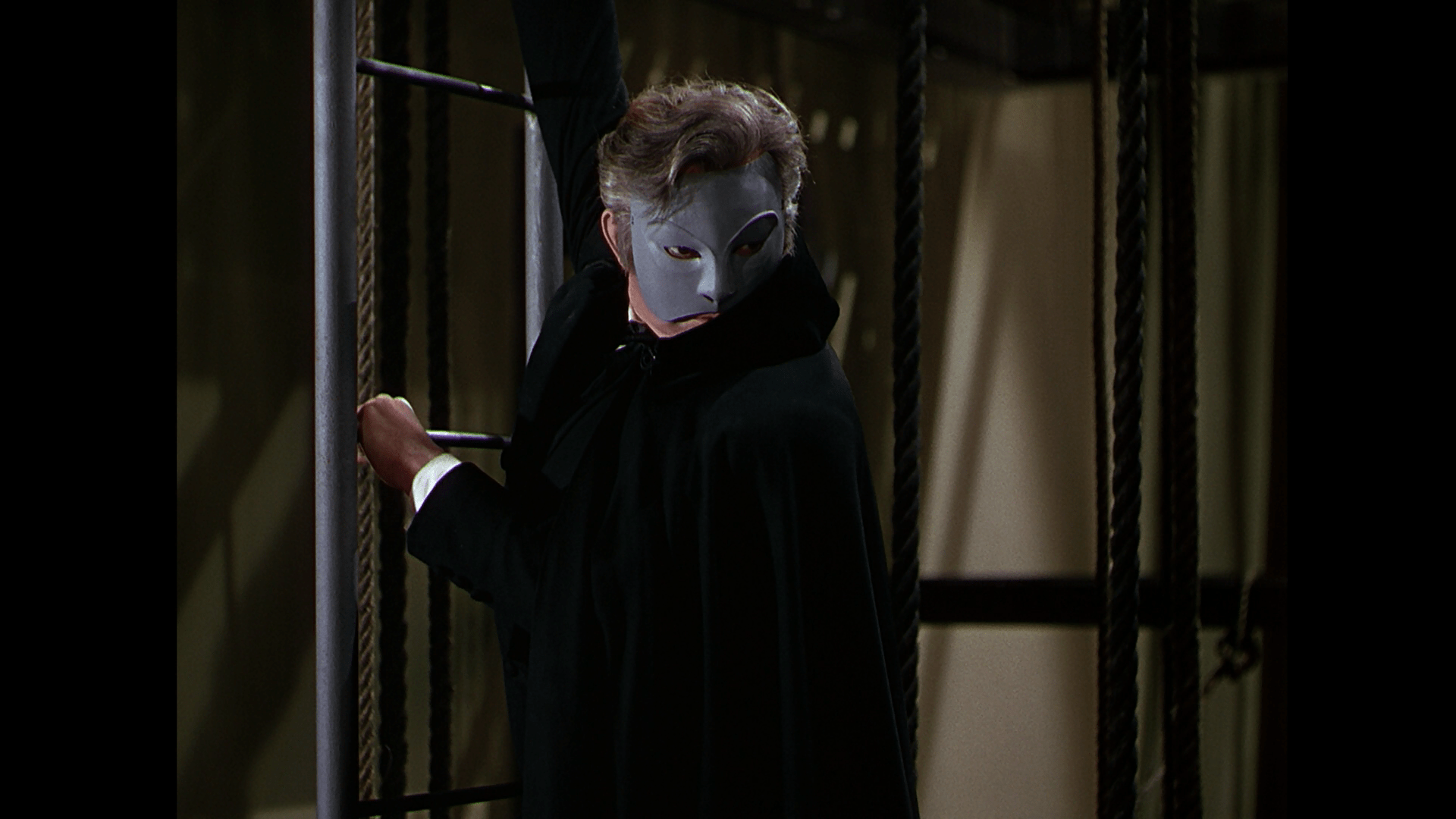

A third problem, albeit a slightly more indirect one, is how the movie goes from placing Erique as the obvious central figure for the film’s first half, painstakingly showing his story and how tragic a figure he is, only to save him for cameo appearances in the second half. Not revealing too much of the Phantom is a smart move, but the problem is that the screenwriters and director Arthur Lubin, as previously argued, have killed the mystery surrounding him, so having him become an infrequently seen, shadowy figure for the second half feels misplaced after having invested so much time in creating the character in the first place.

Not helping matters is the decent but unspectacular performance from leading lady Susanne Foster as the damsel in distress and apple of the Phantom’s eye, Christine DuBois. As the center of everyone’s attention, from the Phantom all the way to police inspector Raoul Dubert (Edgar Barrier), it is unquestionably important that the actress portraying the part be capable of fluttering hearts and win viewers over with her charm. Foster is a capable Christine, but nothing to write home about, unable to create a truly special heroine worthy of so many characters’ admiration, jealousy and desire.

Most critically, the film simply fails as a horror film. In fact, describing it as a horror film is questionable. In all honesty, it works more effectively as a romantic musical. A handful of times the drama makes a full stop so that Lubin can relish the operatic skills on full display by his cast and set design team. Opera lovers may rejoice, and good for them. There is nothing wrong in principle with featuring some opera in a telling of Phantom of the Opera (it’s in the title, after all), but this iteration puts an incredible amount of time in showcasing bombastic musical numbers. One wonders if the producers were more interested in making a musical rather than a horror film. In a nutshell, this Phantom is not the least bit scary, or even unnerving.

Despite everything that has been argued thus far, Arthur Lubin’s picture is not all bad. In fairness, it does have a few key elements operating in its favour that make it worthy of at least a single viewing experience. The most obvious positive to take away is, understandably, the presence of the legendary Claude Rains. For all the criticisms that can be aimed at the mistake-laden script that clumsily tries to make the Phantom interesting, Claude Rains himself is more than accomplished enough to make him interesting. A lot can be wrong with a movie, but if it is anchored onto Rains’ screen presence, it will still be watchable. He sells the tragedy of his role far more convincingly than the script.

On the topic of good acting, it would be remiss to omit mention of Nelson Eddy and Edgar Barrier, as baritone Anatole Garron and policeman Raoul Dubert respectively, two men that vie for Christine’s affections. Both are genuine gentlemen, unwilling to debase themselves to classless bickering, even for the sake of a beautiful woman. As such, their rivalry carries an aura of sophistication and class. Each wants Christine for his own, but each also respects his rival’s social status and professional accomplishments. It is actually a rather light-hearted affair, supplying the film with its few comedic beats. Admittedly, this is another element that distances the movie from its horror roots, but it is hard to deny their charisma. At the end of the day, fun is still fun.

Decorated with splendid set and costume designs, Phantom of the Opera is also a feast for the eyes. Even so, and despite some really strong performances, this interpretation is disappointingly uneven in how it shapes its story and balances its tone. Despite important technological advancements in filmmaking, this 1943 Phantom underperforms in the more critical categories, like telling a darn good story, which is a shame when dealing with one of the great horror stories ever told.

-Edgar Chaput