Writer – Alan Moore

Art – Jacen Burrows

Colors – Juan Rodriguez

Letters – Kurt Hathaway

Published by Avatar Press, Inc.

For a comic whose publisher regularly bills it as “the horror event of the year,” Providence has until this point been rather light on the scares. Sure, it’s had its close encounters. Black’s fascism-tinged prophetic dream in issue #3, for instance, stamps itself uncomfortably on your brain, but it’s not scary. There’s also the classic-style “monster go boo!” appearance of the demon Lillith in issue # 2, but anyone who’s ever read a similar moment in prose fiction or viewed one playing out on the cinema screen is likely to walk away more than a little underwhelmed. This can’t really be chalked up to the failure of its creators Alan Moore and Jacen Burrows, but is rather symptomatic of one of the major problems horror has in comics generally, and one of the major challenges comics have to overcome on the road to delivering actual scares.

It’s time to say something that might be a little controversial. As wonderful as the medium of graphic sequential storytelling is, its ability to create a real sense of fear in the audience is often limited. In prose fiction, a careful author can parse out the necessary details, adding just enough to create a sense of menace around the protagonists, but keeping back enough to maintain an ever-present sense of danger. Remember: it’s not what you see that’s scary, it’s what you don’t see. The same holds true for film and TV, except moving pictures are often obligated to fill in the gaps that would otherwise be the work of the audience’s imagination, and this usually has the effect of lessening the horror. However, a good filmmaker can use mise-en-scène, sound mixing, careful and deliberate pacing, and special effects to their advantage. The filmmaker may not have the same ability to get the audience to participate in their own scares, but they can do their best to make their monster believably terrifying, time the rhythm of their imagery for the maximum effect, and craft the noise, music, and tone for just the right amount of aural intensity.

Comics are at something of a disadvantage because they sit right in the middle of film and prose. Because of the need for images the audience takes in rather than creates for themselves, creators can’t just leave it up to the reader’s imagination. They have to draw out every horrible detail rather than letting them fill in the blanks. Taking print as a medium into account, the creator cannot force the reader on a relentless, merciless trudge through the horrors that unfold – the reader is free to linger on panels as long as they like, and move on only when they’re comfortable. Because soundtrack is non-existent, the mood of the reader’s aural environment cannot be a factor. You can dish out the most horrible, gruesome story in the world, but it’s still not going to be driven home that way if the reader is blasting some Tay Sway on their headphones to cover up the sound of the crying child next to them on the bus.

Now, this is all working under the assumption that the point of any given horror tale is to cause fear, which may not always be the case. For many horror fans, the horror genre is more about the iconography of fear rather than feeling itself (think of the work of Tim Burton). Horror comics tend to be in that boat — gruesome and violent, but not frightening. Even Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, and the other offerings from EC – which many consider the greatest horror comics ever published – are more about the fun of monster stories than the fear of monsters.

With all this in mind, it’s been hard to figure out what kind of emotional experience the creators intend to impart with Providence. H.P. Lovecraft created his mythos of Great Old Ones and Elder Gods to inject some new life into a genre whose monstrous usual suspects – ghosts, vampires, werewolves – had all played themselves out. Of course, given Lovecraft’s monumental influence over the past eighty years, these days Cthulhu falls in love with Mary Sues in parody paranormal romance novels, and kills Justin Bieber at Eric Cartman’s behest. Basically, Lovecraft’s own creations have gone the way of ghosts and vampires.

Perhaps we’re starting to get a firmer grasp in things in issue #5 when Robert Black arrives in Manchester (Moore’s and Burrows’s real-world stand in for Lovecraft’s Arkham) where he encounters a denser collection of Lovecraft-pastiche than ever before. Here, we jump right into “Herbert West: Re-Animator before crossing paths with The Thing on the Doorstep, and then we pay a visit to Dreams in the Witch House before encountering The Colour Out of Space. And as our literary paths cross and jumble, so do time, reality and dreams. A sense of malignancy – and, dare I say it, real fear – begins to grow around Robert Black. But where is this fear coming from?

Perhaps we’re starting to get a firmer grasp in things in issue #5 when Robert Black arrives in Manchester (Moore’s and Burrows’s real-world stand in for Lovecraft’s Arkham) where he encounters a denser collection of Lovecraft-pastiche than ever before. Here, we jump right into “Herbert West: Re-Animator before crossing paths with The Thing on the Doorstep, and then we pay a visit to Dreams in the Witch House before encountering The Colour Out of Space. And as our literary paths cross and jumble, so do time, reality and dreams. A sense of malignancy – and, dare I say it, real fear – begins to grow around Robert Black. But where is this fear coming from?

Given the way the first four issues played out, it would be natural to assume that it’s not from the people Black has been crossing paths with, as eldritch and off-kilter as they’ve tended to be. As monsters, they’re something that we horror fans have had to deal with before, so we’re certainly not afraid to deal with them again. But, aside from that, Moore and Burrows have treated all of them with respect and empathy. The interpretation has seemingly been that when Lovecraft wrote about monsters, he was actually writing about the experience of society’s privileged being encroached on by the “other” – a world where the white, heteronormative, cisgender, Christian male cannot escape the existence of people who aren’t like him, and can’t get the idea of their purity being tainted out of their head. Naturally, Moore and Burrows have treated Lovecraft’s creations as having been unfairly maligned, and give them a bit of humanity this time around. It’s made the past four issues of Providence rather moving and progressive – though not scary.

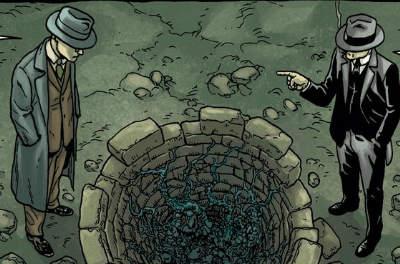

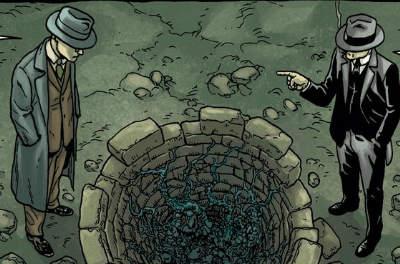

But there is a particular scene in issue #5 utilizing ideas from Dreams in the Witch House that manages to be the closest we’ve come yet. This isn’t because the image itself is all that gruesome (though Burrows’s artwork does a good job making it probably the most gruesome across all five issues), but because of the implications it has for the greater world of Providence. It’s become clear that the people we’ve come to empathize with over the past four issues may actually be up to no good after all. And perhaps that’s where the fear comes from: from the worry that we’ve been wrong about these people all along. Let’s not forget that there is some precedent for this: Providence is a prequel to Moore’s and Burrows’s other Lovecraft work Neonomicon, and if you recall in that story the occultists did not turn out to be the nicest people on the block – not by a long shot.

Providence #5 succeeds in creating fear the way other comic stories don’t because of how it has managed to cultivate empathy to this point. Our sense of trust is starting unravel at the same time as Robert Black’s. The presence of Mrs. Macey in Black’s dreams, the fact that something seems to be stalking him back and forth from dreams to reality, and the strange way Dr. Hector North acts around him signify the danger that Black is entrenched in. And if these branches off from the Stella Sapiente cult can be so dark and twisted, what about the Wheatleys? What about the people in Salem? This casts a new light on certain of the smaller, stranger, but not necessarily malignant moments we’ve encountered so far (the scene where Black first meets Tobit Boggs in issue #3, for instance, and the strange deal that seems to be going on in the back room of his refinery). Of course, the idea of revealing that “the other” has an unsavory, aggressive, downright violent side all along is a deeply problematic one, but perhaps that’s the point? Perhaps cultivating recognizably “bigoted” attitudes is the comic’s sneaky way of showing us the fearful side of humanity and ourselves – that it really is that easy to indulge in ignorance. The idea seems problematic in itself given its need to vilify the object of our prejudices (which is never actually the cause of real-life bigotry).

Moving forward, Providence seems to be moving down treacherous, uncharted paths where we’re not sure if we’ll meet friend or foe, but it remains as intriguing and engaging as it’s ever been.

Rating: 8.0/10