Written by Alan Moore

Art by Jacen Burrows

Colors by Juan Rodriguez

Letters by Kurt Hathaway

Published by Avatar Press, Inc.

We rejoin Alan Moore’s and Jacen Burrows’ Providence to find American life, as our protagonist newspaper man/aspiring author Robert Black specifically notes, in a state of upheaval. Prohibition has just passed. Mobs of angry, out-of-work actors crowd the streets of Manhattan, evoking parallels in people’s minds to the all-too-recent revolutions in Russia. These nuggets of history are not thrown into the story haphazardly, and play out along with some important pieces of commentary from members of the cast. But it’s important to note who’s making these comments, and what demographics are included — or not included — when it comes to the pages illustrating the crowds during the 1919 Actors’ Equity Association strike. If you guessed these pages are dominated by the perspective of white people — specifically white men — you would be correct. However, this centering of the conversation around the feelings of white (men) isn’t done blindly. Rather, it works to orient us to the power structures of the world as we delve further into how these power structures oppress, and who might be to blame.

And make no mistake, Providence #3 does not mince its words when taking certain, shall we say, “genre luminaries” to task. Its message is daring and provocative, making definitive statements about the nature of the more problematic aspects of H. P. Lovecraft’s work. What’s more, this is only issue #3. We still have nine more issues to go, leaving one to wonder whether or not this series has already peaked, or whether we will be drawn to places even more uncomfortable and challenging than the ones we’ve already been to. Whatever the case, Providence #3 is an important work on its own, for both Lovecraft fans and his detractors, and lovers of genre fiction as a whole.

To understand the full breadth of what Moore and Burrows are trying to accomplish here, we should take a look at a couple of the other real-life events going on in 1919 — the year the story is set — some of which are only hinted at in the story itself. In 1919, the Ku Klux Klan was coming off a period of rapid growth and revitalization thanks to the popularity of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation. Adolph Hitler was making waves as a member of the German Worker’s Party — soon to rebrand itself the National Socialist German Worker’s Party under a now-infamous hooked cross symbol designed by Hitler himself. And Howard Phillips Lovecraft was an no-name writer living in Providence, Rhode Island, still several years away from both the commercial publication of his work and the move to New York that many literary historians argue solidified his contempt for persons of non-white, non-Anglo Saxon descent.

This isn’t to draw a direct correlation between the latter and the two former — Lovecraft wasn’t nearly as heinous as all that. By all accounts, his racism and bigotry, while certainly pronounced and extreme beyond the general sentiments of his day, never manifested in action beyond personal utterances and his (at-the-time little-read) writings. Today, despite Lovecraft’s popularity being at an all-time high, discussions of the importance of his work cannot happen without at least some attempt to come to terms with that bigotry. Need I mention that the most important living comic book writer is doing a pastiche of the man’s work, and it’s literally all about that bigotry. But while most Lovecraft critics tends to err on the side that says his work has merit enough beyond its problematic elements that it’s still worth reading and preserving (and yours truly typically falls into that camp), Alan Moore, of all people, seems less willing to let him off the hook than that. Thus, we get what transpires in Providence #3.

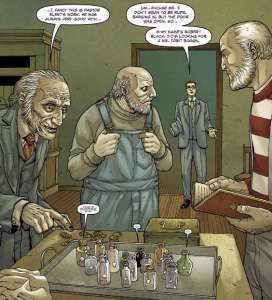

This issue finds Robert Black finally leaving New York in his pursuit of The Book of the Wisdom of the Stars, and ending up in Salem, Massachusetts looking for a man with some knowledge of the matter by the name of Tobit Boggs. This version of Salem features a population of citizens that the art renders with no necks, hunched backs and pasty skins, broad mouths, tiny ears and wide-set eyes. The lettering for these characters even changes to a heftier, ungainly font, indicative of the (presumably) wet, inelegant way their voices are meant to sound. Yes, these are Lovecraft’s “Deep Ones,” and this Salem is obviously a stand-in for Lovecraft’s fictional Innsmouth. But in the pages of this third issue, Moore and Burrows use them to do something completely unexpected.

As the story unfolds, we find that the more “respectable sorts” in Salem don’t take kindly to the presence of the “waterfront folks,” despite the fact that these “waterfront folks” are, so far as the story has told us, doing no harm and just living their lives. These “respectable sorts” deface property, and use a certain symbol in an attempt to intimidate the “waterfront folks” — a symbol that will be very familiar to the reader from a very different context. If what Moore and Burrows are up to doesn’t become clear at this point, it will very soon. They’ve taken the monsters of “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” — as obvious a metaphor for Lovecraft’s anxieties about interracial relationships and the need for racial purity as there can be — and turned them into an outright oppressed minority.

The dream sequence that follows brings into focus the head-spinning web of interconnected symbolism that the creators have been laying out from the beginning. In true Moore fashion, everything has a double meaning, everything serves a dual purpose. The recurring plot point of toxic gases and the fact that the book Black is pursuing is about the wisdom of stars? It’s about more than the ability for toxic substances to mess with the mind and/or kill, and it’s about more than literally seeking the knowledge of the cosmos. This section grows increasingly more disturbing as it introduces imagery associated with historical government-sanctioned persecution — most notably McCarthyism and Nazism. You can probably guess where this is going, but in drawing a line so clearly between Lovecraft’s “Deep Ones” and those who died in Nazi gas chambers or were hounded during the Red Scare and Lavender Scare, Moore is clearly not letting Lovecraft off as easily as other critics (or even I, myself) have in the past.

Moore and Burrows clearly want us to face the horrors wrought by following the underlying messages of Lovecraft’s fiction to their logical conclusion. They essentially expose the most unnerving and disturbing thing about Lovecraft’s horror stories to be the author himself. In his day, Lovecraft was actually a pretty ordinary chap. He was a straight, white, Anglo-Saxon male who made a small career out of trying to scare people with metaphors about how horrible it would be to not be straight, white, Anglo-Saxon, or male anymore. While Lovecraft never actually acted on these beliefs in a physically harmful way, the comic seems to posit that merely having these beliefs was harmful enough.

It may seem extreme, but I see the merit in this. I struggle almost daily with being able to compartmentalize — to look at both people and works of art, and recognize both the good aspects and the bad aspects, and not assume that one negates the other, especially in a broader culture that sometimes seems to prefer “all good” and “all bad.” The easiest thing would just be to just remove Lovecraft from the conversation, but think of the loss that would be. What a suddenly more boring place the genre fiction landscape seems without “The Call of Cthulhu,” At the Mountains of Madness, and the rest. But keeping him there means constantly having to wrestle with the uglier parts, to constantly have to step back and contemplate bigger picture implications whenever a particularly nasty passage about a person of color emerges in your reading. Moore and Burrows, however, seem to think there is a way to relish the work of Lovecraft without this struggle. They know how to keep his work relevant in the twenty-first century, but the only way to do that is to strip him naked and force all of us who would read his work to do a walk of shame with him, to let the weight of his sins really sink in until we all accept and understand exactly what lies at the bottom of it all. It is the only way to purify him.

Providence #3, as odd as it may sound, is a baptism by fire. And it really is something to behold.

Because, don’t get me wrong, outside of harshly deconstructing Lovecraft, Providence #3 is still an eminently readable comic. While much of the story relies on overt references to the Lovecraft canon, picking up on them shouldn’t hinder the uninitiated from enjoying the story. I still enjoyed the debut issue of this series immensely even though I completely missed that the Dr. Alvarez character wasn’t exactly an invention of Moore’s and Burrows’ (the reference was to one of Lovecraft’s more obscure stories, admittedly — that sneaky, clever Alan…). And I only understood the “Red Hook” bits in the second issue to be references after a little helpful Google searching. I suspect the same goes for this issue, even though the “Innsmouth” material jumped at me right off the bat (though there was one bit involving little jars that I did not get).

Robert Black remains a likeable protagonist, and the world he’s delving into continues to become a weirder, richer place, thanks to Jacen Burrows’ impeccable detail, and just how well the decision to portray Lovecraft’s horrors as sympathetic ends up working in the tale’s favor. There are enough little references and in-jokes sprinkled throughout to satisfy Lovecraft fans (for instance, we finally get in-story confirmation that, yes, Robert Black is named for Lovecraft protégé Robert Bloch). Even the supplementary material from Black’s diary ends up working this time — expanding on our understanding of the story and characters rather than just restating it. Moore, as always, is a lyrical prose writer, and the words he gives Black to express his projections and fantasies as part of his unrequited yearning for Tom Malone feels all too real.

This is the best issue of Providence yet. It’s entertaining, it carries some emotional weight, and gives you a full, diverse understanding of the world it’s building. Hopefully this series continues to be as challenging and provocative moving forward. Hopefully the creators have more surprises up their sleeves. If this is the best it gets, well, that’s a little disappointing, but I can live with it. Because this issue here at least lets you know that you can hate a creator and love their creation. It is possible — as long as you’re willing to take it back from them. Art is too important to leave in just anybody’s hands. And that message is good enough.