It’s both perfectly fitting and a darkly wry punchline that the last word in Stanley Kubrick’s last film is “fuck,” utilized in its most literal definition. The word is spoken, in both direct and slightly imploring fashion, by Alice Harford (Nicole Kidman) to her husband Bill (Tom Cruise) at the end of the still slightly underappreciated Eyes Wide Shut. Bill’s nocturnal journey into an unfamiliar world of group sex and general deviancy is one of missed opportunities and denied possibilities; he is surrounded by and beckoned into various couplings, and capitalizes on none of them. This weakness of the modern man is a recurrent theme in Kubrick’s filmography, from Paths of Glory to Eyes Wide Shut, released posthumously in the summer of 1999. Kubrick, who died 15 years ago today, was often categorized as a cold and distant filmmaker, always putting his characters at an emotional remove; this qualification is typically meant as a rebuke of his stylistic leanings. The chilly way with which he treated his protagonists, though, is less an obvious example of his auteuristic failings, and more an emblem of how the lead characters in his films are defined by literal or metaphorical impotence.

But something always gets in the way for Harford, just as many male characters in Kubrick films face obstacles to being free of their impotent states of mind. Some of them are simply in denial, granted; General Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove isn’t willing to own up to his self-imposed impotence, as he cheerfully, matter-of-factly informs his colleague-cum-hostage Group Captain Mandrake about how a previous sexual encounter ended abruptly because she wanted to take his “life essence.” Now, Ripper holds his “precious bodily fluids” near and dear, to the point where his paranoid state of mind inspires him to unleash the literal end of the world upon an unknowing, out-of-their-depth humanity, all because he suffered from, at least once, erectile dysfunction. His impotent state is the most aggressive, perhaps, in Kubrick’s filmography, but no less evident than the rest. On the surface, Jack D. Ripper is eerily, unnervingly still while describing his internal manifesto to an increasingly perplexed Mandrake; below it, he’s an immense coward, admitting just before he shoots himself in the head that he wouldn’t hold up under torturous pressure should he be captured by the American soldiers storming their base in the hopes of averting a nuclear apocalypse. The only way Ripper could assert himself was by destroying everyone and everything else around him, all that which made him so lacking in virility, spiritually or literally.

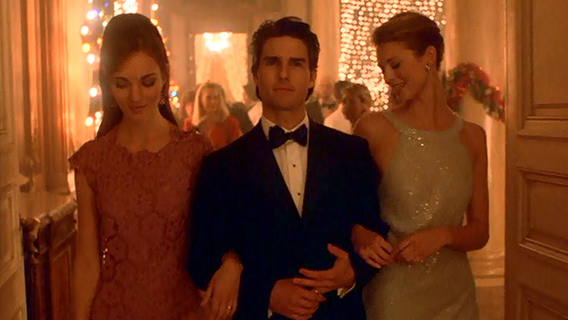

Bill Harford is not as defined by physical impotency as Jack D. Ripper—though she gets merely a handful of lines of dialogue, the Harfords’ young daughter says goodbye to them before they head out to the holiday party early on, the product of at least one successful coupling—but he’s fairly close. He fails as an equal partner in his marriage by not being able to understand that his wife’s sexual fantasies and possibilities are as limitless as he wishes his own to be. Alice’s giddy, pot-fueled description of a passionate dream in which she and a naval officer she’d met on a past vacation had a sweaty, hedonistic tryst is what sets Bill off on his odyssey into the midnight hellscape of New York City and beyond. He’s unable to shake the newfound knowledge that his wife, ever faithful in her waking hours, would be so willing to give herself up to a stranger even in dreams (as she nearly does in her waking moments at that holiday party, nearly swept off her feet by an older Hungarian man who slyly, smoothly bemoans the constricting structure of marital life). Bill, who we only see at his office treating female patients, proves himself wholly unable to grasp and penetrate the female mind, which heightens his impotent state. There are myriad examples of this, as when he’s baffled when his ailing patient’s daughter throws herself at him. Consider also his utter inability to even acknowledge the depths of his mistake of crashing the mansion-set orgy when a mystery woman—though, as we discover by the end, not so mysterious as Bill thought—warns him before she sacrifices herself so he can avoid punishment. Regarding those aforementioned models, he can only verbally flirt with them at the Christmas party, unsure of himself moving further physically before a call from the party’s host saves him from making the choice himself. Finally, he’s nearly too shocked for words to respond to the costume-shop proprietor or his gleeful, lustful underage daughter.

When Bill isn’t being rendered physically impotent—Alice’s laughter before she reveals her dream in a lengthy monologue while stoned is sharp and derisive, each high-pitched trill a slap in Bill’s face—he’s mentally trapped by his own inadequacies. Often in his journey, which is dualistic in nature, he encounters disturbing concepts or characters, and is totally unable to do anything except be a passive observer. He visits the costume shop, first at night to retrieve an appropriate disguise for the orgiastic event ahead, and is shocked to see the owner’s daughter mid-coitus with two Asian men in makeup. The owner is equally shocked, and furious, threatening to call the police on them; Bill watches, the daughter smirking behind him to evade her father’s wrath momentarily. The next morning, Bill returns to hand off his costume after an unsuccessful, cloaked descent into fresh hell, and is shocked by the sight of the once-raging proprietor all but pushing his daughter to sleep with a complete stranger. The two Asian men depart, clearly having convinced the burly costume-shop owner to sell his nubile teenage daughter into willing prostitution.

Then there’s Bill’s reconnection with his old college friend Nick, once a med-school student and now a piano player for hire. One evening, they laugh about Nick’s past jobs and his upcoming blindfolded gig at the mansion, as Bill begs his way into the forbidding atmosphere. The next morning, Bill fears the worst, as Nick has apparently been forcibly removed from his hotel by two thugs, presumably because he gave Bill the password to enter the orgy. (Even here, Bill’s oblivious to the rest of the world finding him attractive, as the insouciant desk clerk played by Alan Cumming oozes saucy flirtation.) Bill demands answers, but has no power to receive any; when he’s confronted by his old friend Victor (Sydney Pollack) about what happened at the orgy, he’s only offered pat excuses about what happened to Nick, and to the woman who saved Bill by taking his place. Maybe Nick just went back home, and maybe Bill’s rescuer just succumbed to her drug addiction, which he witnessed firsthand at that Christmas party. Bill can only wonder.

Bill Harford is the last in a long line of male characters who are forcibly wrested of their power or agency in Kubrick’s filmography; what makes him stand apart from many of these other men is that he doesn’t respond to his impotency with violence or any kind of dramatic upheaval. Humbert Humbert takes out his aggression on the impish man who ostensibly stole his precious Lolita; Jack Torrance unleashes his frustration about fatherhood and being on the wagon upon his family, who are prey for the spectral figures in control of the Overlook Hotel; Private Pyle is molded into the ideal model soldier by his tyrannical drill instructor, and then murders that same instructor because of how far past the brink of sanity he’s been pushed. These men have been rendered inert; in some cases, the lack of power is coupled with a lack of sexual gratification. Humbert, so desirous of Lolita’s nubile charms, is constantly held up from achieving his endgame, in spite of presumably removing all obstacles in his path with relative ease. Jack Torrance sees himself as a failure in so much of his life, and chooses to take it out upon his wife and son, seeing them as the product of his lack of success, and once giving into his desires with an initially gorgeous ghost. Pyle, like the other privates, doesn’t even have a healthy sexual outlet.

Bill Harford is the last in a long line of male characters who are forcibly wrested of their power or agency in Kubrick’s filmography; what makes him stand apart from many of these other men is that he doesn’t respond to his impotency with violence or any kind of dramatic upheaval. Humbert Humbert takes out his aggression on the impish man who ostensibly stole his precious Lolita; Jack Torrance unleashes his frustration about fatherhood and being on the wagon upon his family, who are prey for the spectral figures in control of the Overlook Hotel; Private Pyle is molded into the ideal model soldier by his tyrannical drill instructor, and then murders that same instructor because of how far past the brink of sanity he’s been pushed. These men have been rendered inert; in some cases, the lack of power is coupled with a lack of sexual gratification. Humbert, so desirous of Lolita’s nubile charms, is constantly held up from achieving his endgame, in spite of presumably removing all obstacles in his path with relative ease. Jack Torrance sees himself as a failure in so much of his life, and chooses to take it out upon his wife and son, seeing them as the product of his lack of success, and once giving into his desires with an initially gorgeous ghost. Pyle, like the other privates, doesn’t even have a healthy sexual outlet.

But many of the other men in Kubrick’s films, even when they’re not at a sexual loss, are impotent in other ways. The virtuous Colonel Dax is unable to stop the fruitless and outrageous execution of three of his soldiers, and is barely capable of holding himself together when his superior presumes it was all an act to get a promotion he knows he doesn’t deserve. Barry Lyndon, a cad through and through, is constantly trying to better himself through underhanded means and is met with rejection, leading up to his pathetic passing. Dave Bowman and Frank Poole, the only astronauts not put in hibernation on the Discovery One, are essentially useless, marking time while a cripplingly neurotic computer system is forced to mislead them about the point of their mission; only when Dave is stirred into action, instead of passivity, does he achieve an actual form of evolution, breaking free of his impotency. The rest of Kubrick’s men aren’t so lucky, fighting their powerlessness in ways that only trap them further. There is a saving grace for Bill Harford in the final moments of Eyes Wide Shut; if he and Alice have not returned to their previous idyll, stalking a toy store as Christmas approaches and their daughter wanders around happily, they have at least reached a greater understanding. Bill, throughout Eyes Wide Shut, has to accept how little control he has over his surroundings; now that he and Alice are on the same page about their past desires and about his menacing trip to the countryside, they can go forward in a more mature form of wedded bliss.

— Josh Spiegel