Written by Alan Moore

Art by Jacen Burrows

Colors by Juan Rodriguez

Letters by Kurt Hathaway

Published by Avatar Press, Inc.

The thing about privilege is that it affords you the ability to ignore the things that make you uncomfortable even when those things are absurdly apparent. This isn’t to say that the privileged are free from merely acknowledging the plight of those without privilege, but it does allow them to more easily overlook the reasons for things being the way they are. In the fourth issue of Providence from writer Alan Moore and artist Jacen Burrows — a horror comic as much about issues of racism, bigotry, and social unrest as it is about the eldritch and the weird, perhaps even more so — the creators manage to weave the issue of privilege in and around some classic genre fiction tropes, giving us an exploration of the topic while at the same time solving one of supernatural horror’s knottiest — and oldest — dilemmas.

So far, Providence is a story told with what you might call the classic “Scully method.” The Scully method is when creators tease out the protagonist’s ignorance of malignant and/or supernatural deeds until the last possible moment in order to maximize suspense. This tactic can often strain credulity as it did in numerous episodes of The X-Files where Gillian Anderson’s skeptical Agent Scully just could not Occam’s razor herself out of the increasingly preposterous “scientific” theories she put forth to explain whatever monster they were facing that week — hence the name.

But Providence finds a way to make the Scully method work logically. So far Robert Black has yet to see the horrible truth behind the things he’s investigating, not because of any kind of willful ignorance (with the exception probably being his demonic encounter in issue #2) but because his privilege prevents him from doing so. Let’s face it: Robert Black is a man with quite a bit of privilege. He’s Jewish, of course, but actively denies it. He’s also queer, but manages to hide it, and his queerness never transgresses the boundaries of gender norms — quite unlike his deceased ex-lover, who had the legal name Jonathan and presented as male in professional life, but was known to Black and others as “Lily,” and is shown in flashbacks in traditionally female dress. To the world, Black is a WASP-y, middle-class, educated, cishet male, and it’s reasonable to assume that life — at least as he’s lived it in New York City, away from his relatives in Milwaukee — has afforded him all the benefits that come with being all those things.

While Black is certainly sympathetic towards those who don’t blend quite so easily — the immigrant communities he encounters in issue #2, for instance, and the beleaguered Salemites in issue #3 — the fact remains that he’s a long way from understanding what it’s truly like to be them, and, given that, he has far more prejudices against them ingrained inside him than he would like to admit.

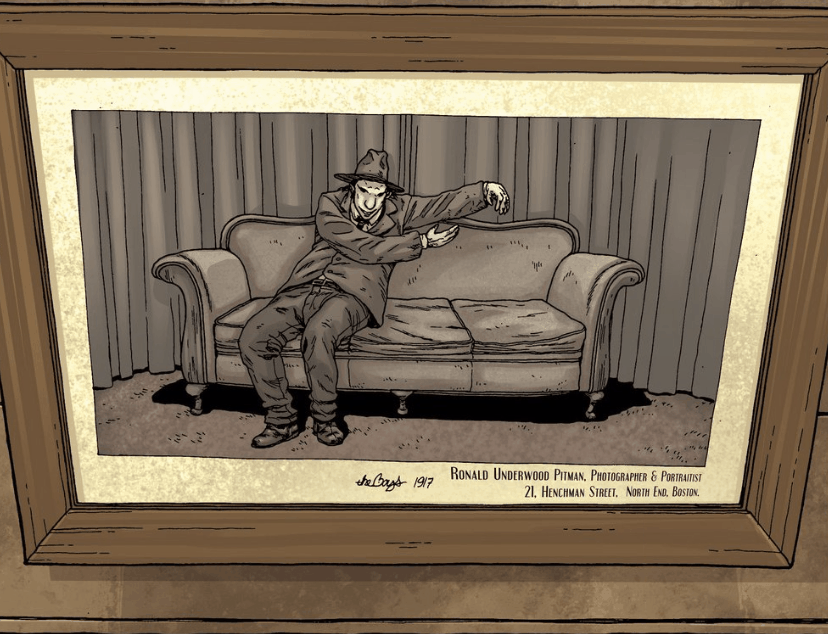

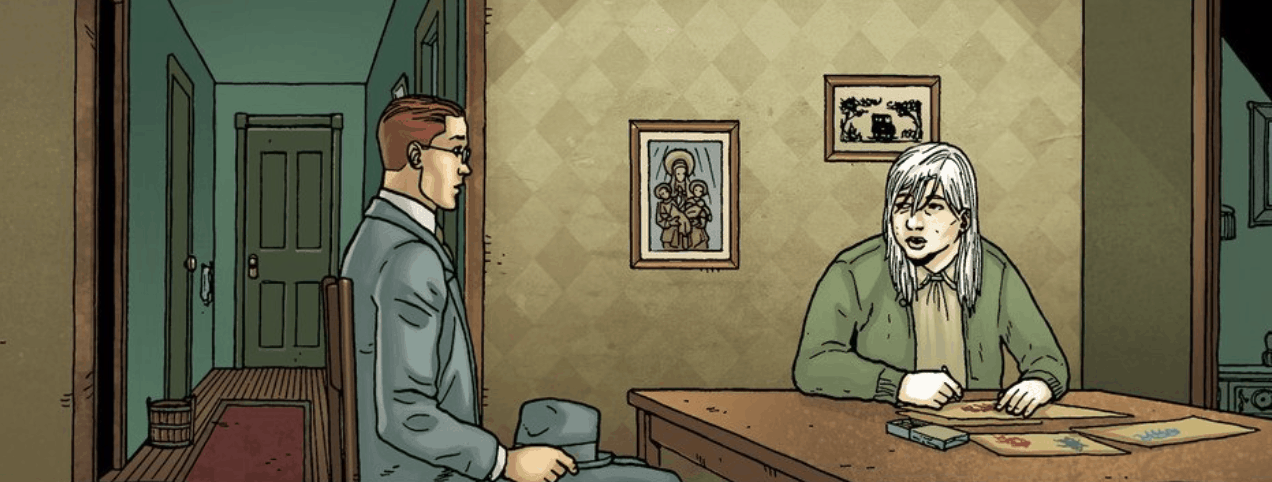

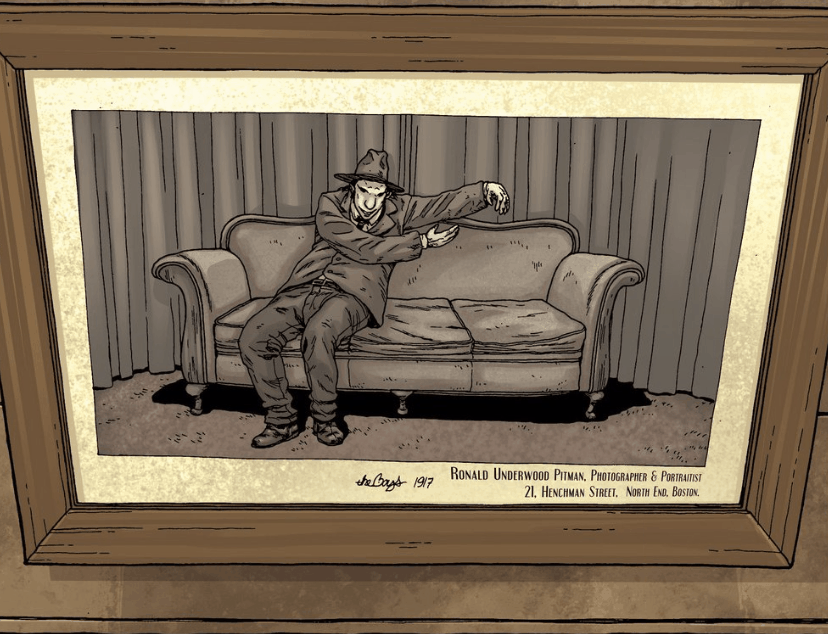

All this leads to how Black manages to bumble his way around the people he encounters in this issue — a family called the Wheatleys — without managing to think that maybe he’s getting into something a little deeper and scarier than he anticipated. Black visits the secluded, run-down old farmhouse inhabited by the Wheatleys as the next stop on his way to finding The Book of the Wisdom of the Stars. The Wheatleys are of course based on the Whateleys, the family at the center of one of H. P. Lovecraft’s most enduring stories The Dunwich Horror, in which the union of a back country family’s daughter with an unknown cosmic entity results in offspring that are… quite horrible, to say the least. Where Robert Black encounters the Wheatleys, however, is in a place quite a bit before the conclusion of Lovecraft’s tale. Black learns a lot about the Wheatleys, but his own bias colors the way he interprets it, and thus he comes away with an impression quite a bit off from reality.

This skewering of Black’s perception comes both through his character development over the past three issues as well as through this issue’s opening scenes where he searches the town of Athol for information on the Whealeys, but only manages to gather nasty opinions from the locals about the “oppressive atmosphere” out among the hill communities, and how it can lead to “declining stock.” Hence why he leaves the situation thinking the Wheatelys are merely a bunch of impoverished, inbred, mentally ill hillbilly bumpkins — albeit with some rather uncommon occult beliefs.

Providence #4 also gives off the clearest picture yet of where this whole saga is heading. It’s clear by now that Providence and Neonomicon have more in common than just a theme and a creative team. And, given the role that Lovecraft’s fiction played within the plot of the previous series, as Black gets closer to The Book of the Wisdom of the Stars and, by extension, the Stella Sapiente cult and their messianic “Redeemer,” perhaps the audience will start to get a firmer grasp of that Redeemer’s identity, and what the role of “Redeemer” entails.

Or perhaps they won’t. This is a series that takes the monsters and horrors of Lovecraft’s fiction and draws parallels between them and society’s outcasts and underprivileged, after all. So far the series has successfully managed to maintain the macabre and otherworldly aspects of Lovecraft’s creations while giving them a dose of sympathy. So far it has managed be quite redemptive of Lovecraft’s mythos, but can it continue to do so while still portraying his creations as so horribly “other”? The prospect does make one nervous, though the series has so far stayed on a solid track, so it remains to be seen.

Providence #4 also manages to work in one of the most important themes in Lovecraft’s fiction — that of man’s inability to comprehend his own worthlessness in the grand scheme of the cosmos. Even when your cult is based entirely around that idea, individual humans have a pernicious way of assuming that they are the exception, that their lives matter, while others don’t. Hence, Providence says, we get sectarianism. Hence, we get bigotry, even among members of the same group.

At the end of the day, Providence #4 ends up being nowhere near as explosive as the previous issue. Its exploration of its themes is less in-your-face and damning, far more subdued and nuanced. While some of the cracks are starting to show in the concept, they have not yet crept into the execution, and this issue still makes for a solid, important entry in what may be the best indie title of 2015. If you’ve kept up so far, it’s not to be missed.