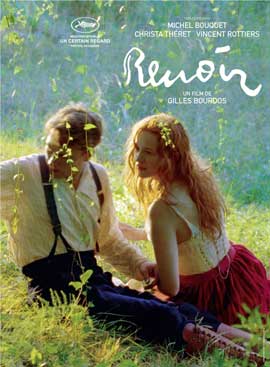

Directed by Gilles Bourdos

Written by Jérome Tonnerre, Michel Spinosa, and Gilles Bourdos

France, 2012

Sometimes, it is more fascinating to watch the struggle a film has in trying to balance dual aims than it is to watch the movie itself. Case in point: Renoir, a feature showcase at this year’s Phoenix Film Festival. In essence, Renoir tells us of how an alluring young woman came into the lives of the impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir and his son Jean, and how she changed all of their lives. This is a film at its best when it focuses on the natural sights and sounds surrounding this trio on the Cote D’Azur. Whenever the script is required to perform any heavy lifting, you can almost see the strain behind the camera, as if the filmmakers aren’t sure how much we need to know to connect the dots, to fill in the blanks of the various relationships at Renoir’s estate.

Michel Bouquet plays the elder Renoir, in the autumnal years of his life. He spends his days painting whatever pleases him most, as he flatly mentions midway through the film that he has no use anymore for “poverty, despair, or death.” Into his life enters Andrée, a pretty, strident redhead who says she was referred for a job as Renoir’s new model by his wife; the only wrinkle is that Renoir’s wife is (and has been for some time) dead. Before we can wonder too much about exactly how Andrée found the job–with the exception of one late sequence, pretty much all of this movie is set at his expansive abode–Renoir’s 21-year old son Jean returns from World War I on sick leave so his wounded leg can heal. Jean and Andrée begin a tentative romance as the young man begins to be inspired by the moving picture and what he could potentially contribute to the medium, while tending to his infirm, ever-so-slightly deformed father.

Gilles Bourdos, as director, is clearly dedicated to making sure Renoir is as artful a film as the subject himself was. There are plenty of standout images here that could serve as their own paintings, whether it be an extreme close-up of a paintbrush being dipped in a glass of water, the residue of color slowly rippling outward like a lava lamp; or extended tracking shots of the lush treetops covering an arthritic old man as he paints nude women luxuriating on a chaise lounge. These various tableaux are quite striking, as is the lilting, subtly propulsive score by Alexandre Desplat. Visually and aurally, Renoir is often a sensory delight. And then, unfortunately, the characters open their mouths and talk.

In the early going, the dialogue isn’t so distracting or bothersome if only because we imagine the story, even if it meanders, will build upon what we learn. When we see Renoir interact with a spectral version of his wife, confirming that she nudged Andrée to the modeling job, we may assume this will be a frequent recurrence, but alas, the potential subplot is dropped almost instantly. We may wonder if this movie will offer more direct hints to Jean Renoir’s future as one of the most respected and honored directors in all of cinema, the man who gave us Grand Illusion and The Rules of the Game. What inspired him? What experiences of his from the war may have led to Grand Illusion? Outside of a few throwaway lines–such as one character dismissing cinema as being something that will never succeed in France, a bon mot perhaps a bit too clever for its own good–little is explored beyond the surface of Jean’s life.

Surface pleasures is all we have in Renoir, a film that firmly adheres to the statement its title character makes when saying that a painting’s meaning can’t be explained, only felt. And it’s not as if film cannot succeed as poetry more than as more direct prose. Renoir stumbles because it wants to be both, and can’t quite balance its urge to feel as powerfully as Renoir himself felt while also telling us how the strong, passionate, and feisty Andrée enticed Renoir to have passion for the living while also becoming ensconced with Jean. Especially since these characters are so cloistered–for at least the first hour, we only meet those who live on the estate, no one from the outside world–we learn too little of their pasts and presents. It is here that Renoir feels most muddled, visually exciting but a mess of storytelling.

— Josh Spiegel